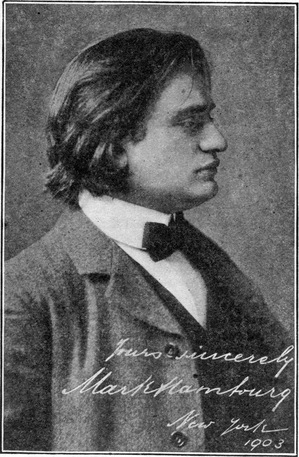

And Revised for Publication by

MARK HAMBOURG

The question has often been put to me, Should a boy who shows no especial musical talent be made to study the piano?

There are two ways of looking at the matter. The refining influence of music, and its aid in developing the mind is sufficiently recognized to need no further debate just now.

On the other hand, to persist in making a boy continue his musical studies after a fair trial has proven that he has neither taste nor talent, is at once serious and absurd. The time that he wastes under such conditions might have made telling effect if devoted to another branch; and that is a loss of far greater consideration than the money expended. But the fact that many thousands are thus annually wasted, is in itself a grave enough question.

What is a fair trial? is the consequent question. To my way of thinking, the main trouble often lies with the teacher. If he fail to interest a boy in his music the outcome is a foregone conclusion; and too often he does not interest him.

The mere fact that a boy tries to get out of practicing is no indication that he lacks talent. In my own early experience, I went so far as to run splinters into my fingers to escape this ordeal; and it was some little time before my father discovered that these repeated accidents were due to other than unforeseen causes.

At eight years of age things that amuse us appear very ludicrous at forty-eight. It was Talleyrand who said to a man confessing that he did not know how to play whist, “What a lonely old age you are preparing for yourself!” I would apply the same thing to a man totally ignorant of music.

Not long ago I heard a boy play whom I had not heard for some time. “What is the matter with your playing?” I asked, “it is so rough.” I found out that he had been going in zealously for football during his holidays. Not that I decry games, for I am an enthusiast in that direction. But it would be no more sensible to decry what music does for the mind than what games do for the body.

To give the boy a fair trial in music you must make the study of it interesting. Let him play melodies; explain chords and the relation of notes to him; do not make him practice more than half an hour at a time—and never let him practice alone.

The beginnings in music are along far better lines now than they were in the past, and the mind is more properly considered. It is no longer the difficult thing to start that it used to be.

Again, too many parents start a boy in the study of music too early. He should never begin before eight, and to disgust him with it then by going about it the wrong way, settles the matter for good and all. And to be disgusted with anything at eight is rather lamentable, is it not?

Some boys have greater aptitude for music, others less. If they go at it willingly, so much the better; if unwillingly, try to find out the true cause. The mere matter of endeavoring to escape practice is no standard to gauge by. If a boy wants to find a way out of that, he will generally manage to find it. I remember my own powers of invention in this direction too well to doubt it.

To persist in keeping a boy at the piano when it has been fairly demonstrated that he has no talent, will plant such a loathing in his mind for the “soothing” art that his entire lifetime will be too short to get over it. It is this persistence after a fair trial that does the harm, for harm it assuredly is, meaning, as it does, the forcible robbing of time that might have been worth much to him in later life had it been turned in some other direction.

Every boy, with small exception, has a talent for something. That talent, if properly cultivated, will not unlikely influence his entire future. If for drawing, for instance, his career may be that of a successful architect or inventor, and so on through the list. It is the little things in life that turn the course of it, and prove the most powerful of influences.

The world has an unfortunately large percentage of those whom we deem unsuccessful men. How many of these would have been unsuccessful if the proper talent had been considered and given even a start in its cultivation? If a talent is really in a man, strongly, if it be given a modest beginning, he will find a way to continue its cultivation.

Sometimes a boy with whom nothing can be done in music is taken away from it, and after a little he will want of his own accord to return to its study. Such a boy will not likely waste his advantages a second time.

To persist in keeping a boy at music when it is found, after fair trial, that he has no taste for it, will not advance his general education, but will rob him of time, which, given to some other study, might influence for good his whole life.

But give him the trial.