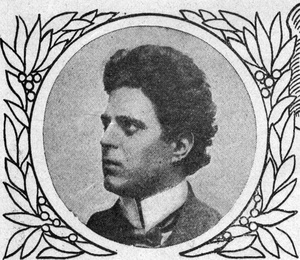

TOLD BY THE COMPOSER.

[Editor’s Note.—Few of the younger composers of today have had such a light for recognition as had Mascagni. The extremely dramatic manner in which he tells his own tale has induced us to secure permission from the “Sunday Magazine” to publish the following article.]

When one has arrived in art or worldly affairs, it is possible to look back without regret upon the hardships of the years of apprenticeship that paved the way to success. Time softens the memory of want and struggle, the poignancy of wrecked ambitions, and we get the true perspective of our lives and a realization of the values of our failures as well as of our achievements. How flat and uninteresting would be the retrospect, if there were no shadows to bring out the high lights!

When one has arrived in art or worldly affairs, it is possible to look back without regret upon the hardships of the years of apprenticeship that paved the way to success. Time softens the memory of want and struggle, the poignancy of wrecked ambitions, and we get the true perspective of our lives and a realization of the values of our failures as well as of our achievements. How flat and uninteresting would be the retrospect, if there were no shadows to bring out the high lights!The true musician is never a misanthrope. Cost what it will, he remains steadfast in the love and devotion for his art. And when, perchance, he drinks the inspiring draft of success, the memory of past defeats and struggles leaves no bitterness in the cup.

Why hunger and hardship and adversity clung to me, through the days of my apprenticeship, I have never questioned Providence. Whatever happened was part of human experience. It is over now; but it has left its lesson. All my present disappointments are lessened in view of those which are past. We can look forward with serenity when we realize that Fate has dealt us its hardest blows. For that reason I keep ever fresh the memory of my youth. Perhaps some young musician, struggling as I did, may find in the recital some sustaining hope.

Music was always the consuming passion of my life. The clearest recollection of my infancy is the keen delight I felt when I could steal to the piano and touch it softly, so that none could overhear. I longed for the day to come when I should be old enough to take lessons and be free to practice as long as I pleased. When that day did come, healthy and boisterous youngster as I was and fond of all childish sports, I found my greatest delight at the instrument. Even in those days my ambition was to create rather than to be a virtuoso. When I was ten I struggled for weeks over my first serious effort at composition, a setting for three voices of the “Kyrie Eleison” of the mass service. Of course it was my childish ambition to write an entire mass; but my teacher advised me to wait. After I had struggled awhile with the “Gloria,” I decided to take his advice.

In my eighteenth year I left my home in Leghorn to enter the Conservatory of Milan and begin the serious study of composition. What would I not give to be able to feel once more the furious enthusiasm of that year! The Universal Exposition of 1881 was then in progress at Milan, and I composed a setting of the “Paternoster” and “Ave Maria” for the prize competition, and was rewarded with honorable mention. Among my other compositions that winter were a musical setting to Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” and a little two-act opera, “La Filanda,” which I had the honor of dedicating to Ponchielli, the composer of “Gioconda.”

An inspiration that obsessed me for years came during my second year at the conservatory. Maffei’s translation of Heine’s “William Ratcliff” fell into my hands. The drama took such a hold on me that Maffei’s verses were indelibly fixed in my memory. I recited them day by day and at night I dreamed of Ratcliff’s fantastic passion. During the winter I composed three scenes of the opera; but in the following summer, while at home in Leghorn, I cast aside most of the music of the “Love Duet” and did not complete it to my own satisfaction until my return to the conservatory the following season.

During my third year I began to yield to the promptings of youthful conceit. We were an enthusiastic lot of youngsters, frankly in love with our art and our own abilities, and much given to proclaiming how we were going to startle the world.

CONDUCTOR AT ONE DOLLAR A DAY.

Just at this time the opportunity came to act as substitute conductor with a little opera company which was being organized for a brief season at Cremona. I jumped at the chance, and without a regret left the good professors who had been so kind and encouraging to me. The impresario of our company was a good-natured chap named Forli. He agreed to pay me the munificent sum of five lire (one dollar) a day. I will say for him that he fulfilled his contract honorably, although circumstances over which he had no control made salary day a movable feast in our company.

As I was only the substitute conductor, my chance to wield the baton was dependent on the state of the regular conductor’s health. The rascal was never out of sorts and lived with irritating regularity. I did not wish him harm; but many times, I fear, I gave way to the hope that a sudden cold might put him to bed for a few days, so that I might have opportunity to conduct the orchestra. The coveted honor finally came to me at Parma, where I directed a performance of Lecoq’s “Heart and Hand.”

From Parma we went to the Teatro Brunetti at Bologna, where business went from bad to worse. Finally, one rainy day, the good-natured Forli abandoned hope, and we were told we might take a walk. I could scrape together only enough money for my railroad fare to Leghorn, and, packing my few belongings, returned home from my first adventure like a whipped dog.

JOYFUL NEWS FROM NAPLES.

Summer and fall passed in idleness and dejection, and then came the joyful news that Forli had reorganized his company for a season at the Teatro del Fondo in Naples and wanted me for director. I rushed to Naples, accepted his beggarly terms with gratitude, and was in the seventh heaven of delight at finding myself addressed as “Maestro” on every side.

The life of an opera conductor in Naples is never without excitement. I recall one Sunday afternoon when we were giving the little opera “Satanella.” The theatre was full as an egg and noisy as a Neapolitan theatre always is. The “No Encore” rule is a sure incentive to riot there; but I was trying to save the company, as we were due for another performance at night. For some time I staved off any interruption; but after one number the cries of “Bis!” shook the house. I remained firm, despite the howling and hissing, until there was a sound of ripping furniture in the gallery and a large object sailed out into space and was describing a nice sharp curve that would have ended exactly on the back of my head. I dodged just in time to bow to the audience and yield to its pleasure.

Forli’s season ended disastrously; but Sconamiglio immediately reorganized the company and engaged me as director at an advance of salary. I received seven lire (one dollar and forty cents) a day. The little company was excellent, and we enjoyed both financial and artistic success. I was very proud and happy, especially when the proprietor of the Politeama of Genoa came to Naples and engaged us for ninety performances, including the carnival season of 1885.

After Genoa, the company took to the road, going first to Alexandria, thence to Modena, from there to Ancona, and finally wound up at Ascoli, where a fête incidental to the inauguration of a street railway was in progress. We had one good audience there, and no more. Much as I regretted the dissolution of the company, I was not altogether sorry our wanderings were done. The excitement and hardships of travel were bad enough; but worse was the

expense of living on the road. With my meagre income I was always out of pocket, and when we were in Ascoli I was without a penny.

If there is a Providence the world over for drinkers, surely there is in Italy a special Providence for musicians. I found sympathetic friends in Ascoli, who saved me from downright starvation, and when I played for them what I had already written of my opera “Ratcliff,” their kindness was increased and I was proffered help so that I might push the opera to completion.

My patrons, however, were far from prosperous, and what little help they generously gave was not enough to keep me from experiencing the pangs of unsatisfied appetite. I tried to obliterate the consciousness of an empty stomach by feverish devotion to work. The physical pangs of hunger I might have endured; but the mental effects overcame me. I began to “see things,” as you say, and found myself in the same predicament as my hero Ratcliff, who, you may recall, had two phantoms always before him. All the time I was writing letters for help, here, there, everywhere, not remembering the moment a letter was posted whither it was sent or to whom I had addressed it.

My entire worldly possessions at the time were a gold ring and a silver watch and chain. I sold them in desperation and squandered two lire on a square meal, consumed it slowly to get the full benefit out of every mouthful, and topped it off with the added extravagance of a cigar.

Before my money ran out again I received an invitation from Duke Cirella to join a company he was organizing in Naples. A money order for twenty dollars accompanied the offer and made its acceptance possible. We played a month at the Teatro del Fondo before the Duke’s venture came to grief.

For six weeks I was without work; but not idle. I worked incessantly on the scoring of my opera, and the bundle of musical sheets in my valise grew rapidly. It was there I kept my treasured work when I was not toiling over it, and all through my travels I guarded that valise as carefully as though it was filled with money and jewels. If my meals at this period were not regular, my diet at least was steady. I could afford nothing but macaroni, and I tasted nothing else for weeks. I was able thus to avoid the discomfort of hunger, and kept my spirits fresh by long rambles along the coast to Posilipo and Portici. I would walk for miles dreaming with eyes wide open, weaving fantastic visions of future fame and glory.

Once more an impresario tempted fate at the Teatro del Fondo and I was engaged by Maresca as director of the company. We played a short season with some success, and then began our wanderings, which brought us finally to Cerignola. where we remained throughout the carnival of 1886. My salary was now ten lire (two dollars) a day, and it proved sufficient for the needs of my wife and myself. But the weariness of the wandering life, the nonsensical gossip and multitudinous jealousies in an aggregation of artistic temperaments, and the ever-present specter of adverse fortune had dulled the edge of my ambition to be known as a great operatic conductor.

WOULDN’T LEAVE HIS FRIENDS.

In Cerignola I made many warm friends, beginning with the Mayor, and when I opened my mind to them they encouraged me to leave the company and remain among them as a piano teacher. I played the instrument discreetly, and knew that Nature had endowed me with the capacity for teaching. So my resolution was formed.

My heart glows when I recall the years I spent in Cerignola. I had youth and strength, and burning ambition for work. Even if the piano lessons were scarce during the first months and we had to achieve marvels of economy to keep the pot boiling, we lived amid kindness and encouragement.

My good friend the Mayor and other gentlemen of the city saw after a few months that the hopes they had held out in persuading me to remain among them were not being fulfilled. Finally they came to a heroic resolution and prevailed upon the council to establish for my benefit the unheard-of position of director of a school of orchestra, at a salary of twenty dollars a month.

The issue remained to be faced, and I approached it with strategy. When the pupils came, I explained that the basis of all orchestral knowledge was theory, and began to instruct them accordingly in a field with which I was thoroughly familiar. We had nothing but theory for six months. Meanwhile the various instruments were kept at the school, where they were at my disposal. Hour after hour I spent there in practice, with the doors locked. It was not so pleasant, I recall, when the weather was hot, and I had to keep the windows securely closed while I struggled with the loud-sounding brass instruments. Finally, after untiring practice, I mastered them all, strings, wood, winds and brass. When I was able to perform on everything, from the contra bass to the harp, the practical instruction began. As I look back now on the work of those first six months I cannot but feel that I earned every penny of the twenty dollars a month allowed by the city.

Meanwhile my pupils advanced famously. I had some piano pupils outside the conservatory, and twice a week went to the neighboring city of Canossa to drill the Philharmonic Society of that place. What spare time I could find I devoted to the score of “Ratcliff.” After two years and a half I had it fairly complete; but not as I wanted it. However, I laid it aside, and have never touched it since.

The notion had come to me that it might be easier to impress the public with a work of more popular appeal and of less ambitious construction. For several years the main idea of “Cavalleria Rusticana” had been in my head, and now I decided to take some steps toward working it out. When Novi Lena, Deputy for Leghorn, died in 1888, I availed myself of the reduced railroad rates granted to electors and returned to my birthplace to request my great friend Tergione to compose a libretto for me. He was not enthusiastic, and I returned to Cerignola very heavy hearted. Professor Michele Sinischalchi then tried to persuade his friend Master Rocco Pagliara to furnish my libretto; but Pagliara felt he could not give up the time to the work without some positive assurance of compensation. He offered to do so if I could find a publisher to buy “Ratcliff.”

Just at this time the publisher, Edward Sonzogno, offered his great prize for an operatic competition. To win it meant not only relief from poverty, but the performance of my work by the best artists, and therefore the fullest opportunity to show what talent I possessed. I was frantic for a libretto, and railed at my lack of money to procure one. Finally, after I had bombarded my friends in Leghorn with letters begging them to induce Tergione to help me, I was overjoyed by receiving solemn assurance that I should have the libretto for “Cavalleria.”

A FAMOUS ALARM CLOCK.

Then, indeed, I began to dream in real earnest. My head was full of the music of the various scenes as I had conceived them. And all the time buzzing in my ears were the words, “They have murdered Neighbor Turridu!” I wanted a big effect for that scene to close the work with a strong dramatic impression.

One morning as I walked the main street of Canossa on my way to a lesson, the finale burst upon me, swift and vivid as a lightning stroke. I could hear those words, not sung, but shouted with surprise and horror, which was echoed by a crashing theme in the orchestra as Santuzza reeled on the stage and brought the work to a close with her despairing cry for her dead lover. The whole scene was clear before me, and it went into the opera without alteration. I can say, therefore, that the end of the opera was its beginning.

When I received by mail a few days later the first verses of the libretto (it was the “Siciliana;” for the prelude was an afterthought), I was very happy, and in a joking mood said to my wife:

“We have a great expense to meet.”

“What is it?” she asked with anxiety.

“We must buy an alarm clock.’,

“And for what?”

“To-morrow I must rise before daybreak and begin to write ‘Cavalleria Rusticana.’ “

That ended all possibility of protest, and, with reckless disregard of our scanty financial hoard, we went out joyfully together to make the big purchase. I remember to this day that our shopping expedition resulted in the extravagant outlay of nine lire.

I set the alarm, and we retired early. But our purchase proved an unnecessary luxury, after all; for during the night, February 3, 1889, our little angel Mimi was born. In spite of that I kept my promise to myself, and day was just breaking when with a heart full of joy and gratitude I began to write the opening chorus of the opera that soon after brought me fortune and fame.