Toward the end of a season, late in the eighties, the rumor got abroad that one of the greatest pianists and teachers of the time would come to Berlin and teach an artist class in one of the great conservatories there during the month of May. This master was none other than Dr. Hans Guido von Bülow, and the institute” which hoped to have the honor of a pedagogical visit from him was the Klindworth Conservatory, founded by Karl Klindworth, whose name is known in America chiefly through his editing of the complete works of Chopin and the sonatas of Beethoven. The two men were close friends, which is proved by the fact that Bülow was ready to recommend and use the Klindworth edition of Beethoven when he himself had edited many of the sonatas. Another proof is that the great pianist at the request of the Director was willing to leave his work in Frankfort a/m Main, where he was then living, and come to Berlin, to shed, for a short space, the lustre of his name and fame upon the Klindworth Conservatory, the youngest of the many institutes of that music-saturated city.

It was a bright May morning when he entered the music room with the Director.

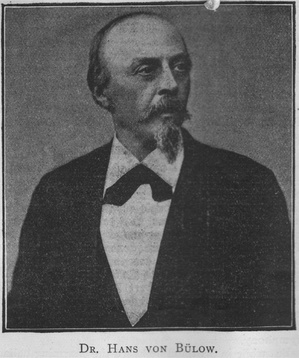

The Director introduced the Master, who stood there bowing; a small man with a large intellectual head and piercing dark eyes, hidden behind glasses.

Every movement was quick and alert, and exceedingly bright and wide-awake mentality. He bowed to the class, saying he was glad to see so many Heissig (industrious) students.

It had been announced that only compositions by Brahms, Mendelssohn, Raff and Liszt would be heard at these lessons, and on this first day all these composers were drawn upon to furnish forth the repast.

The great master was in amiable mood and made constant and witty comment on music and musicians, and especially on the compositions under consideration. His memory was prodigious. Not a piece for piano could be mentioned that he did not know. He played with and for the pupils and was always alert and on the qui vive. When he played a passage he made its meaning so clear, so forcible that the listener was convinced of two things: That it was the only way it should be played, and secondly, that anyone might do it so. That is always the virtue of clarity—to make difficult things seem easy. He analyzed everything down to the minutest detail. It was keen, clear, intellectual playing, of the head rather than of the heart. What of that? Such a teacher will illustrate the form and content of a composition more clearly than one who thinks first and always of the emotional side. “Clearness, clearness, clearness,” he would reiterate, “that is the first thing—(Deutlichkeit is das Erste). Every line, every measure must be thoroughly analyzed for touch, tone, content and expression.”

In scale playing, von Bülow used a slanting position of the hand, with fingers and thumb well curved.

AN EXERCISE FOR SMALL HANDS.

As he had very small hands he had used special and original means to increase their span. One of these was an exercise in skips of broken tenths. He recommended their practice with each hand alone at first, beginning with the lower note and going up and down the keyboard in a scale of tenths—and then repeating, beginning with the upper note. After this can be done smoothly, take the hands together, in parallel motion. A more difficult form of the exercise is in contrary motion, beginning in the center of the keyboard with thumbs on middle C, and playing the skips for one and two octaves each way, always returning to the center. These broken tenths should be practiced in all keys, and their faithful study would make every form of skip, in pieces, easy.

The master spoke rapidly, in a quick, nervous fashion, and in a mixture of German and English. The keynote of his remarks was a plea for clearness of utterance on the piano. He used to say “Let us have music speaking rather than music chattering (musik sprechen gegen musik plappern). We must make the piano speak. Music is a language. As in speaking we use a separate movement of the lips, so in certain kinds of legato the hand should be taken

up after each note. What one cannot speak or sing in one breath, one cannot play in one breath. Pauses, too, have great value in bringing out the thought of a composition.”

“It is difficult to play passages where two notes alternate with three notes. In preparation for such passages, scales may be practiced in this way.

Or in this:

“We must make things sound well, agreeably, in a way to be admired. When we find a seemingly discordant passage, then try to get the most out of it. Practice a dissonant chord so that it sounds well in spite of its sharpness. Think of the instruments of the orchestra, their different qualities of tone and try to imitate them on the piano. So, play with variety of tone (also bitte, coloriren!). Think of every octave as having a different color.”

“When octaves are played in not too rapid tempo, the first and fifth fingers are always used. The hand is held in a concave position well arched, and the wrist action is free and supple.”

“The first time one hears a new work there is so much for the mind to grasp all at once that there is not much pleasure. The second time it is easier to understand, and when one has heard it twelve times the pleasure is complete. This applies to the best in music. Therefore when we play, we must constantly consider the listener, and put the piece in the best light. Sing the themes, make the sharp discords milder.”

The Brahms variations on a theme of Handel were played at this lesson, also shorter pieces by Brahms and Liszt. Every work was illuminated by the keen intelligence of the master. The set of variations is a scholarly and beautiful work which deserves to be studied by every pianist and teacher.