BY EDWARD BAXTER PERRY.

It was the writer’s good fortune not long since to hear, in almost immediate succession, these two leading women in the pianistic world, representatives of two widely different and rival races, and of two correspondingly diverse schools of musical expression. They are, unquestionably, the two greatest women musicians of the present generation, the one leading her sex in executive, the other in creative, work. They are, also, the only two of rank and renown who have never visited America. Hence the comparison and contrast between them is, I think, worth the reader’s attention.

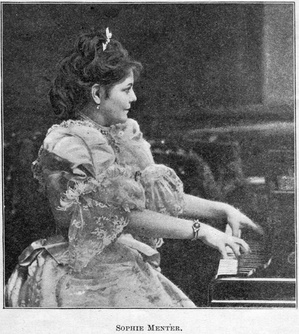

There is to day no lady pianist in Europe, and few men in the profession, who can command the same universal respect and attention as are accorded to Frau Sophie Menter, and with the best reason.

Of an eminent Bavarian family, she is by birth, as well as education, a German; although, as she has for some years filled Rubinstein’s vacant place at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and as more than twenty years ago she was made court pianist to the Emperor of Austria, she is frequently spoken of both as a Russian and an Austrian pianist. She exemplifies to the full the broad, thorough, intelligently objective German school of musical art, while possessing enough of the inherent artistic instinct and fine feminine sensibility to give warmth and color to all her work and to free it from the cold and stiff pedantry too often found in the readings of distinctively German pianists.

Of an eminent Bavarian family, she is by birth, as well as education, a German; although, as she has for some years filled Rubinstein’s vacant place at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and as more than twenty years ago she was made court pianist to the Emperor of Austria, she is frequently spoken of both as a Russian and an Austrian pianist. She exemplifies to the full the broad, thorough, intelligently objective German school of musical art, while possessing enough of the inherent artistic instinct and fine feminine sensibility to give warmth and color to all her work and to free it from the cold and stiff pedantry too often found in the readings of distinctively German pianists.

We heard her in the Liederhalle, in Stuttgart, in a regular recital program, embracing a great variety of standard works of almost every style and a few unique modern novelties. It opened with a colossal Bach-Tausig prelude and fugue, given with a breadth and majesty, a physical power and technical accuracy, which even the mighty D’Albert might have striven in vain to surpass.

Uninteresting as was this,—and, for that matter, as are all Bach fugues for piano to most listeners,—it was impossible to refuse her a tribute of profound admiration for her complete command of technical resources and the apparent ease with which she subjugated the tremendous difficulties presented. We all reverence the power to do, even when the thing done does not appeal to us, and when most wishing that the power might be applied to some more satisfactory and thankful end.

Right here, at the risk of being burned as a heretic, let me ask an honest question, to be answered candidly by each reader, in the safe privacy of his own inner consciousness, if he has not the courage to stand openly to his convictions in the frowning face of conservatism and tradition. Does any one to-day really care to listen to these Bach fugues from purely musical reasons; these monstrous tone acrostics; these gigantic thematic puzzles; these huge, mathematically exact monuments of human ingenuity and manipulative skill, which express nothing but pride in the mastery of material, and contain nothing but cold, though perfect architectural symmetry?

Let us be frank with ourselves. Do I not voice the wish of most musicians, and of practically all concert-goers, in fearlessly stating the desire that piano fugues, by Bach or whomsoever else, whether in their native barrenness or their various arrangements and disarrangements, may be henceforth dropped from the concert program as out-of-date antiquities, valuable and interesting for study in private, as an obsolete phase of the development of art, like the sphinx or pyramid, but useless as a means of expression for the intense life of our own day. Their place is the class-room, not the concert-room. I grant they are difficult to play, and that they were doubtless still more difficult to make; perhaps most difficult of all to sit and listen to; but I venture to declare, paraphrasing Macauley, that if their difficulty be not considered a merit, they have none other.

But to return to Frau Menter. The remainder of her program comprised works, most of them familiar, by Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Liszt, with a few new things by Moszkowski, and a startling, most fantastic, and ultra-modern composition of her own, entitled “Souvenir of Vienna.”

All the numbers were rendered with clear intelligence, fine emotional insight, and a facile, well nigh infallible technic, with genial warmth and evident, whole-hearted interest, but little of what might be called individual intensity, and no overwhelming passion; in a word, with the perfection of fully developed and sincerely earnest objective art, which, after all, may be the best art for all purposes and everyday use.

Her tone is full, warm, and plastic, but not remarkable for thrilling sensuous beauty. It suggests the handclasp of a large, noble, clearheaded, and kind-hearted matron, of goodly impulses but moderate enthusiasm, and just a touch of benevolent superiority.

The number by Liszt read simply “Rhapsodies” on the program, and we had a vague wonder as to whether we were to hear all fifteen in their entirety. When it was begun, however, we recognized and lost again the familiar strains, now of one, now of another, as if chasing a masquerader with half a dozen tricky disguises. All the most brilliant, telling, and popular portions of the second, sixth, and twelfth, with briefer fragments from a number of others, were dazzingly (sic) mingled and interwoven, with incredible speed and craft, until, at the close, we were left dazed, confused, breathless, and, I may add, nearly deafened, by this, undoubtedly the most brilliant and astounding concert number ever rendered upon any program.

Her own closing number, not very profound, but full of spirited rhythms, sparkling cadenzas, flashes of astounding virtuosity, bordering close upon the humorous, reveling in glissando runs in double thirds and octaves, the whole bristling with stupendous difficulties, was tossed off with careless ease, like a handful of bright-colored sugarplums thrown to a crowd of children.

In personal appearance Frau Menter was rather impressive. Her many sojourns in Russia seem to have imbued her with the real Slavonic taste in the matter of dress and decoration. Although fully fifty years of age, she was attired, except for her jewels, like a girl of sixteen. She wore a gown of light blue (most youthful of colors), with her dark hair loose and flowing over her shoulders, the ends rolled into heavy curls. I never knew a lady to appear in the concert-room wearing so many jewels. They included a complete tiara of gold and diamonds; two necklaces, one of five or six ropes of pearls and the other a kaleidoscopic display of gems of every kind and color, a foot deep; while pins, brooches, butterflies, and brilliants were thrust into every portion of her attire.

Her audience was, for Germany, wildly enthusiastic, and we left the hall with a sense of smiling exhilaration, and feeling that we had listened to the greatest artist among lady pianists.

A few weeks later, in Berlin, we were privileged to listen to the French pianist and composer, Cécile Chaminade, in a program of thirty-five selections, made up exclusively of her own compositions: a trio for violin, ‘cello, and piano; eight compositions for four hands; some fifteen songs; rendered by two French singers, contralto and tenor; the remainder solo pieces for the piano, many of which are familiar to our public.

A few weeks later, in Berlin, we were privileged to listen to the French pianist and composer, Cécile Chaminade, in a program of thirty-five selections, made up exclusively of her own compositions: a trio for violin, ‘cello, and piano; eight compositions for four hands; some fifteen songs; rendered by two French singers, contralto and tenor; the remainder solo pieces for the piano, many of which are familiar to our public.

Chaminade was at the instrument in every number, either as soloist or accompanist, playing everything without notes—in itself a feat of memory rarely witnessed, as the program lasted nearly three hours.

Considered from the standpoint of modern virtuosity, Chaminade can not be considered in the strict sense a great pianist. She lacks the strength and brilliancy, the speed, and especially the octave technic, which, rightly or wrongly, have come to be regarded as the essential attributes of these latter-day giants of the piano.

Regarded artistically, she is decidedly worthy of high consideration, though she as decidedly has her limitations, as who has not? She is neither very broad, very profound, nor very versatile; but along her special line, both as player and composer, she is unique and inimitable.

Her tone is small, fine, and pure, but witching rather than warm, suggesting a little that of Liszt in certain phases, though, of course, in miniature. At times it sparkles like a shower of hailstones with the sun shining through them. Again it is delicate, fairy-like, ineffably dainty, but never noble or passionate, with little genuine lyric quality, resembling in this respect that of all French pianists I have yet heard.

Her finger technic is fluent, crisp, and remarkably clean. The chief characteristic of her style seems to be archness, a certain graceful sprightly flavor, like the tone of conversational badinage in vogue in the best French society, so aptly designated by them as “spirituelle.” There is an evident inclination to play with her subject and her listeners, not in a would-be humorous vein, but airily, fancifully, with just a hint of coquetry. In this, her own peculiar field, she is fascinating. She has moments, too, of dreamy tenderness and pensive languor, which are wondrously attractive, but she rarely, if ever, touches the depths of profound emotion.

Chaminade’s abilities as a composer far exceed her powers as a performer, whether by natural endowment or from more complete development it is hard to say. Her piano-works are all of the same piquant, graceful type, novel and capricious in their effects, neither very deep nor very strong, but fanciful, striking, and often exquisite creations, with marked individuality, forming almost a school by themselves, and well worth playing, most of them, by artist as well as amateur.

Singularly enough, however, it is in her songs that Chaminade reaches her highest level. These are all melodious and, in the best sense of the term, effective; but should never be sung except in French. Here we find genuine emotion and plenty of it, covering a considerably varied range of moods, pleading tenderness, stirring passion, fiery energy, and even bold heroism, ably and forcibly expressed. Like most modern French songs they are preeminently singable, capable of full, adequate rendition, affording the singer a grateful and sympathetic task, and a chance to utilize the best that is in his voice and in his heart, and giving the audience an intelligible, well-balanced, and fully developed expression of some definite and concrete artistic idea. They are sensuously beautiful, if you will, but genuinely musical, with melodies that not only can be sung, but that almost sing themselves, and thrill the listener—qualities too often conspicuous by their absence in songs of the modern German school and its imitators, which, though noticeably, perhaps too laboriously, original, admirably made, and full of points and suggestions for the student, are too sketchy, too incomplete, too vague and elusive in their effects, as well as too unnatural, not. to say impossible, in their intervals and the involved complexity of their accompaniments, ever to be satisfactorily rendered or fully grasped by an audience.

Chaminade’s songs belong to the best class of French vocal compositions of the present day, and possess a certain charm and finesse in addition which is all her own, and which in large measure accounts for their popularity both in and out of France.

Her trio, too, though lacking the gravity supposed to be essential to the highest form of chamber music, in spite of the fact that neither Haydn, Schubert, nor Mendelssohn by any means always adhered to this lofty plane, was strikingly beautiful and contained many rich and strictly novel effects, full of dash and spirit, remarkable especially for its peculiar rhythms. If a work of equal merit could be exhumed as a lost manuscript, bearing the name of one of the old masters, the musical world would go mad with pride over it. But as this was only written by a woman of modern days, and a French woman at that, the German critics were inappreciative and rather vigorous in their censure.

Indeed, the entire Berlin press was harsh and, it seemed to me, decidely (sic) unjust in reviewing this concert of Chaminade’s, which would have been a credit to man or woman of any age or school. I am sorry that some of their severe comments even got into print in this country. And I question if one of their own demi-gods, if Schubert, Mozart, or even Beethoven, if called upon to furnish a program of thirty-five numbers, all from his own pen, and to perform himself all the instrumental solos, to play one part in all the concerted pieces and the accompaniments to all the songs, could have presented his contemporaries with an evening which would have compared favorably with that of Chaminade.

The criticism, when carefully analyzed, resolved itself mostly into: First, the genuine German conviction that a woman can do nothing ably, when competing in a line hitherto monopolized by men; second, the race prejudice against everything French in general, and French music and musicians in particular; and, third, a little irritation that the performer had the effrontery to remain single until well on toward middle life, and to possess little, if any, physical beauty.

Indeed, even Chaminade’s admirers could not help being rather disappointed in her personal appearance. Except for a fine figure and a fine pair of dark eyes, she can boast no physical charms, while her face is unfortunately not in her favor, when seen in profile as she sits at the piano. An extremely retreating chin, that might be called no chin at all, gives it an expression of weakness bordering upon imbecility, which very much belies her mental and artistic powers. She was dressed in a wonderful Parisian toilet, a strange combination of blue and heliotrope, which ought to have been hideous and was charming, and wore not a single gem. Its elegant simplicity was a great contrast to the much bedizened attire of Sophie Menter.

If Mlle. Chaminade had been obliged to play the program given by Frau Menter, the impression made would have been a weak one, to say the least of it; but, on the other hand, had Frau Menter been obliged to make up her program entirely from her own compositions, the evening would have been uninteresting musically and the audience very weary. Let us give honor, then, where honor is due, equally to the greatest of female composers and the greatest of female virtuosi.