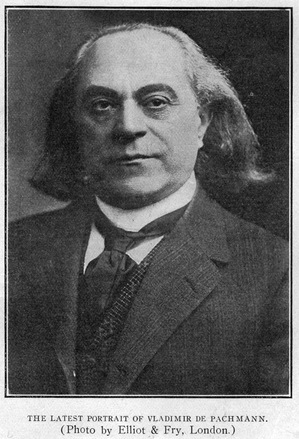

From an interview secured expressly for THE ETUDE with the distinguished virtuoso pianist VLADIMIR DE PACHMANN

[Editor’s Note.—The peculiar and inimitable gifts of M. Vladimir de Pachmann have attracted such unusual attention in all art-loving countries that it seems hardly necessary to give the biography of this well-known artist or to comment upon his playing.

[Editor’s Note.—The peculiar and inimitable gifts of M. Vladimir de Pachmann have attracted such unusual attention in all art-loving countries that it seems hardly necessary to give the biography of this well-known artist or to comment upon his playing. Born at Odessa, Russia, July 27, 1848, he was taught at first by his father, who was a musical enthusiast and a fine performer upon the violin. The elder de Pachmann was a professor of law at the University of Vienna and at first did not desire to have his son become anything more than a cultured amateur. Art, however, is always tyrannical, and when it points the way, the wishes of stern parents usually amount to nothing. De Pachmann is probably the best living example of a pianist who has been largely self-taught. His father gave him little more than paternal advice—never lessons in the generally accepted sense of the term. In 1866 he went to the Vienna conservatory to study with the then celebrated teacher, Joseph Dachs. Dachs was a concert pianist of the old and somewhat academic school. Academic perfection was his goal and he could not understand a pupil like de Pachmann, who apparently could not do things in the academic way. Dachs had been a pupil of Czerny and Sechter, and numbered among his pupils besides de Pachmann, Hans Schmitt, author of “The Pedals of the Pianoforte,” and Laura Rapoldi, who later gained a great European reputation.

The instruction of Dachs was rather amusing and irritating to de Pachmann, who chose to get results in his own individual way. Nevertheless, he made a very successful concert tour in Russia in 1869, and since then has toured the musical countries of the world many times. When de Pachmann toured Russia, Paderewski was only ten years old and many of the celebrated pianists of our day were not yet born. Naturally a philosopher and keen observer, this long experience has given de Pachmann a wealth of information which makes the following interview very valuable.

One of the most notable characteristics of de Pachmann is that he has never ceased to work, never ceased to practice with the view of making himself a better and greater pianist. He has not appeared in public in America for some years.

Recent London criticisms declare that he has made an entirely new pianist of himself, and that, while he has preserved all of the velvety touch of other days, he has developed a Bravura style which has not been approached since the days of Franz Liszt. De Pachmann, like many virtuosos, is a fluent linguist, being equally at home in many languages. The interviewer has tried to keep something of the polyglot flavor of this interesting educational conference.]

THE MEANING OF ORIGINALITY.

“Originality in pianoforte playing, what does it really mean? Nothing more than the interpretation of one’s real self instead of the artificial self which traditions, mistaken advisors and our own natural sense of mimicry impose upon us. Seek for originality and it is gone like a gossamer shining in the morning grass. Originality is in one’s self. It is the true voice of the heart. I would enjoin students to listen to their own inner voices. I do not desire to deprecate teachers, but I think that many teachers are in error when they fail to encourage their pupils to form their own opinions.

“I have always sought the individual in myself. When I have found him I play at my best I try to do everything in my own individual way. I work for months to invent, contrive or design new fingerings— not so much for simplicity, but to enable me to manipulate the keys so that I may express the musical thought as it seems to me it ought to be expressed. See my hand, my fingers—the flesh as soft as that of a child, yet covering muscles of steel. They are thus because I have worked from childhood to make them thus.

“The trouble with most pupils in studying a piece is that when they seek individuality and originality they go about it in the wrong way, and the result is a studied, stiff, hard performance. Let them listen to the voice, I say; to the inner voice, the voice which is speaking every moment of the day, but to which so many shut the ears of their soul.

Franz Liszt—ah, you see I bow when I mention the name—you never heard Franz Liszt? Ah, it was the great Liszt who listened—listened to his inner voice. They said he was inspired. He was simply listening to himself.

MACHINE TEACHING.

“Nun, passen Sie mat auf! I abominate machine teaching. A certain amount of it may be necessary, but I hate it. It seems so brutal—so inartistic. Instead of leading the pupil to seek results for himself, they lay down laws and see that these laws are obeyed, like gendarmes. It is possible, of course by means of systematic training, to educate a boy so that he could play a concerto which he could not possibly comprehend intelligently until he became at least twenty years older; but please tell, what is the use of such a training? Is it artistic? Is it musical? Would it not be better to train him to play a piece which he could comprehend and which he could express in his own way?

“Of course I am not speaking now of the boy Mozarts, the boy Liszts or other freaks of nature, but of the children who by machine-made methods are made to do things which nature never intended that they should do. This forcing method to which some conservatories seem addicted remind one of those men who in bygone ages made a specialty of disfiguring the forms and faces of children, to make dwarfs, jesters and freaks out of them. Bah!

ORIGINALITY THE ROAD TO PERMANENT FAME.

“Originality in interpretation is of course no more important than originality in creation. See how the composers who have been the most original have been the ones who have laid the surest foundation for permanent fame. Here again true originality has been merely the highest form of self-expression. Non e ver? When the composer has sought originality and contrived to get it by purposely taking out-of-the-way methods, what has he produced? Nothing but a horrible sham—a structure of cards which is destroyed by the next wind of fashion.

“Other composers write for all time. They are original because they listen to the little inner voice, the true source of originality. It is the same in architecture. Styles in architecture are evolved, not created, and whenever the architect has striven for bizarre effects he builds for one decade only. The architects who build for all time are different and yet how unlike, how individual, how original is the work of one great architect from that of another.

THE MOST ORIGINAL COMPOSERS.

“The most original of all composers, at least as they appear to me, is Johann Sebastian Bach. Perhaps this is because he is the most sincere. Next I would class Beethoven, that great mountain peak to whose heights so few ever soar. Then would come in order Liszt, Brahms, Schumann, Chopin, Weber and Mendelssohn. Schumann more original than Chopin? Yes, at least so it seems to me. That is, there is something more distinctive, something more indicative of a great individuality speaking a new language.

“Compare these men with composers of the order of Abt, Steibelt, Thalberg and Donizetti, and you will see at once what I mean about originality being the basis of permanent art. For over twenty years my great fondness for mineralogy and for gems led me to neglect in a measure the development of the higher works of these composers, but I have realized my error and have been working enormously for years to attain the technic which their works demand. Some years ago I felt that technical development must cease at a certain age. This is all idiocy. I feel that I have now many times the technic I have ever, had before and I have acquired it all in recent years.

SELF-HELP THE SECRET OF MANY SUCCESSES.

“No one could possibly believe more in self-help than I. The student who goes to a teacher and imagines that the teacher will cast some magic spell about him which will make him a musician without working, has an unpleasant surprise in store for him. When I was eighteen I went to Dachs at the Vienna Conservatory. He bade me play something. I played the Rigoletto paraphrase of Liszt. Dachs commented favorably upon my touch but assured me that I was very much upon the wrong track and that I should study the Woltemperirtes Clavier of Bach. He assured me that no musical education could be considered complete without art intimate acquaintance with the Bach fugues, which of course was most excellent advice.

“Consequently I secured a copy of the fugues and commenced work upon them. Dachs had told me to prepare the first prelude and fugue for the following lesson. But Dachs was not acquainted with my methods of study. He did not know that I had mastered the art of concentration so that I could obliterate every suggestion of any other thought from my mind except that upon which I was working. He had no estimate of my youthful zeal and intensity. He did not know that I could not be satisfied unless I spent the entire day working with all my artistic might and main. Soon I saw the wonderful design of the great master of Eisenach. The architecture of the fugues became plainer and plainer. Each subject became a friend and each answer likewise. It was a great joy to observe with what marvelous craftsmanship he had built up the wonderful structures. I could not stop when I had memorized the first fugue, so I went to the next and the next and the next.

A SURPRISED TEACHER.

“At the following lesson I went with my book under my arm. I requested him to name a fugue. He did, and I placed the closed book on the rack before me. After I had finished playing he was dumfounded. He said, ‘You come to me to take lessons. You already know the great fugues and I have taught you nothing.’ Thinking that I would find Chopin more difficult to memorize, he suggested that I learn two of the etudes. I came at the following lesson with the entire twenty-four memorized. Who could withstand the alluring charm of the Chopin etudes? Who could resist the temptation to learn them all when they are once commenced ?

“An actor learns page after page in a few days, and why should the musician go stumbling along for months in his endeavor to learn something which he could master in a few hours with the proper interest and the burning concentration without which all music study is a farce?

“It was thus during my entire course with Dachs. He would suggest the work and I would go off by myself and learn it. I had practically no method. Each page demanded a different method. Each page presented entirely new and different technical ideas.”

(The second section of Mr. de Pachmann’s article will be presented in the November Etude.)