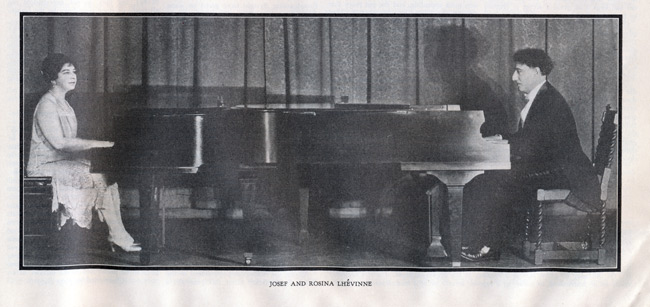

By Josef Lhévinne and Rosina Lhévinne

AS TOLD TO ROSE HEYLBUT

TWO PIANO playing is practically virgin territory and this, perhaps, is its chief interest. The possibilities of entertainment and instruction, both to the performers and their hearers, are virtually limitless. And so little work has been done! In our tours about the country, we find that there are people who regard playing upon two pianos as something of a “stunt.” Therefore, it is a privilege to explain the utter normalcy of this sort of pianistic ensemble work and to urge young pianists to try their hands at it for the sheer pleasure it affords, as well as for the sake of the rich musical literatures it opens up to them.

The first approach to four-handed playing upon two pianos is a realization of the richness of its orchestral color effects. The piano itself is symphonic in its possibilities—was it not Schumann’s dream to accentuate this unique character of the instrument he loved best?—and the combination of two pianos treated as solo instruments rather than as voice and accompaniment provides a richness of medium that can scarcely be equalled.

The first need for the further development of two piano playing is new composers, with new works which emphasize the distinctly symphonic character of the pianos. Most of the existing literature fails to do this. Rather, it treats the various themes in an easy, conversational style, permitting first one instrument and then the other to take the lead, with the result that endless repetition ensues. Rachmaninoff is the first, perhaps, to break away from this style of composition. Being pianistically-minded, he realizes that two-piano work must not give the listener the impression of a single thing split in two; that it must be formed as a rich unit of musical thought. So he arranges his thematic material in the pattern of a well- orchestrated whole, where treble and bass are not merely accompaniments for each other but means of achieving fuller shapes and deeper colors of tonal thought.

THERE IS an immense field awaiting the composer who can adjust himself to writing for pianos while thinking symphonically. An orchestral approach means more than simply an abundance of notes laid on with an over-generous hand! It requires an arrangement of materials so that each part shall contain the weight and the content of solo subjects. It requires a realization of the fact that there is no accompaniment, no “second” piano, but two solo instruments.

That, too, is the first thought to bear in mind in approaching playing on two pianos. We must not let ourselves fall into the error of regarding mere piano playing as a goal in itself. It is but one means of expressing musical thought. It is not enough simply to strike correct keys. Even before he seats himself at his instrument, the performer must devote careful study to his score, weighing phrases, balancing statements, setting off themes in contrast to each other, discovering the pattern and the plan of the unified whole which the composer wished to present.

If this is true of any sort of piano playing, it is doubly true of two-piano work, with its richer inter-weaving of thematic material. Taking an adequate playing technic quite for granted, one of the most important parts of ensemble playing is done away from the keyboards, in this delicate preparation of thematic adjustments. And once the ensemble practicing has begun, the players must keep their ears and their minds constantly alert for the shifts of balance—must know which instrument has the important message to state, the exact second at which he passes it into the hands of his partner, which piano is to be temporarily subdued and which brought to the fore. You have exactly the same problem, of course, in the interpretation of any two-handed piece, especially in the works of composers like Bach and Brahms where an elaborate contrapuntal pattern may shift from treble, to middle voice, to bass—but the solution becomes even more delicate when it must be decided at the same second by two different people.

WHICH brings us to another interesting point in two-piano work. Ensemble playing is at its best only when the players are in sympathy with each other, when they are able to think and feel in common. Certainly, any two strangers may “read music” together. They should, in fact. It is the finest practice possible for developing reading facility as well as for making the acquaintance of new music. But reading music is a very different matter from polished ensemble work. And the most sensitive performance of this kind results only when the players enjoy that friendly sympathy with each other that enables them to understand each other’s faintest nuancings of thought, even before they are expressed. This does not mean that they need necessarily agree on every point! But they must be able to follow each other in their habits of musical thought. Often, in our own concerts of two-piano music, a change of acoustics, a change of hall, even a change of mood, have demanded sudden alterations in our work which would have been impossible for people who were not accustomed to “sense” together.

Music is so elusive a means of expression that ensemble work needs some sort of spiritual “binder” to hold it sharply to the pattern of non-mechanical unity. You can argue about music forever without definitely proving anything. And interpretations vary not only in individuality but in type. Some musicians, for instance, use the printed text merely as point of departure for displaying an excess of their own individualism. Others—and theirs is the sounder musical philosophy—seek to hold their own egos in check, giving first place to the message of the composer—or, best of all, perhaps, to project themselves through a faithful adherence to the composer’s thought. This, to us, is the kernel of true artistry. Too much subjectivity, too much “personality,” and the composer is lost sight of.

MAESTRO Toscanini is the greatest example of a musician of objective approach. He is content to stay behind the man whose thoughts he interprets. If one tells Maestro Toscanini that he is a genius for bringing out this or that effect, he replies: “Genius? But it is all clearly stated in the score!” We were once present when Toscanini defined the difference between a musical amateur and a professional. “The professional follows the score exactly as it is written. The amateur does not.”

Simply to follow a score sounds easy enough; and yet it implies a life’s work of precision, of careful alertness to the smallest details of note values, of phrasing and of melodic statement. Then, only after preparation such as this, is one given the possibility of expressing the message of the music to the utmost of one’s powers.

The musical and technical preparation for two-piano playing is not in any way different from ordinary piano playing. It is simply more precise, more accurate, more orderly. Naturally this must be so, lest the fractional part of a second’s divergence in time or the faintest difference in shading blur an effect which should stand out meaningful and clear. The polishing and orderliness of piano ensemble work is even more fun than scheming out puzzles! This, however, does not imply that two-piano work need be in any way mechanical. There is strict discipline and a strict regard for routine and order; and indeed the truly artistic individuality is the one which is built up upon these. Freedom, to be freedom, needs a foundation of technical and musical orderliness.

If the emphasis has thus far been laid upon four-handed playing upon two pianos, it is because that work is of greater interest to us than four hands at one piano. Musically, its scope is richer. And, from the point of view of the playing itself, the players have greater freedom, for each one can draw upon both bass and treble, and each one is master of his own pedaling! But many students have not two pianos at their disposal and for them there is an incalculable amount of enjoyment and instruction to be derived from four-handed work upon one piano. Any hints or suggestions given for two-piano work are equally applicable here. If the library for this work is less rich in orchestral color, it is richer in the amount of excellent music available. Besides the splendid piano-duet library of original works (Schumann, Schubert, Mozart, Mendelssohn), all the great symphonies and most of the great string ensemble works (trios, quartets, quintets) have been arranged as duets to be played on one piano. And should pianists play non-piano music? Decidedly they should. There is no better way of making the acquaintance of the great symphonic and chamber music works than to play them one’s self. The piano library is rich—but the greatest music in the world is symphonic. And, without a personal knowledge of it, no one can hope to become a well-rounded musician.