WHAT YOU WANT, young man, are more audiences. You have gone about as far as you can expect to go as a student. Of course you will never cease studying and you may always learn new things from real masters of the instrument, but the time has come for you to play. You will find that the reactions you receive yourself, when you are playing alone in your room or in the studio before your teacher, may be quite different from those you experience when you are playing before audiences. The reason is very simple. When you go before an audience you become a different individual. Your nervous system is under a great strain and you do things that you never imagined you could do. All pianists know this, and many, myself included, have come to dread the experience of going before an audience. Some never recover from this experience. There is only one remedy for those who are willing to take it, and that is, more and more audiences.

“Once I heard the great Tausig say that one does not play upon the strings of the piano, but upon the heartstrings of the audience. Do not be discouraged if you fail with one audience, or with a dozen audiences. The time will come when you will adjust yourself to them. This does not mean that you should lower your art ideals. It merely means that by more and more exposure to public opinion you gradually get better control of yourself, lose your self-consciousness and say what you really have in your mind and in your heart.”

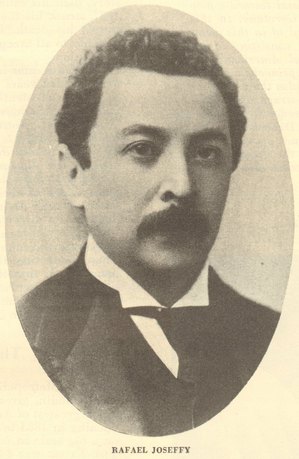

“Once I heard the great Tausig say that one does not play upon the strings of the piano, but upon the heartstrings of the audience. Do not be discouraged if you fail with one audience, or with a dozen audiences. The time will come when you will adjust yourself to them. This does not mean that you should lower your art ideals. It merely means that by more and more exposure to public opinion you gradually get better control of yourself, lose your self-consciousness and say what you really have in your mind and in your heart.”The speaker was Rafael Joseffy. These, of course, are not his exact words, but we have never forgotten the thought or the quotation from Carl Tausig. We had gone to him to secure a conference for THE ETUDE MUSIC MAGAZINE, and found him delivering this kind of baccalaureate sermon to one of his most advanced pupils. Joseffy would not consent to a conference for publication. He feared what artists call réclame and was so extremely modest and so exceedingly retiring that he confessed that when he was asked to talk he did not know just what to say.

But Joseffy died in June, 1915, and we feel justified at this time in recalling advice which may be valuable to many pupils. Apart from pedagogical works, his compositions were comparatively few. His great fame was as an artist and an educator. Born in Hunfalu, Hungary, July 3, 1852, he became a pupil successively of Miskolez. Brauer ( Heller’s pupil) , Wenzel, Moscheles, Tausig and Franz Liszt. His debut was made in Berlin, when he was twenty-three. His American debut came in 1879, at one of the symphony concerts of Dr. Leopold Damrosch. It was so sensationally successful that he determined to make the New World his home. In many ways he was one of the broadest, most sensitive, and, at the same time, most brilliant of all virtuosos. His playing of Chopin and Brahms was unforgettable; and it was Joseffy, possibly more than any other pianist, who did most to make America acquainted with the piano works of Brahms. Although opposed to sensationalism, he had a nimbleness of fingers and a velocity that have rarely been equaled, except by his famous pupil, Moriz Rosenthal.

From 1888 to 1906 Joseffy was professor of piano playing at the National Conservatory in New York City. There he imparted his artistic educational principles to a vast number of pupils and made an invaluable impression upon the musical art of America. His contribution to piano technic was ably reviewed by Edwin Hughes in the Musical Quarterly of July, 1916, one year after the master’s death.

The creative composer leaves behind in his compositions a series of monuments which, by their performance, continually revive the memory of the musician. The interpreter, on the other hand, particularly before the wide adoption of fine recordings, is liable to be forgotten by succeeding generations. Joseffy’s service to music in our country was so great that his name should be kept permanently fresh in American musical history.

Joseffy felt the responsibility of public performance the more seriously. When he carried the great works of the masters to the public, it involved a real and deep anxiety to give only the highest. Many other great artists have been overwhelmed by this responsibility, notably Henselt, whose private performances are said to have been magnificent, but who found public performance so exhausting that he played but little before large audiences.

Joseffy was a man short of stature, with very dark, penetrating eyes, curly, black hair ; and he had a very sincere, ingratiating manner. His large and important musical library (now in the Library of Congress) indicates the earnestness of his musical activities. The report of the Library of Congress (Division of Music for 1934-1935) gives five pages to a description of this splendid collection. In it are twenty-one manuscripts of Franz Liszt, including six Hungarian rhapsodies arranged for orchestra.

Joseffy wrote to Liszt in 1885, giving a picture of musical conditions in New York, as he found them fifty years ago. We are reprinting his letter:

“I take no small satisfaction in telling you that the American public exhibits far greater receptivity for serious music than reports to Europe of artistic conditions here would lead one to expect: it is indeed astonishing that Americans, animated as they are for the most part by the commercial spirit, should succeed nevertheless in preserving a wholesome, discriminating attitude toward music and that already they should have made such progress toward the appreciation of the truly noble and beautiful. I find the most telling support for this claim in the fact that my efforts to introduce works of yours that are seldom played have met always with the most enthusiastic encouragement. Only because it seems to me that news of it may interest and perhaps even surprise you, I mention, as an example of this, that your ‘Concerto in A major’—a work that you yourself do not regard as precisely ‘popular’ in its appeal, a work that requires deep understanding and a cultivated taste—that this concerto has figured in my programs, played before audiences that ran into thousands, no less than six times in the course of three seasons, a circumstance not to be under-estimated in view of the limited number of ‘classical’ programs that are offered. I find further support for this same claim of mine in the fact that these compositions represent (and indeed are) the new era. The past winter season proved in the most striking way imaginable that the public here is following energetically in the path of progress when that public broke definitely with the old Italian operatic tradition and turned with enthusiasm toward a new sun, the epoch-making opera of Germany. In this way a situation previously unheard of in this country has come about: a company consisting of respected and socially distinguished Americans has subventioned German opera in a princely way and in its own opera house, providing also the means for its further support on the most extravagant scale.”

In this writing, Joseffy makes reference to the first season of German opera which Leopold Damrosch (father of Dr. Walter Damrosch) organized and presented at the Metropolitan Opera House, in which the great Wagnerian music dramas were first heard in America, on a thoroughly adequate scale of production.