REPORTED BY WILLIAM ARMSTRONG

There is a generally entertained idea that to know a writer is to feel a keener interest in that which he writes. To the composer this same idea is applicable.

There is a generally entertained idea that to know a writer is to feel a keener interest in that which he writes. To the composer this same idea is applicable.

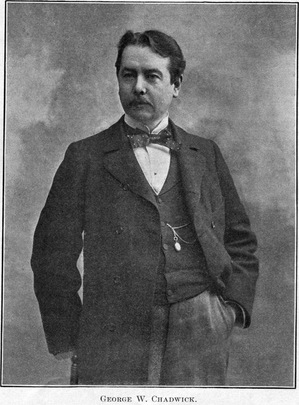

If you know Mr. George Whitfield Chadwick you will likely recall once in a while that an ancestor of his fought at Bunker Hill. If you do not happen to know him nearer than by his music, you will have been impressed by that same quality of sturdiness which is one of its characteristics.

It was a hot summer day, in London, nearly two years ago, that Sir Alexander Mackenzie said: "Chadwick has broken his leg, and is lying helpless in the hospital at Liverpool. Write to him and tell him not to give up his trip, but to come up to London as soon as he can. I have written already to say how glad we shall be to have him here."

Within two days Sir Alexander, with his big Scotch heart, had Parry, Cowen, and all the rest of the nobility of London musical life ready to give him a "home" welcome. Chadwick had brought out their compositions at Worcester, and they knew his music.

He had come abroad to study certain workings of foreign music schools in connection with his post as head of the New England Conservatory. They had no intention that he should go back without accomplishing his purpose. When he got all these urging, friendly letters he was propped up on pillows to write that he would come.

In two weeks after landing—the accident had occurred through a fall on a slippery ship-deck—he was in London. Then it was that he showed some of his inherent sturdiness. His leg was not knit; he must have suffered a deal, though he never said anything about it, and the way he got around on his crutches in this condition was something to make you hold your breath. It made me hold mine more than once, especially the getting in and out of cabs and the climbing of stairs with a stiff leg and a weak one, and the least slip ready to bring a cracking sound of the half-knit bone. But he went everywhere, he studied everything, he held a continuous reception of colleagues when he was at home. He was venturesome and self-reliant enough in getting about and bearing fatigue for a man with two sound legs, instead of no sound one to stand on.

The courage with which he bore his pain was the best part of it. He suffered enough, though he kept still about it, and when he got white and sick from pain and exertion would shut his eyes and joke.

These things naturally came into my mind the other day in Boston while Mr. Chadwick sat opposite talking about "An All Around Musical Education." Characteristic of him, the conversation was in his office on the first floor of the Conservatory, where persons were continually running in and the telephone bell played a carillon, and not in the directors' room upstairs, a state apartment with a musty smell about it, portraits on the wall, and a big, official ink well that looked quite dry standing in the middle of the table.

"The brain and mind are one thing," he said, "and technic is another. You may cultivate the fingers, the throat, or whatever else is used, but without brain and heart there is no musical education. Without a fostering of these higher attributes everything becomes merely a matter of imitation.

"First of all is the study of solfeggio, no matter what your destined branch may be; and especially necessary is this in the study of the piano. The only ones who may claim exemption from it are those who have the faculty of absolute pitch, or are correct sight singers.

"Harmony and analysis come next, and in the latter the student should have a thorough practical mastery of the composition that he is studying.

"Sight playing in ensemble, either with another piano or with stringed instruments, is a good factor in musical develpment (sic).

"Musical theory naturally plays a distinctive part in the general education.

"For the vocal pupil the chorus, and for the player of stringed instruments the orchestra, serve as valuable departments of training. For organ pupils a year, at least, of counterpoint and composition are as vital as a knowledge of the manuals.

"Before a pupil is fitted for choir training he should have had exercise of the practical kind, both in conducting church service and standard oratorio, and musical institutions of the higher sort will present these opportunities. The theoretical in all things is of inestimable worth, but before we make our real excursion into the practical we need training and supervision on the practical side of things as well.

"Two great causes of failure with students are lack of sense of rhythm and of tone, both in quality and pitch. In this latter solfeggio is of especial helpfulness. The average piano pupil thinks he listens to what he plays, but in reality he does not. Violinists and singers are forced to listen and to realize the kind of tone that they produce. The piano player puts down his finger and gets a tone, and that is just where the danger comes in. In playing a five-finger exercise he is more likely than not to go ahead mechanically, employing neither mind nor ear, yet in a five-finger exercise he can cultivate tone, both in color and quality, as readily and with greater ease than in an elaborate composition. The pianist should listen to every tone that he makes in the most elementary of exercises, for only then will he be alive to the quality of sound that he produces. Perhaps nine- tenths of the piano students fall into a mechanical way of playing, deadening to the finger sensibility; a strumming of exercises which engage neither mind nor ear. It is very much the same as if a painter listlessly dipped his brush in a single pigment from the beginning of his picture until it was finished. The drawing might be there, but it would be a meaningless monotone.

"Those who develop along such lines, if it may be called development, never get beyond the imitative stage of expression. If neither brain nor mind are exercised this is the pitfall that awaits the pianist who has his tone ready made by pushing down his finger. The singer and violinist are not in the way of such ready error in the direction of tone, and yet in modern piano playing tone-color forms as important an element as in the two first-named branches of art.

"It is important to the musician to read, write, and speak another language than his own. It broadens the mind, it strengthens the memory, it opens up new lines of thought and of information. Foreigners understand this necessity of the study of languages better than do we.

"There are so many persons who have no other education than their music. The sole mental development that they have acquired has been gained in this single study. There is a feeling, constantly growing, that the musician must be intellectually cultivated. There is a demand awaiting those who can sit with a general faculty. Many would have gotten much farther with the aid of general development, which is now of a far higher average than was the case some years back—and there is promise of a still better average in the future. Men like Parry, of university education, and broadly liberal, have done much by the force of example. The same influence is in evidence and effect in the instances of J. K. Paine, Macdowell, Parker, and others of keen, critical intellect. Musicians have found out that the public demands a broader development, and that their art as well requires it of them.

"Music is exacting in its great demands upon the time of those who study it, but strain works against development. Some time, no matter though comparatively brief, given to literature, to the study of pictures, to research on other subjects than his art will both lessen the prospect of strain, and rest and broaden the musician's mind. And the more liberal a man's education is the more his music will benefit by it. Lectures afford an excellent vehicle in this direction, both in the musical and general line, and bring without effort the full resource of others to our service.

"There is another thing in 'An All Around Musical Education' that, while not of it, is yet a factor: Exercise of some kind or other every single day."

The gist of that which followed was in this vein: Practical experience, unless directed by practical knowledge, interrupts progress only too often by experiment in the wrong direction. The most direct cut to advancement is the one made on a sound foundation of knowledge; then there is no time lost in undoing that which has been done.

There is no doubt that American methods of teaching, advanced and individual in their application to students, have done much to revolutionize study, and to place the imparting of knowledge on a broader basis. Americans are less given to falling into ruts, because they are less bound by conventionalism and by the blind faith that because a thing has been done a certain way for a certain length of time there is no other way to accomplish it.

Practicality marks the American in teaching as in every other phase of undertaking. But the practical needs exact basis to be of value, otherwise it is a fad and more or less of an experiment. The student who has been developed along practical lines and made to think for himself, finds that one thought gives rise to another; that one way of doing things suggests another along parallel lines. Some one of these will be of more value than any other in the individual development of a pupil later. He is not departing from the original course of his own proper development, but taking another way to bring that development about. It is here that the higher intellectuality comes into service, an intellectuality broadened by closer knowledge of other things than music alone, and a strengthening of the mind by branches bearing upon it.

To shut oneself up solely in text-books is to be in a greater or less degree unpractical, we then know how things should be done, but we bar ourselves out from the experience of how to do them. We take up the thoughts of others by rote, instead of making them our own in the sense of a real application, not in one, but in various ways. "An All Around Musical Education" must mean versatility, based on exact knowledge and the ability practically to apply it.