Remarkable Results of Experiments and Investigations Now Being Conducted in Large Hospitals for Mental Diseases and in Penal Institutions

An Interview with the Noted Musical Mental Expert

WILLEM VAN DE WALL

of the Department of Welfare of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

[Dr. Willem Van de Wall is one of the most unusual figures in present-day music. In the first place, his study of music was undertaken with the definite aim of determining its psychological and sociological value, and his whole life has been focused in this direction. He decided to study the harp so that he might play in different orchestras and in many different countries and thus view different individual types and different conditions. He was educated at the Hague, where he studied at the Royal Conservatory. He then studied the harp with the first harpist of the Gewandhaus orchestra In Leipsig. This was followed by many years’ service in foremost orchestras of Germany, Russia and the United States. For a time he joined a vaudeville “Banjo Quartet,” in order that he might see all parts of England. For seven years he was harpist of the Metropolitan Opera House Orchestra in New York and for one year he was with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Walter Damrosch. During the War he joined the Marines and was stationed in Washington where he became a part of the U. S. Marine Band, which regularly furnished music for functions at the White House. In 1910 he finally felt himself in a position to embark upon his chosen career as a specialist in the utilization of music in the direct treatment and prevention of mental diseases. His story of his work thus far is intensely interesting. His work has received the endorsement of medical specialists of highest standing, particularly because he has dogmatically striven to study and develop his methods under the guidance and with the coöperation of the leading psychologists of this country, recognizing their authority in the field of general mental medicines of which music is, according to his principles, an adjunct therapy. The committee for the study of music in institutions was organized in New York City to enable him to experiment along the lines of his endeavor. The success of his subsequent efforts caused the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to engage his services for the organization of musical activities on his principles in the various State institutions. At present Dr. Van do Wall is representing the State of Pennsylvania in a London Conference.

[Dr. Willem Van de Wall is one of the most unusual figures in present-day music. In the first place, his study of music was undertaken with the definite aim of determining its psychological and sociological value, and his whole life has been focused in this direction. He decided to study the harp so that he might play in different orchestras and in many different countries and thus view different individual types and different conditions. He was educated at the Hague, where he studied at the Royal Conservatory. He then studied the harp with the first harpist of the Gewandhaus orchestra In Leipsig. This was followed by many years’ service in foremost orchestras of Germany, Russia and the United States. For a time he joined a vaudeville “Banjo Quartet,” in order that he might see all parts of England. For seven years he was harpist of the Metropolitan Opera House Orchestra in New York and for one year he was with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Walter Damrosch. During the War he joined the Marines and was stationed in Washington where he became a part of the U. S. Marine Band, which regularly furnished music for functions at the White House. In 1910 he finally felt himself in a position to embark upon his chosen career as a specialist in the utilization of music in the direct treatment and prevention of mental diseases. His story of his work thus far is intensely interesting. His work has received the endorsement of medical specialists of highest standing, particularly because he has dogmatically striven to study and develop his methods under the guidance and with the coöperation of the leading psychologists of this country, recognizing their authority in the field of general mental medicines of which music is, according to his principles, an adjunct therapy. The committee for the study of music in institutions was organized in New York City to enable him to experiment along the lines of his endeavor. The success of his subsequent efforts caused the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to engage his services for the organization of musical activities on his principles in the various State institutions. At present Dr. Van do Wall is representing the State of Pennsylvania in a London Conference.

“IN MAKING any statement in connection with the utilization of music in connection with mental disorders it is necessary to employ the greatest scientific precautions. The whole subject is so vast that as yet only the thin frontiers have been explored. Physicians and penologists, besides institutional and governmental administrators, have made important steps at all times, and it has been my wonderful good fortune to have the benefit of the advice and cooperation of the finest minds in their field. Otherwise I would have great temerity in expressing any opinion at all.

“Some harm has been done to the right understanding of the value of music in mental treatment by self-advertising charlatans. The public is therefore warned against any exploitation of the thought that music is a panacea healing the highly complex disorders known as mental diseases in a cure-while-you-wait service by the conjuring strains of the fiddler’s bow.

“So astonishing are the few facts and experiences that have been obtained thus far, that it is not necessary to exaggerate the importance of this subject to gain interest and attention from the general public. The subject is so new, however, as an adjunct therapy in hospitals and prison management that unless the local officials have actually observed some of the results achieved, or else happen to be musical enthusiasts, there may be great difficulty at the start in gaining any recognition whatever. This may be illustrated by my first experience in this field. During my extensive travels over a great part of Europe and America in connection with my musical work, I met thousands and thousands of people and had made studies of different types. I also had literally read great numbers of books upon the individual and group, and, when an opportunity offered, had discussed the subjects with the best informed men and women. This was all necessary because the field was virgin. There were no colleges or universities where I might study the subject from the angle that interested me. It was necessary to map my own course and blaze the way.

“My first actual experience was at the Central Islip State Hospital, New York, an institution caring for six thousand patients. The Superintendent, Dr. G. A. Smith, is a music lover, and he organized in the early nineties one of the first hospital bands in the United States. This band was of unquestionable value to the institution. It was not a difficult task to gain Dr. Smith’s sincere interest in my vision, which was to utilize music first of all as a means of self-expression for patients, in addition to any entertainment value it may have. The patients were induced to make the music themselves in whatsoever form they pleased rather than to sit still and listen to musical offerings, although that type of diversion was by no means neglected. In such an enormous institution, however, it was also necessary for me to gain the confidence and coöperation of the heads of various departments in order to obtain the necessary coöperation. The most prominent of these was the clinical director, George Mills, now Medical Inspector for the New York State Hospital Commission. Here was a serious scientist, averse from any faddism, musical or otherwise, who had to be convinced by pure results and who became in time a genuine supporter.

“My first patients were possibly the most difficult cases to handle. They consisted of some sixty elderly women, patients of the chronic or prolonged type. Some had been in the hospital for decades. Many were considered unmanageable. The worker with mental diseases, however, must never consider a case hopeless. I know of one case of a man who was given up for twelve years. He more or less suddenly regained full control of his mental powers so that he was able to go back to society.

“In my first experiments I reached the individual by way of the group. The first step was to introduce a type of music which might possibly mean something to the audience. I sat at the piano and threw out several forms of bait. They were the folk-songs and the popular songs of the day and of some years ago, possibly representing the favorites of the youthful days of the patients. Immediately several patients came forward, joining in the singing, asking in turn for many others, starting to tell me about their life experiences and woes. This in itself is one of the most valuable products of music treatment; that is, it establishes a bond of confidence, and causes a patient to overcome his inhibitions and express himself about many things long harbored in his mind. Another type of reaction is the impulse of the patient to take part in the musical exercises. Here we achieve one of the most important gains; that is, that the patient who has turned himself away from the world, turns round about and joins again with his fellows on a plane of harmonious group expression.

“One patient in this group had wrapped herself in a blanket of old newspapers, passing her days by dozing on the floor. She had done this for years. She went to the piano, expressed her delight in the music and, when invited, played and sang, with some hesitation, the beautiful Celtic song, “Flow Gently, Sweet Afton.” This was the simple beginning of a change in her life. She is now of her own inclination leading the bed-time group singing in the ward. This is a most valuable work, creating a spirit of beauty and peace which continues even after the music has finished, causing a momentary happiness which ever gives to the life of those who have to spend the rest of their days in an institution, a rosy glimmer and a satisfaction like that enjoyed by someone who receives affectionate caresses. This woman, although not the type of a case in which a cure could be effected at her stage of advancement, developed so many new interests, also assisted by other forms of therapy by which she could thereafter be reached, that she discarded the paper-blanket stage of her existence and became a patient of greater usefulness and even of “bliss” in her environment.

“Of these prolonged cases, sixty patients, only a few left the hospital, about tweuty-five (sic) showed an active response, which manifested itself, preponderantly musical, by singing or playing, or, more physically, by dancing, and other similar manifestations. Approximately twenty-five others were usually interested but did not partake. A very small minority, only, did not show any apparent reaction.

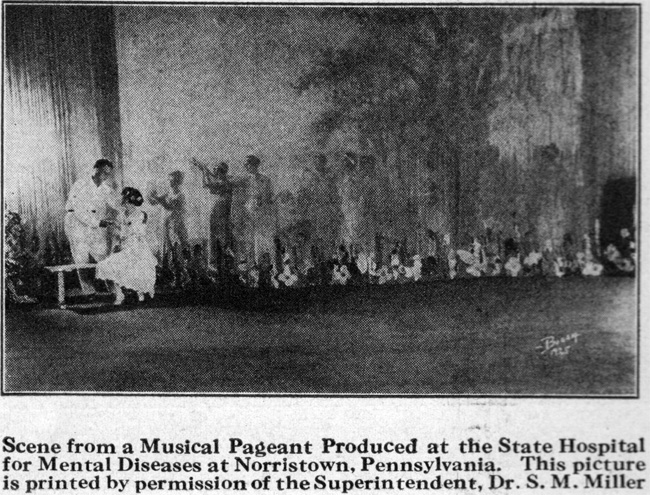

“However, the very encouraging results of this first experiment were such that at the Central Islip Hospital the work was continued and expanded, until at present, when some 1700 patients weekly, in regular sessions, according to a schedule, are undergoing a more highly developed form of musical exercise. This includes choral, choir, solo and community singing; band and orchestra playing; solo, aesthetic, social and stage dancing; musical calesthenics and musical dramatics.

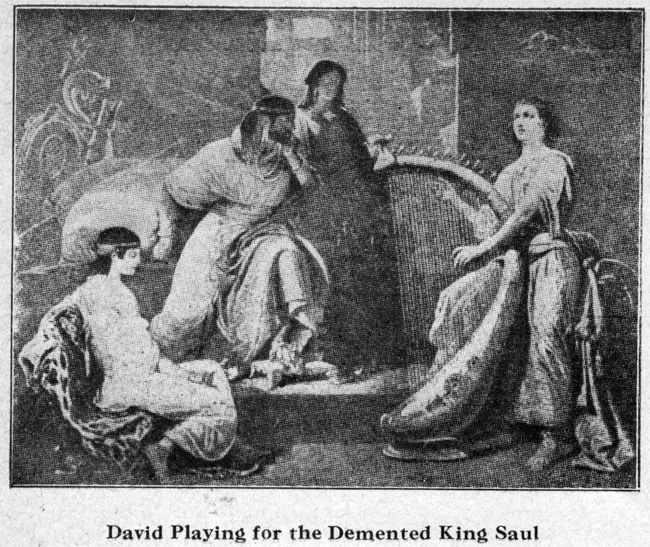

“Now what is there strictly original and new about this? In a certain respect, nothing at all. History offers many instances of cures resulting from the knowledge of the people of the therapeutic power of music. In the Bible, Samuel I, Chapter 17, we find that wonderful verse: ‘And it came to pass when the evil spirit from God was upon Saul, that David took an harp and played with his hand; so Saul was refreshed and was well, and the evil spirit departed from him.’ Jumping to the eighteenth century we have the wonderful case of the singer, Farinelli, who, in the year 1736, went to Madrid to sing for the melancholy King Phillip V. So resultful was his singing that the King recovered his mental health and rewarded Farinelli by an enormous annual salary of fifty thousand francs.

“Does it not seem a little astonishing that more has not been done to employ music more systematically with scientific intent to aid in the treatment and prevention of mental disorders? Whatever value or import my own activity may have, it seeks to give the practice of music a new value and a more intense significance by making it just like any other other form of therapy a part subject of the general medical arts and administration of the hospitals.

“Another important point to be mentioned, by which this type of musical application is characterized, is that it is used as a means to have the patient unburden himself; to lift him from passivity to activity; to revive the energies and sublime aspirations of his youth; finally, if possible, and desirable, in several cases, to develop his power of aesthetic self-expression. This means that the technical perfection of music practice has also its place in hospital music work. Right playing, right singing, correct interpretation, all of these things are therefore observed as closely as possible. Mental patients are keen of ten unsparing critics.

“For years mental patients have been played to, often by people who have an idea that anything, including their own musical antics, were good enough for the mental patient. When there was good music, it had some entertainment value, but the music made by the patients themselves is of far higher therapeutic value.

“Participants in the musical activities do so often figure among the numbers who are discharged from the hospital that the turnover of members of the patient band of Allentown State Hospital has eighty-five per cent. in one year. The presentation of hospital musical dramatic production has often to be repeated in a very short time, if at all, because of the discharge from the hospital of so many actors participating.

“Let me cite, for instance, a very striking case. One Italian boy was found by us as the inhabitant of a ward of very disturbed cases, liable at any time to make assaults. This boy begged to be permitted to partake in our exercise and rehearsals, promising to make good if he had the opportunity. He was a baritone, of a very boisterous character. First he was sent out under guard, but behaving extremely well, was paroled to the grounds; the more he sang the calmer he became, and when our production was over (six weeks after we found him in the place where the most dangerous cases are kept for safety) he left the hospital a free, self-controlled man, and seemingly has made good. This is a typical case.

“We have now worked out a plan by which the medical staff and the musical staff coöperate on a clinical basis, which has lifted the musical work from an amateur to professional standing, the musician coöperating with the other therapeutic departments of the hospital service.

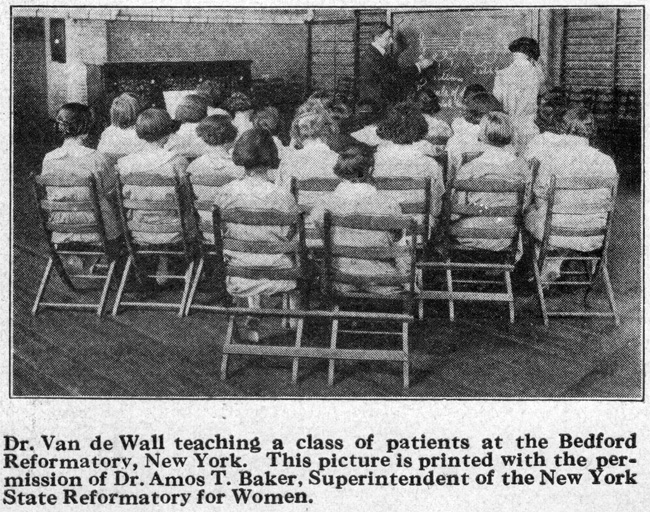

“There is also a great field for music in prison work. The modern penologist is inclined to look upon many criminal traits as symptoms, physical as well as mental defects and diseases. One stroll through the average

prison will easily confirm this. A progressive penologist, just like the progressive psychologist, welcomes any legitimate aid which will improve the physical, mental and moral condition of those confined in his care. Music does to a prison inmate what long talks and enforced discipline often fails to bring about; that is, the association of the prisoner with his fellow prisoners of his own free will in harmonious teamwork for a socialized goal of beauty.

“Music often produces instant improvements in behavior. On one of my regular visits to the Woman’s Work House, on Blackwell’s Island, the jail for New York City, I happened to come in just after a serious outbreak among the hardened type of women prisoners incarcerated there. I was advised for safety’s sake not to go near them. The bitter fate of the guards who had tried to reduce the wrath of these furious ladies caused this warning. Eager to give music the acid test, I regarded this as an opportunity and faced the group. The cells were opened and an excited, screaming, bawling mob surged into the room. Meeting them on the boiling emotional plane to which their seething anger had pitched them, I jumped upon the piano and ordered a colored prisoner to play for me. I started off as quickly as possible the strangest concert I ever led by shouting with all my strength, ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic.’ The mob gripped the suggestion and falling, in blind passion, in with any type of violent action, shouted and raved with me, taking over my tempo. This first number was followed by a gradual succession of calmer songs, intoned without an intermission of a second. The explosive rhythmical selections were systematically replaced by far more melodic and sedative tunes which I thought of as I went along. We wound up finally with such a song as ‘Hush-a-Bye, My Baby’ (The Missouri Waltz). By this time the mob had entirely exhausted its emotional energy and was consequently tired and satisfied. The mood from the furious had changed into one of pleased contentment. When the command came for them to go back to their cells they obeyed in orderly fashion without murmuring. They thanked me for the entertainment they had enjoyed, forgetting that they had entertained themselves and that this is as a rule the most satisfactory entertainment anyone may experience.

“In the work with male convicts in the big state penitentiaries as well as in the juvenile reformatories, musical activities have been shown to bring in an element of benevolent order and culture.

“A great number of prisoners are very anxious to be brought into contact with new thoughts and ideals, to feel finer emotions and to get rid of the darkness and filth which has so often clogged up their outlook on life and their actual careers. They welcome music as a message from another better, more hopeful, world.

“In surveying the work as accomplished thus far, there have been some very significant factors which seem to prove:

“1. That music can be utilized in systematic medical work to relieve mental suffering and improve institutional morale.

“2. That it is an inexpensive, practical and agreeable method welcomed by progressive authorities.

“3. That it is a technic which can be learned by adaptable persons.

“4. That the government authorities have already recognized and utilized it as a branch and a department of public service.

“5. That conservative Europe is now looking to the United States for further research which may make a vast difference in the lives of thousands who heretofore were considered doomed.

“The prospect is a most encouraging and inspiring one for the future.”