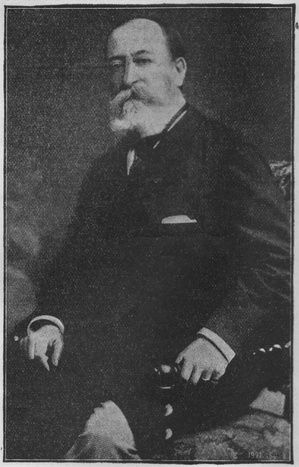

BY ISIDOR PHILIPP.

(Translated for The Etude.)

Saint-Saëns was an infant prodigy. One of the biographies of Saint-Saëns reads as follows:

“In 1846 his mother gathered together in her drawing-room some amateurs to hear her son play. Stamaty, who was his teacher, played with him, as a duet, a Mozart sonata, and accompanied him in two concertos, by Hummel and Beethoven. Saint-Saëns also played several of Bach’s fugues. He did so well that he at once made his début at Pleyel’s. He charmed everyone with his facility of technic, his force, color and expression.”

Success followed immediately. In compositions of the most different styles his comprehension of the works was always equal to his facility in playing them.

Such was Saint-Saëns in his youth, such he is today. Listen to him play Beethoven’s E flat concerto. Is it possible to play it more nobly, with a more true and profound sentiment? The suppleness and sureness of this great artist of seventy years is so astonishing that in listening one does not experience the inquietude usual in hearing difficult compositions. The expression is always within the limits of the purest taste. There is no pounding in his technic; his articulation is simple, his arm free, the touch attacked with such miraculous skill, that

Such was Saint-Saëns in his youth, such he is today. Listen to him play Beethoven’s E flat concerto. Is it possible to play it more nobly, with a more true and profound sentiment? The suppleness and sureness of this great artist of seventy years is so astonishing that in listening one does not experience the inquietude usual in hearing difficult compositions. The expression is always within the limits of the purest taste. There is no pounding in his technic; his articulation is simple, his arm free, the touch attacked with such miraculous skill, that

Saint-Saëns produces a most beautiful legato, such as our modern players do not seem to desire. Under his fingers the piano is transformed. He has the secret of the timbre of the orchestra, the charm and persuasive accent of the voice.

His precision, rhythm, the nimbleness of his fingers, the brightness of tone, the art of modulating and shading infinite sound, the assimilation of the playing with the sentiment of the composition, is so perfect that it seems that the interpreter is also the creator. These are the distinct qualities of the marvelous virtuoso.

Gifted with a prodigious memory, Saint-Saëns was the evocateur of Bach, the truthful interpreter of Mozärt and Beethoven, the fiery and spiritual translator of Liszt. He reproduced the fugues of Bach by reconstructing their powerful architecture; he gives to Mozärt a grace and freshness, he reveals the depth of Beethoven, he captivates with an inconceivable audacity the traits of bravoure with which Liszt enriched pianoforte literature, and plays his own works, no less original than those of Liszt.

Saint-Saëns’ work for the piano is extensive. He has touched all kinds, and in many proved himself superior to his predecessors.

His five concertos, “Africa, la Rapsodie d’Auvergne,” under different titles, are the most interesting for piano and orchestra. The first concerto (Op. 17) is charming and brilliant. But what a leap from the first to the second (Op. 22). What originality, what life, what force, what brightness, what color in that work, which has good reason to be the most-played piece of the time. The three passages of the concerto in E flat and the fourth in C minor shine forth in their grandeur and power with the same qualities as the second. The fifth, original, colored, spiritual, in the second part, a Moorish rhapsodie of delicate poesy in the first passage; of a virtuosity so wonderful in the finale, will become the rival of the second in the favor of virtuosos.

The etudes Op. 52 and 111 are small masterpieces of invention. Each page contains ingenious findings in technic or sound. His transcriptions from Bach, Haydn, Gluck, Beethoven (finale of the Ninth Quatuor, the chorus of Dervishes), of Gounod or Bizet (“Scherzo of the Pecheurs de Perles”), as interesting as those of Liszt or Alkan, retain their original poesy and power. The shortest pieces, waltzes or mazurkas the suite (Op. 90) “Isamäilia,” “Romance.” are in turn of a tender and delicate sentiment, colored or powerful, but always of the finest type.

Saint-Saëns has also written a series of works for two pianos, which are variations upon a theme of Beethoven, the spiritual “Scherzo,” the “Caprice Arabe,” the “Polonaise Heroique.”

Saint-Saëns is an incomparable organ virtuoso, and by a prodigious science produces effects in color. You should hear him play a paraphrase of Liszt on the choral from the “Prophet.” His improvisations are charming, poetic, spontaneous, tender. His works for the organ, however, are few; the “Rhapsodies Bretonnes” (Op. 7) are the chief.