ONE OF THE FEW REMAINING PUPILS OF LISZT

When Liszt was buried, on August 3rd, 1886, thousands journeyed to Bayreuth to pay homage to his great services to musical art and to humanity. In America many of his friends and admirers went into a period of mourning.

It was the period of Rosenthal, d’Albert, Friedheim, Siloti, Weingartner, Sauer, and the American pupils, George Liebling, Carl V. Lachmund, Albert Morris Bagby, Alexander Lambert and lesser known pianists.

Having been previously instructed as to proper procedure, I kissed his extended hand and presented my introductions. And there was immediate opportunity to observe his habit of raising his bowed-glasses and hitching them on the very useful wart just above his nose. He talked a thickish German, and was kind but brief. “Kommen Sic morgen um vier Uhr (Come tomorrow at four o’clock),” said he, this being an invitation to appear at the regular class hour.

Having been previously instructed as to proper procedure, I kissed his extended hand and presented my introductions. And there was immediate opportunity to observe his habit of raising his bowed-glasses and hitching them on the very useful wart just above his nose. He talked a thickish German, and was kind but brief. “Kommen Sic morgen um vier Uhr (Come tomorrow at four o’clock),” said he, this being an invitation to appear at the regular class hour. FOR MONTHS I had been studying Liszt’s works, including the “Etudes d’execution transcendante,” several rhapsodies, the Lovedreams (there are three), and so felt well prepared to play, to say nothing of the confidence of youth and inexperience. At this lesson Della Sudda Bey (Turkish nobleman, called “Der Pasha” by Liszt), Solly Liebling, Lachmund and others performed, after which Der Meister called upon me to play. I was playing the Etude Eroica when, going full speed ahead, I felt a strong grasp on my right ear, lifting me from the seat, and heard the words “Nicht so schnell, Amerikaner (Not so fast, American) ”; for I was racing through the unison octaves. It was all in good humor, and I slowed up, and had the joy of hearing, “Gut, kommen Sie (Good, come you),” which overjoyed me indeed.

That summer we Americans formed a little colony of our own, going on picnics to the Alte Schloss (Old Castle) of the Ducal family of Sachsen-Weimar, sitting in the summer houses of Goethe and Schiller, with several trips to the Wartburg, scene of Wagner’s “Tannhäuser,” and to Bach’s birthplace, both in Eisenach, Saxony. A goodly number of the pianists of that summer became famous in after years, including Emil Sauer, now in Vienna, who played Tschaikowsky’s Polonaise from “Eugen Onegin,” with tremendous fire; Della Sudda Bey, who played St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, with extreme delicacy; Lachmund, who performed Schumann’s Toccata; and in the course of the summer the writer did the three Liebestraume; the fourth, fifth and sixth rhapsodies; the Bach-Liszt Prelude And Fugue in A minor; Henselt’s Cradle Song; and Gottschalk’s Tremolo (“Aha! der amerikanische Beethoven,” said der Meister).

A NEW LISZT MEMORIAL IN HUNGARY

A NEW LISZT MEMORIAL IN HUNGARY In commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Liszt, this memorial has been recently dedicated at Eisenstadt in Hungary.

Enter a Master Pupil

EUGEN D’ALBERT joined the class for the second summer, having come direct from Hans Richter in Vienna, who recognized his genius, both as a pianist and a composer. D’Albert, son of the Frenchman, Charles d’Albert, and a German mother, was born in Scotland, but vehemently resented being called a Scotchman, “Because a cat happens to be born in an oven,” said he, “does that make it a loaf of bread?” His introduction to the Liszt class was marked by his playing the Prelude and Fugue in E minor, from the “Well-Tempered Clavichord.” At the close Liszt asked d’Albert if he could play this Fugue in E-flat minor, which he did. Then Der Meister asked further if he could play it in octaves ? “I will try,” said seventeen- year-old d’Albert; and he did it impeccably. All of that summer d’Albert’s participation produced sensations; for he played everything with sovereign technic and spontaneity. Following a lesson he said to Lachmund and me, “Come along, I have something at home.” We climbed to his modest, single, upstairs room, where he plunged at once into something unknown to us. “Bach, of course,” said we. “No.” “Then Handel, Scarlatti or one of the Englishmen of the period.” Again no. “Anyway, one of the classics, but modernized,” we continued. “Not at all,” smiled the impish-eyed Eugen. Following the Fugue in five voices, and vast proportions, he said, “That is my ‘Suite, opus 1.’ ” To this day one frequently hears the Allemand and Gavotte.

After composing an overture for orchestra, songs, and other pieces, he tore them all up and began with this big work. When he played it for Liszt, the master scribbled on his visiting card, “To Bote and Bock, Berlin; Introducing my pupil, d’Albert, whose manuscript suite is worth attention.” This insured its publication.

One evening Lachmund told me that d’Albert was to leave Weimar the next day, whereupon I hustled to his room, saw his landlady, and rescued my own bound copy of the “Etudes d’execution transcendante” from a packed trunk. “Just like d’Albert,” said the landlady; “he takes anything he wants.”

When d’Albert announced a series of recitals at the Singakademie in Berlin, perhaps one hundred persons, including us Lisztianer, attended the first affair. Nevertheless, this recital produced such a profound impression that all the others were crowded;and one of the papers printed, “When d’Albert plays, there is something to see as well as to hear.” The small figure crouched over the keyboard; the wizened eyes; the loose, long hair falling over the face; the tremendous power and panther-like pouncing; all of these one saw when d’Albert played !

D’Albert’s various marriages, including the one to Teresa Carreño, Spanish “Lioness of the keyboard,” who was old enough to be his mother, are matters of record. His development as the composer of “Tiefland” (produced at the Metropolitan Opera House), of piano concertos, innumerable songs, and varied compositions, is musical history. His tour of the United States, with Sarasate (famous Spanish violinist and composer), was an artistic event of highest importance; a duo sonata recital in Carnegie Hall, New York, with the “Kreutzer Sonata” as principal item, was a mistake; for the two instruments produced shadow music in that auditorium.

A birthday celebration (October 22nd) was the occasion of a reunion of many Liszt pupils. At a wine supper, during the evening’s festivities, Der Meisterproposed that the company, seated around the convivial board, should sing the subject of Bach’s Fugue in A Minor, each chap to sing a tone. But the sounds issuing from our pianistic throats, were of such character that we gave up in good humored despair.

In 1886 Franz Liszt visited Paris and London, early in the spring, and many of his big works were performed. He conducted portions of his oratorio, “The Legend of Saint Elizabeth,” in London, where Walter Bache, his pupil, instituted banquets and various fetes in his honor. All this was too much for the weary soul, then seventy-five years old. Tired, from the feasting and adulation, reunions with friends of many, many years past, and ready to “go home,” he returned, this time to Bayreuth, to join his daughter, Cosima Wagner, then a widow of three years.

LISZT was noted for his wit and wisdom. Many of his aphorisms and quips have become classics, some of which are:

When Liszt’s famous pupil, Alfred Reisenauer, was engaged for a Gewandhaus Concert (comparable to the New York Philharmonic-Symphony), the entire Board of Managers met, following the public rehearsal, to consult as to permitting him to appear at the evening concert. He was to play the “Emperor Concerto” (Beethoven), and at the rehearsal he had added certain octave extensions, covering the then new keyboard of seven and one-third octaves. This was sacrilege in the eyes of the Honorable Board, so Meinherren Schleinitz, Behr and Limburger had a serious confab about it. He duly appeared.

Liszt was always willing to make any alterations in his own works, especially in sonorities or concert effects, but strongly disapproved of changes in Bach, Beethoven or Chopin. The class witnessed an unforgettable scene when a young woman performed the Ballade in A flat of Chopin, which ends with four strongly accented, square cut chords. These she played as arpeggios, with hand tossing and crossing. Dead silence followed; then Der Meister took her by the arm, escorted her to the door, and said, “Go! I want never to see you again.”

It is said that Stephen Heller, Chopin and Liszt were together on a festive occasion, when Heller perpetrated the pun, “You (Liszt) may be h—l on the piano, but I certainly am Heller.” Saint-Saëns was present when a young American pupil called to say his farewells, whereupon Liszt gallantly introduced him to Saint-Saëns as “a confrere”; much as if a mousetrap maker were to be introduced to Edison as “confrere.”

Liszt made changes in the third Lovedream, saying, “I merely wrote the notes—play them the easiest way.” Two of such changes are: (1) in the double-trill ending the first section, by grouping F-flat, A-flat and D-flat in the right hand, and E-flat, G and B-flat in the left, and playing in rapid alternation (as a trill), a tremendous effect is gained; (2) in the cadenza which goes to the top of the piano, if the left hand plays the several notes, D and E-flat, there is a great gain in facility.

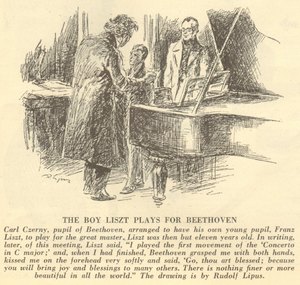

THE BOY LISZT PLAYS FOR BEETHOVEN

THE BOY LISZT PLAYS FOR BEETHOVEN Carl Czerny, pupil of Beethoven, arranged to have his own young pupil, Franz Liszt, to play for the great master. Liszt was then but eleven years old. In writing, later, of this meeting, Liszt said, “I played the first movement of the ‘Concerto in C major;’ and, when I had finished, Beethoven grasped me with both hands, kissed me on the forehead very softly and said, ‘Go, thou art blessed; because you will bring joy and blessings to many others. There is nothing finer or more

beautiful in all the world.” The drawing is by Rudolf Lipus.