The music of Brahms is so remote from popular taste that he is perhaps the least known of all the great masters. He has been surrounded by such a veil of impenetrability that he now seems to us more like some mythical deity of German legend than the genial kindly man he was at heart. It is true that his music is austere, remote, and to the musically uninitiated uninteresting ; and had he never transcribed the Hungarian Dances in the way he did it is possible that he would be wholly unknown save to musical enthusiasts. Not a few of Brahms’ admirers discount these dances and hint that they were the product of necessity rather than a genuine desire to do justice to Hungarian music. The fact is, however, Brahms was much more of a human being than are many of his admirers. His love for children is well known, and one can well believe the story told by a young American lady, traveling in Europe in 1895, that “We saw Johannes Brahms on the hotel verandah at Domodossola, and what do you think! He was down on all fours, with three children on his back, riding him for a horse.”

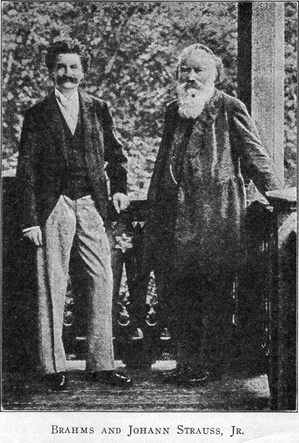

Under the circumstances, it is equally easy to believe that Brahms was very genuinely interested in music that was foreign from the kind he himself was inspired to write. His long association with the gipsy violinist Remenyi was doubtless responsible for his admiration of Hungarian music. Brahms was himself the soul of sincerity, and admired the product of the sincerity of other artists even though it differed much from the severe lines his own creations usually followed. One of the most striking instances of this is his well known admiration for Johann Strauss, the incomparable composer of the sparkling waltzes for which Vienna is famous.

Under the circumstances, it is equally easy to believe that Brahms was very genuinely interested in music that was foreign from the kind he himself was inspired to write. His long association with the gipsy violinist Remenyi was doubtless responsible for his admiration of Hungarian music. Brahms was himself the soul of sincerity, and admired the product of the sincerity of other artists even though it differed much from the severe lines his own creations usually followed. One of the most striking instances of this is his well known admiration for Johann Strauss, the incomparable composer of the sparkling waltzes for which Vienna is famous.

Widmann has recorded the great liking the master had for Der Fledermaus, the most famous of the Strauss operettas. Brahms spent a summer with Widmann, who tells us that “Brahms was very partial to the summer theatre on the Schänzli, where operas and operettas were frequently given, mostly with pianoforte accompaniment. Above all he would never miss a performance of the Fledermaus, which was given several times that summer; but he would often exclaim, “Could you but see and hear this played and sung in Vienna!”

Dr. George Henschel (now Sir George, by the way) has told us in his “Recollections of Brahms that the composer of The Academic Overture and the famous Symphony in D often declared that he would have given much to have been the composer of Strauss’s Blue Danube waltz. It is also related that the wife of Johann Strauss once asked Brahms for his autograph to put on her fan. He immediately complied with her request, writing the opening measure of the Blue Danube waltz, and putting under it, “not, alas, by Johannes Brahms.”