From Jungle to Symphony Hall

An Extraordinary Musical Life

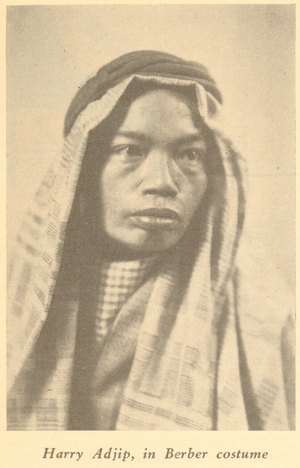

The tale of a man with four names; who was born in Hawaii, of American Indian parents; was brought up by a Malay in Singapore, as a Mohammedan; is now a Presbyterian and an active musician in Philadelphia; and whose story was secured expressly for The Etude

By RALPH G. RUTLEDGE

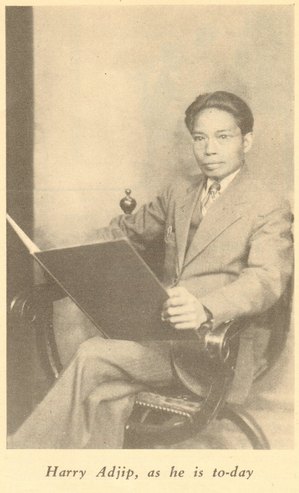

NO MORE REMARKABLE STORY has ever come into the office of THE ETUDE than this one. Harry Adjip is known to us personally, and we are convinced that his narrative is accurate to the best of his recollection. The fact that in the United States of America of 1938 he is still convinced that he has seen a Tigerman shows the power of superstition in the deep and mystic East. We have seen some of the amazingly fine copies of the scores of classics which he has made while employed by Mr. Edwin A. Fleisher in copying parts of the magnificent Fleisher Collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia, one of the greatest collections of orchestral and chamber music in America. Mr. Fleisher assures us that he is one of the most exacting and painstaking workers he has ever known. Mr. Adjip lives in Philadelphia, with his wife, who is a native of Porto Rico. None of his compositions have been published. —Editorial Note.

A Colorful Childhood

A Colorful Childhood “MY NAME is Harry Adjip, and I purpose telling first, the following facts just as they have been revealed to me by those who knew the circumstances surrounding my birth, and later the varied experiences I have had in contact with music in different parts of the world. I say that my name is Harry Adjip, because it is one of the names by which I have been known; but, as I shall later explain, I am entitled to four names, Kalow, Mohammed Ali, Hadji Mohammed Ali, and Harry Adjip. In so far as I know, I am racially an American Indian, my father having been a Cherokee born in North Dakota. His name was Maro Kalow. My mother was part Mexican Indian and Spanish. I was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, January 15,1888, where my father had a small sugar plantation.

“When I was three years old my mother died and my father was so despondent that he decided to leave Hawaii. He sold out and moved on with my sister and myself to the Orient. For a time he was in Manila, then in Hongkong, and at various places where he worked on rubber plantations. In one of these places he encountered an English circus, and this led him to Kuala Lumpur (in the state of Selangor) which, after Singapore, is the second largest city of the Malay Peninsula. It is one of the most beautiful cities of the British Empire in the Far East, with numerous fine modern buildings, excellent paving and all municipal improvements. The circus opened with my father as the director of the Wild West Show. Even then the romances of our Western plains and mountains were very thrilling to the Oriental. They liked the swift riding and the gunfire of the cowboys and the Indians, and father’s show made a very great hit.

“At that time I was about five years old. One night father went out to the jungle on a hunt with a group of men from the circus. A black leopard, which no one had seen, stealthily leaped from a tree on my father’s back, and in a few minutes, father was no more. All that he left to me was a small amount of money and an envelope with passports and papers giving my ancestry. These were handed over to a man who became my godfather. He was a Malay named Hadji Abdul Karim. He was a kind of priest, in that he was a teacher of the Koran and the Mohammedan Bible. It should be understood that the Mohammedan religion is monotheistic. That is, it believes in one god and not in the trinity as expressed in Christianity. It does, however, accept a large part of the Christian Bible and it reveres Christ like Mohammed, not as gods, but as great prophets. Even at Mecca the name of Christ,

“All of my early education was Mohammedan in the strictest sense. My godfather was a man of extraordinarily high ideals and human sympathies. I know from long residence in America that many people look upon the Malays as semicivilized in their thought. I heard from my godfather only the loftiest and noblest conception of life relations. He spoke Malay, which was my first tongue. He also spoke Arabic.

“Life in the Malay Peninsula is very different from life in the West. Once on a rubber plantation I was working with a group. burning up trees to make a clearing on the edge of the jungle. I started a fire and ran a few yards away, when I heard a call from my companions. I jumped and looked back of me, and there dangling about a foot above the place where I had been standing, was a twenty-five foot python, with a head as big as my own. If I had delayed my jump only a few seconds, this story would never have been told. My companions attacked the snake with long knives, known as parangs, and soon the reptile was no more.

Music Study Begins

“NEXT TO OUR ONE STORY BUNGALOW there lived a musician who had formerly played in a band in Manila. Music attracted me enormously and my godfather arranged to have this neighbor to give me lessons on the violin. No one ever had to encourage me to practice, for I wanted to do nothing else. The real Mohammedan has many prohibitions regarding art, music and even sport. In art, designs are permitted but drawings of animate objects are prohibited. The strict Mohammedan is not permitted to take part in football, dancing with the other sex, nor is he expected to be seen in moving picture shows. Music is supposed to be purely celestial, and therefore the real Mohammedan does not participate in it save in religious festivals, or unless he is drafted to play in a military band as a soldier. Consequently it seemed very queer for my godfather to let me take music lessons, as I believed he was my real father and that I was his own son. Later I learned the reason for his attitude. I was not his son and not racially a Mohammedan.

“NEXT TO OUR ONE STORY BUNGALOW there lived a musician who had formerly played in a band in Manila. Music attracted me enormously and my godfather arranged to have this neighbor to give me lessons on the violin. No one ever had to encourage me to practice, for I wanted to do nothing else. The real Mohammedan has many prohibitions regarding art, music and even sport. In art, designs are permitted but drawings of animate objects are prohibited. The strict Mohammedan is not permitted to take part in football, dancing with the other sex, nor is he expected to be seen in moving picture shows. Music is supposed to be purely celestial, and therefore the real Mohammedan does not participate in it save in religious festivals, or unless he is drafted to play in a military band as a soldier. Consequently it seemed very queer for my godfather to let me take music lessons, as I believed he was my real father and that I was his own son. Later I learned the reason for his attitude. I was not his son and not racially a Mohammedan.

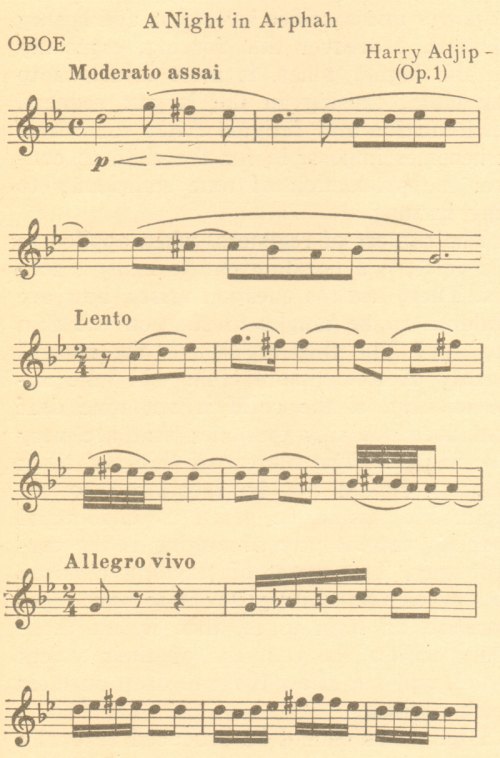

“When I was seven years of age my godfather took me on the long pilgrimage to Mecca in Arabia. We went on a ship from Singapore to Jidah. There we mounted camels and went over the sands until we came to the teeming throngs at the holy city. The camels almost invariably travel at night, because travel in the heat of the day, with the thermometer from one hundred and twenty to one hundred and thirty-five degrees Fahrenheit, is unthinkable. The Bedouins, who manage the camel trains, sing and shout all night long. When asked why they did this, they said that it was to keep the camels awake and going. If a camel goes to sleep, he calmly dumps off all of his passengers and this is dangerous. I caught the songs of the cameleers on later trips to Mecca and thereafter made them the opening theme of my orchestral composition “A Night in Arphah”

A Night in Arphah

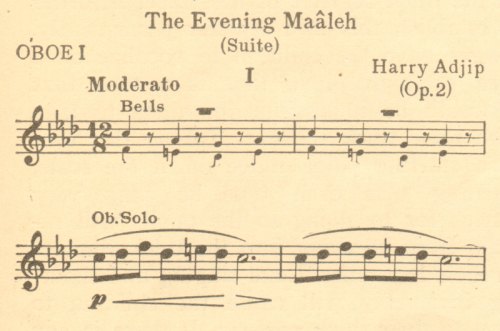

The Evening Maâleh (Suite)

“In Mecca, as a good Mohammedan child, I was permitted to kiss the sacred black stone, of the Ka’ba.* After six months stop in Mecca, we went on to Arphah. There we donned the white ceremonial robes. After a blood sacrifice of a living ox, the priest, or Eman, came in and asked what name I would like to take. In my case all that was needed was to add Hadji, so thereafter I was known as Hadji Mohammed Ali. All who have been to Mecca add the name Hadji to their names. The great life ambition of every Mohammedan is to make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once before he dies.

*The Encyclopedia Britannica says: “The black stone is a small dark mass with an aspect suggesting volcanic or meteoric origin, fixed at such a height that it can be conveniently kissed. The history of this heavenly stone, given by Gabriel to Abraham, does not conceal the fact that it was originally the most venerated of a multitude of idols and sacred stones which stood all round the sanctuary in the time of Mohammed.”

“When I was twenty-seven I returned to Mecca to kiss again the sacred stone of Ka’ha; but this time my first interest was music, as I was collecting melodies in the East wherever I could find them.

A Land of Curious Interests

“MEANWHILE, WHEN I WAS NINETEEN years old my godfather came to me one day witha bundle of papers which gave an account of my own father; and I was greatly shocked to learn that my godfather, who had been so devoted to me, was not my parent. Shortly thereafter I got a position as a valet for the manager of the rubber plantation, Mr. H. Skinner, with whom I eventually went to Sumatra. He returned to Singapore after a month, but I stayed two years, during which time I made many trips to the deep jungles. Sumatra, to me, was a land of mystery. The first thing I found out was that the natives had a poison so deadly that one drop on the end of a spear was sufficient to infect a wound and cause almost instantaneous death. It is a land of interminable superstitions. There are many varieties of animals, including tigers and the large anthropoid apes, orangutans (in Malay this merely means man of the jungle) and the rarer siamang or large gibbon, elephants, tapirs, bears, rhinoceros, wild oxen and the famous Sumatra tiger. Gibbons have long arms and legs, are not ordinarily dangerous, but they are very mischievous. They swing from tree to tree, sometimes distances of forty feet and appear to be flying. To see a group of five or six flying monkeys, all hooting at the top of their voices, is a thrilling experience.

“MEANWHILE, WHEN I WAS NINETEEN years old my godfather came to me one day witha bundle of papers which gave an account of my own father; and I was greatly shocked to learn that my godfather, who had been so devoted to me, was not my parent. Shortly thereafter I got a position as a valet for the manager of the rubber plantation, Mr. H. Skinner, with whom I eventually went to Sumatra. He returned to Singapore after a month, but I stayed two years, during which time I made many trips to the deep jungles. Sumatra, to me, was a land of mystery. The first thing I found out was that the natives had a poison so deadly that one drop on the end of a spear was sufficient to infect a wound and cause almost instantaneous death. It is a land of interminable superstitions. There are many varieties of animals, including tigers and the large anthropoid apes, orangutans (in Malay this merely means man of the jungle) and the rarer siamang or large gibbon, elephants, tapirs, bears, rhinoceros, wild oxen and the famous Sumatra tiger. Gibbons have long arms and legs, are not ordinarily dangerous, but they are very mischievous. They swing from tree to tree, sometimes distances of forty feet and appear to be flying. To see a group of five or six flying monkeys, all hooting at the top of their voices, is a thrilling experience.

“It is hard to believe, but I have seen tigers which seemed to be friendly to the people of the jungle and never to attack them. The natives believe that for hundreds of years have these tigers been friends of their ancestors; and therefore they think that they have been protected by them. One twilight a friend of mine took me to the edge of the jungle with a bowl of food. He called and a tiger came up and ate rice and chicken out of the bowl I held in my hands. I know that this story will be discredited, but it is true.

Aboriginal Music

“IN SUMATRA I felt instinctively that there was a vast treasure house of aboriginal melody and folks themes which had never been made known to the world. I therefore determined to take my violin and go into the heart of Sumatra, to see if I could not write down any melodies that I heard. Here was a land of mystery and absolutely incredible superstitions. More than this, these superstitious beliefs are so mixed up with happenings and seem so altogether miraculous that soon one finds oneself not knowing what to believe, but so amazed that one is afraid not to give credence to the wonderful reports that are heard. At that time I had gone through the seventh position on the violin and could play many of the classics. What would this mean to the people who lived in these almost impenetrable jungles? Brought up as a Malay, speaking the same language and having a short stature and the dark skin of the American Red Man, I found no difficulty in being admitted to all kinds of secret rites.

“IN SUMATRA I felt instinctively that there was a vast treasure house of aboriginal melody and folks themes which had never been made known to the world. I therefore determined to take my violin and go into the heart of Sumatra, to see if I could not write down any melodies that I heard. Here was a land of mystery and absolutely incredible superstitions. More than this, these superstitious beliefs are so mixed up with happenings and seem so altogether miraculous that soon one finds oneself not knowing what to believe, but so amazed that one is afraid not to give credence to the wonderful reports that are heard. At that time I had gone through the seventh position on the violin and could play many of the classics. What would this mean to the people who lived in these almost impenetrable jungles? Brought up as a Malay, speaking the same language and having a short stature and the dark skin of the American Red Man, I found no difficulty in being admitted to all kinds of secret rites.

“I left Padang on the coast, with the determination to make my way by boat to the interior. My first objective was Mt. Korinchi. Going up one stream, on the way in a native boat, we passed a river so choked with huge alligators and crocodiles that they had to be pushed aside. Then, the midnight depths of the jungle! At every step one must look up, then down, then to the right and then to the left, because death may be anywhere.

“Whenever we came to a settlement I played the fiddle, and the people seemed enchanted with music which had originated on the banks of the Rhine, the Danube and the Seine. I also noted down native themes. They had a primitive kind of telegraphy which was operated with gongs, as is done with hollow trees by the natives of Africa. It seems strange from an anthropological standpoint that the same basic idea of communication should be used in Sumatra and also in Africa, thousands of miles away. These odd people, by means of rhythm and pitch, can hold conversations with another tribe a score of miles away; and I have lain awake many nights listening to the gongs and drums of one tribe conversing with those of another.

“Whenever we came to a settlement I played the fiddle, and the people seemed enchanted with music which had originated on the banks of the Rhine, the Danube and the Seine. I also noted down native themes. They had a primitive kind of telegraphy which was operated with gongs, as is done with hollow trees by the natives of Africa. It seems strange from an anthropological standpoint that the same basic idea of communication should be used in Sumatra and also in Africa, thousands of miles away. These odd people, by means of rhythm and pitch, can hold conversations with another tribe a score of miles away; and I have lain awake many nights listening to the gongs and drums of one tribe conversing with those of another. “It should not be inferred that these people are savages. The Dutch settlement of Padang is a very modern city; but in the settlements in the hills are people, for instance, who still believe in Tiger-Men. They distinguish a tiger-man by the fact that he has no indentation in the flesh of his upper lip, under the nose. Such an individual is known as Remow Jaden. The natives firmly believe that he is not a man but a tiger and that this thing has hypnotized or “changed the eyes” of the individual so that he sees a two-legged animal like a man and not the yellow and black striped beast of the jungle. When the tiger-man dies, one does not find a man, but a tiger. You do not believe in ghosts. I do, because I have lived and talked with tiger-men. Only the spirit doctors (dukun) of the jungle can deal with them.

“Once, in Korenchi, the spirit priest who was also a medicine man, introduced me to a young lady. I called upon her and sang Malay songs. As we were one evening talking on the closed porch of her home, about half past eight, a handsome young man came up the steps. The moon was waning and I could not make out very clearly what he looked like, as the only light we had came from a lamp made from half a coconut filled with rosin. Every time I looked at the visitor he turned his eyes down. He could not look me in the eyes. I noted that he was watching every movement the girl made. He offered me a kind of leaf known as serih. I did not take any because I was afraid of poison. Then, after an hour or so, I suddenly looked at his lip and saw that it was straight across and had no indentation. I pulled my gun and he jumped away so quickly that I did not have time to fire. The girl immediately fainted with fright as she realized that here had been Remow Jaden, a tigerman.*

*Laugh at the Orientals’ “Tiger-man” if you will, but in remote parts of Europe in this day, a similiar (sic) superstition regarding the werewolf still persists. The werewolf is a person changed into a wolf by an evil spell but retaining human intelligence. It is reported that in the Balkans and even in parts of France, the peasants believe in werewolves.

A Purloined Treasure

“I FOUND THE MUSIC of the natives of Sumatra full of interest, and I prized my collected notes very greatly. Unfortunately they, with other valuable papers, were stolen from me later, in Calcutta. My violin was only a cheap instrument, but it was the open sesame to many places I could not otherwise have reached. It made me very popular and the Malays back in Singapore and the adjoining state of Nagary Sambilan welcomed me and provided for me. I had learned many of the Malay songs and they would listen to me sing them without end.

“I FOUND THE MUSIC of the natives of Sumatra full of interest, and I prized my collected notes very greatly. Unfortunately they, with other valuable papers, were stolen from me later, in Calcutta. My violin was only a cheap instrument, but it was the open sesame to many places I could not otherwise have reached. It made me very popular and the Malays back in Singapore and the adjoining state of Nagary Sambilan welcomed me and provided for me. I had learned many of the Malay songs and they would listen to me sing them without end.

“My next step was to Madras in India, where the blood of my father evidently showed itself, as I too, joined a circus, in which I took the part of an American Indian in the “Wild West” show. I stayed with this group for one year. The amusing thing about it was that I was the only American Indian in the “Wild West” show, and the others did not know that I was an American Indian. The circus was known as Phillips Circus, and, although entirely English, it flew the American flag, such is the reputation of the American circus in the Orient. The band was composed of Hindustani and was unbearably monotonous. Its chief piece was The Blue Danube Waltz. This was played for all trapeze acts, but when the Wild West came on we for some reason always had La Paloma.

“Then I settled in Calcutta, where I remained for a time as a teacher of the Koran, which is the Mohammedan Bible. Because I had been robbed of all my possessions, it was necessary for me, as a Mohammedan that I was at that time, to make the journey to Mecca again. There I was again officially given my name. I was then twenty-seven, was beginning to get a man’s aspect of things, and decided to devote myself to music exclusively. In various ways and with various teachers in India, England and America, I studied the laws of music and instrumentation. In Mecca I wrote my suite, “A Night in Arphah,” which has been played many times by American symphony orchestras.

“In order to make a living, I shipped repeatedly on vessels, as a part of the crew. In this way I made two voyages to England, and in 1920 I found my way to the United States, landing in New York City. At last I was in the land of my fathers, and I decided that I should become a Christian and joined the Presbyterian church. An injury to my arm put an end to my violin playing. I have devoted a large part of my time in America to copying music manuscripts, and I have thus copied thousands of works of the masters.

“The name, Harry Adjip, I assumed when I came to America. I know not why I took it. I never saw it anywhere. The sound appealed to me. I had never heard the name, and I probably am the only Adjip in the world. I have borne it for eighteen years. Although my ancestors lived in this country, centuries before the visit of Columbus, my name has no ancestral significance of any kind. Perhaps some descendant of an American Indian, somewhere, by the name of Kalow, may read this article and help me trace some of my family. Letters sent in care of THE ETUDE MUSIC MAGAZINE will reach me.”