The Music of War Torn China

By VANYA OAKES

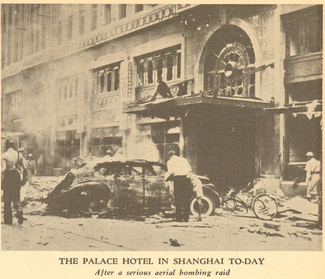

Shortly before the roar and the horrors of war broke loose from the clouds over Shanghai, the following peaceful and interesting article came to THE ETUDE. It describes the age old fight between Cathay’s music of yesterday and the music of to-day. The squabble between modernist and fundamentalist seems mere chatter compared with the thunder of the bombs bursting from the skies; yet there is an ever curious interest which clings to this primitive oriental music.—Editorial Note.

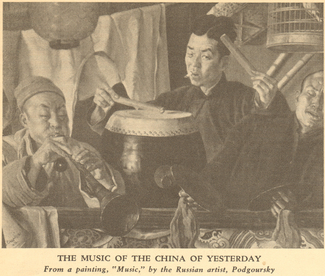

THE SIDE STREETS of Shanghai—those streets which have retained all the motley noises, the ceaselessness and the humor that belong to Chinese street life. From the second story of one of the larger shops emerge grievous sounds—the thump of a bass drum, erratic twitters from a smaller military one, and the squalls of very tinny trumpets. To style the perpetrators of this din musicians would be a gross exaggeration, for they are little more than coolies who have elected to blow and pound rather than run between the shafts of a ricksha around the city. Yet, uncouth as these sounds are, they have a certain battering rhythm, a rhythm that augments the confusion below.

Hawkers and their chattering chants so picturesque, mix in the motley crowd. Along comes a lad with the inevitable barn- boo pole across his shoulder, with baskets of miscellaneous dry goods dangling at either end. He selects a busy spot, sets up shop, and shouts out the virtues of his wares. The more subdued proclamations of a sweets vendor drift across the street; while a man with a basket of bananas does a roaring business on a nearby corner. Go a little farther, down to the river, and listen to the hi-ho—ho-hi drone of the coolies as they goose step from truck to lighter, from lighter to truck.

All these songs of toil are the most primitive of folk songs, infinitely more so than the Negro melodies. They have not grown into really mature melodies but have remained like tribal music, mere snatches of rhythm. Tribal in other ways are these chants, the “tribes” being the various trades. The origins of these trade chants have never been definitely ascertained; but certain it is that for centuries the tea carriers have passed from one generation to the next, and by word of mouth, the melody that is theirs.

Down the street comes the fiddle vendor, his wares slung across his shoulder. As he meanders along he saws at one of his instruments, pulling from it harsh and querulous sounds. This cheap and crude instrument of two strings, with its rough hair-bow, hangs in almost every dingy dwelling. And of a summer’s evening some member of the family will seat himself before the door and fiddle tirelessly and endlessly. Sympathetic fingers can coax from it a plaintive music-box melody, a pure clear tinkle—a single line of melody as undeviating, as buff-colored as the lives of the Chinese masses. This two stringed violin, the Hu Chin, is the easiest of all Chinese instruments to play; but it is rare to find those who play it well. It has a hollowed bamboo bowl shaped body, one end of which is closed with a piece of carved wood while the other is covered with snake skin. Its stemlike neck is slender and has a regular violin bridge; and the bow is likewise of thin bamboo with horse hair.

The P’i Pa is a much more complicated instrument, both in structure and in the technic it requires. P’i means the movement of the fingers away from the body, while Pa signifies their movement towards the body. The front of the instrument is made of topaz wood, the back of teak, and it has guitar-toned strings. The existent compositions for the P’i Pa are mainly descriptive of battles, of flower life, of the lament for a lover, and are full of charm. But the limitations of the instrument are apparent when heard in recital. There is too little flexibility of tone to portray any ranges of emotion; it can but suggest them.

The flute is an instrument which figures strongly in any Chinese orchestra. It is made of bamboo, and its birdlike tone is perhaps more characteristic than that of any other instrument of the delicate mentality and bodily grace which was Old China.

The Yang Ch’in, a harpsichordlike instrument, was first shaped something like a fan but later changed to resemble a butterfly. Its present contour is a compromise; across its bowl are strung, again, guitar-toned strings which are struck with very thin bamboo sticks. Like the P’i Pa, it is a very difficult instrument to master.

The Sheng is one of the oldest of Chinese musical instruments. Not dissimilar in theory to the Western organ, it produces sound by means of air motion. The lower ends of the pipes are fitted into a hollow sandalwood base. Each pipe has oblong holes on the inner side, while round holes are made on the outer surface for the passage of air. The pitch varies with the size of the reed organ.

There are an infinite variety of bells, cymbals and drums. Among them is the Yuan Ho, which is composed of ten small gongs hung on a wooden frame. Different pitches are produced on brass plates of varying thicknesses;and then there is the wooden fish—or “Buddha’s Ear”—a hollow wooden percussion instrument, played with a hammer, also of wood. These simple instruments are used everywhere in Buddhist temples, the larger ones to call the monks to prayer and the smaller ones to accompany the chants.

There are two types of orchestras, the theatrical and the classical. Both employ the Hu Ch’in and flute instruments; but in theatrical ensembles the percussion instruments dominate, while in the classical groups the flute predominates. In the Chinese theater music serves only as an escort to the action. It ushers the characters on and off the stage, and accompanies the arias and dances; but it does not, as in the operas of the West, build and sustain emotion. Classical music has survived the social and cultural upheavals of many generations, which is the more remarkable considering the wholly inadequate system of notation of Chinese music. It has retained the charm of China’s old traditions, the dignity of her sages, the grace of her reticent womanhood, the gentle bloom of the lotus blossom, the sweep of the pagoda. Yes, it has survived; but it has not advanced. It remains to-day in the embryonic stage of its development, still in the descriptive stage. It is in the same plight as its theatrical relative; it lacks form. Themes, color, rhythm—it has all of these, but it has no firmly constructed skeleton on which to drape them.

That Chinese music is made up of descriptive snatches, rather than expressions of emotions, can be readily seen in the program notes* here presented.

AUTUMN IN A HAN PALACE

* These program notes are taken from a program of the Shai Chao Chinese Music Research Institute.

This composition portrays the melancholy lot of a Court lady who was far from happy. The first movement describes her arrival at the palace and her neglect by the Emperor. Court revelries, from which she was excluded, provide the theme of the second movement. Then the final passages are indicative of the unfortunate one’s meditations upon her unhappy life.

THE DOWNFALL OF CHU

“This war song, the longest P’i P’a solo ever written, describes the conflicts of two states and the victory of Liu Pong of Han. During the second fight the Emperor Chu Han Yu is defeated and escapes. Liu Pong’s soldiers follow and overtake him. Although besieged, Hon Yu is so strong that no one dares to engage him in hand-to-hand corn- bat. Finally Liu Pong calls Chang Liang, the musician, to his side and asks him to play the folk songs of Hon Yu’s native land. When Hon Yu hears the familiar melodies, he becomes homesick and as he realizes that he will never see his native land again, he commits suicide.”

MELODY OF THE GREEN LOTUS

This composition is intended to depict the beauty of a Chinese garden lighted by lanterns and the moon.

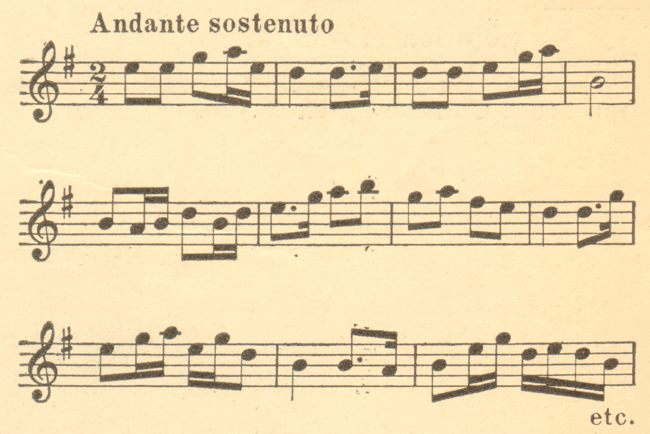

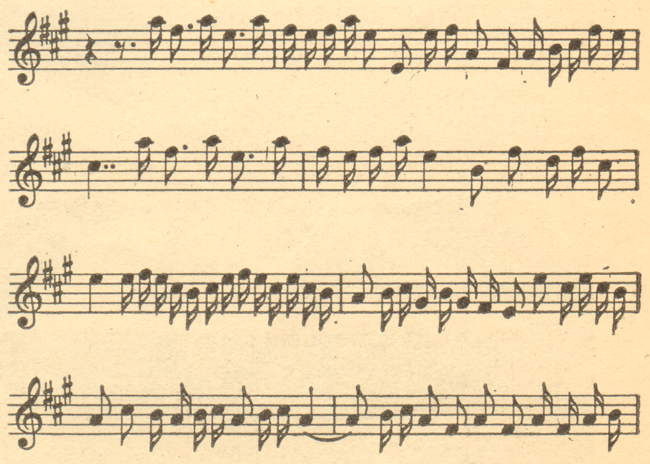

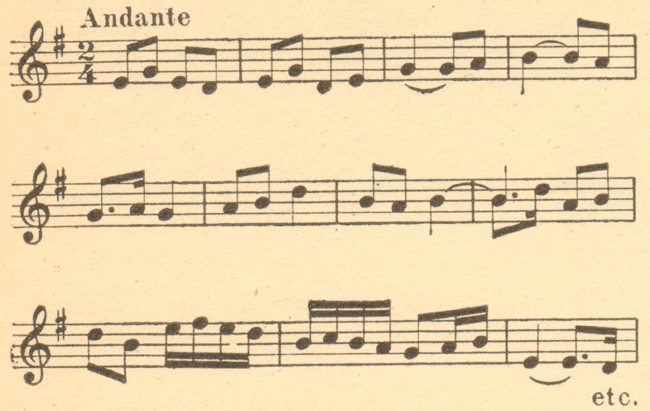

Morning Flight of Two Phoenix§

§The notation of “Morning Flight of Two Phoenix” is by courtesy of the Shai Chao Chinese Musical Research Institute. Translation from Chinese by T. Y. Soo.

“Chinese lore ranks the phoenix as the king of birds. In this fanciful composition an attempt has been made to convey this sense of majesty, resulting in an atmospheric tone poem of unusual interest and vitality.”

There have been attempts to create a form which will utilize the texture of the Western symphonic ensemble, and at the same time preserve characteristic Chinese themes as the basic motives. Aaron Avshalomoff (composer of “Kuan Yin,” “Soul of the Chin,” and “Hutungs of Peiping”) in his piano concerto (performed in Shanghai, 1935) laid before the audience the entire problem of the future of Chinese music. The adagio was performed twice, first with the Symphony Orchestra and then with a Chinese Orchestra. The majority of Chinese insist that the old instruments should be kept, that only confusion will result from tampering with them in an endeavor to produce the same richness of tone as is possessed by the instruments of the West. But the ancient instruments originated in a civilization whose art was one of suggestion; whose ideals, furthermore, were grace and delicacy, almost to the point of asceticism. Civilizations feel the imprint of universal trends, and their artistic expressions should interpret their reactions to these changes. There is a wide gap between the China of the P’i Pa and the China of to-day—whether for good or for ill it is not relevant to discuss here— and this difference in outlook must find a mode of expression. It is all very splendid for theorists to say that the fundamental characteristics of a nation do not alter with externals. A common sense survey of history would seem to bolster this opinion, but that is not the point. Granting that traditions and ideals remain unchanged, modes of living do change, and the two must be reconciled; and an art form is an interpretation of the everchanging outlook in the life of a nation. The symbols of ancient China needs must be brought to life, made vital, made representative of new surroundings. And this cannot be accomplished by clinging to meager descriptive forms and stunted instruments.

The other vulnerable point in Chinese music is its lack of harmonic development. It is purely melodic, and even the most delightful of melodies become monotonous unless principles of harmony are introduced. But, for some mysterious reason, the Chinese mind does not seem to grasp harmony readily—in theory, yes, but not in practice.

Are then the Chinese people not musical? No one with ears and eyes would support such a contention. Assuredly they are musical, but in a primitive way. They are actively musical, singing as they work. Always there is movement with their music. Life along the streets is a pageant of chants.

Debussy, in writing of the People’s Theater, said: “Let us rediscover tragedy, strengthening its primitive musical setting by means of the infinite resources of the modern orchestra and a chorus of in- numerable voices. Let us, at the same time, remember how effective is the combination of pantomimed dance accompanied by the fullest possible development of lighting.”

Can we not take this as the goal towards which experiments in Chinese music should tend ? True, the difficulties are stupendous, but not insuperable. Debussy’s suggestion involves the whole art of the theater in addition to musical composition. But there are at least two arguments in favor of it in relation to the Chinese music-drama. Much that already exists in the theater could so profitably be used—the traditional tales, some of the spectacular dances, and especially the eloquent pantomime. And secondly, even with the use of the Western symphonic ensemble, it would lose none of the Chinese characteristics.

Perhaps a national music will spring from another source; but that seems doubtful in that the already established patterns are foreign to the Chinese mind and the drama coincides with the instincts of the people who have a very highly developed sense of the theater. And composers must, after all, reflect a typical mentality of which they are a part. Thus we have from the French the impressionistic movement; from the more scientific German mind the sonata form; from Russia the color-drunk tone poems and from Italy the spectacular gore of the opera. So, too, must China uncover that particular music form which will illuminate for other nationalities her interpretation of things universal.

The obstacles seem to be of a psychological rather than a technical nature. For China, with its overdeveloped aristocracy and oversenitized culture, will not stoop to using the chants of the coolies, street cries, and so on for material on which to base its music. And another grave stumbling block is China’s resentment to outside influences. Although accepted in more practical fields, the suggestion that the West might be able to give something of value to China’s decaying art is one which is not tolerated in some influential quarters. Until, however, the Chinese composer sees his way to adapting—not adopting— some of the rich musical heritage of the West to his peculiar needs; until then Chinese music will probably remain what it is to-day, what it has been for centuries, a charming melodic description of a dwindling civilization. And, as such, it will be interesting only as are archives, not significant as music.

(Many of the active musical leaders of the China of to-day believe that the only salvation of the future of Chinese music rests in its adaptation to Western forms. During the last year a thoroughly scholarly and competent book on Chinese music has been written by Mr. Levis and published by Henry Vetch in Peiping.—Editorial.)

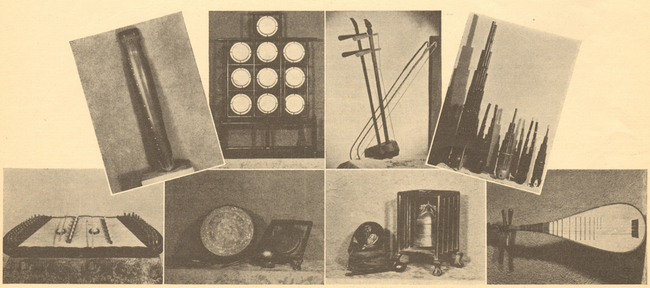

CHINESE INSTRUMENTS (click to enlarge)

Top Row, left to rght: 1. Lute; 2. Yuan Lo; 3. Er Hu; 4. Sheng. Lower Row, left to right: 1. Yang Ch’in; 2. Ku and Lo; 3. Kok Kok and Ch’ung; 4. P’i P’a.

Top Row, left to rght: 1. Lute; 2. Yuan Lo; 3. Er Hu; 4. Sheng. Lower Row, left to right: 1. Yang Ch’in; 2. Ku and Lo; 3. Kok Kok and Ch’ung; 4. P’i P’a.