(Causerie Sur Les Salons Sans Musique Les Salons avec Musique et La Musique de Salon en France)

By the Brilliant Composer of Charming Salon Pieces

THEODORE LACK

Written expressly for The Etude

[Editor’s Note.—The same sparkle and interest that has made so many of Theodore Lack’s compositions popular invests the following article. The subject must have appealed to M. Lack with great interest, for he has entered into the spirit of the subject so that he virtually generates a kind of salon atmosphere to which the reader can not be insensible. M. Lack honored The Etude with an exceptionally good article in February, 1913, How the Piano is Studied in France. At that time we gave the following short biographical notes: He was born at Quimper, Finestre, France, September 3, 1846. Studied at the Paris Conservatoire with Bazin and Marmontel and has been teaching in Paris since 1863. He is an Officer of Public Instruction, Officer of the French Academy, and Examiner at the Paris Conservatoire. His best known piano composition is the very popular Idillo.]

PART I. THE SALON OF OTHER DAYS.

The salon has played a leading part in our country, particularly in the eighteenth century. It was at that period the meeting place of good company—not infrequently of bad—great nobles, famous financiers, illustrious gentlemen of the robe and of the sword, of the pen and of language well or ill put together, frequented the salon to talk about everybody and everything. New social orders, policies, scandals and slanders were formulated in the salon. Academicians were made, ministries unmade—such was the bill of fare, sugar and salt, at this charming resort. A little of everything was made there, but not much music. I cannot say a great deal about this period except from hearsay as I was not admitted into these select centres, for two reasons. First because I had not yet been born, … and that relieves me of the need of giving you the second.

Our great-grandmothers had, it is said, a peculiar faculty for maintaining a salon; the historians are all agreed on this. Historians in agreement—that astonishes you? It astonishes me, too. If it had been doctors that were in question, you would say that I was humbugging you, and you would be right for that could never be the case.

As for giving the exact date at which salons originated, that I cannot do, or at least, I can only give a very approximate date. Beginning at a remote period and coming down to modern times (that is always so easy for the author), we find the Forum and the Agora as the centre of reunion among the Greeks and Romans, where it seems they discussed very loftly matters. Perhaps that which comes nearer to the gossipy nature of our modern salon or “drawing-room” would be the Exedra of the Greeks, but if you only knew how sick I am of the Greeks and the Romans …. and you?

THE FIRST SALONS.

It is simpler to believe with Sainte-Beuve, who was a very learned gentleman, that the first salons were those of Mme. la Marquise de Lambert, Mme. du Deffand, Mme. de Tancin, and Mme. Geoffrin. The last named gave famous weekly dinners also, at which the guests were of some importance—“the fine flower of the country.” Her husband was always present, silent, unnoticed, never opening his mouth except to eat. Nobody paid any attention to him. It is said that one day, one of the guests observing his absence from the table inquired, “What has become of the old gentleman who was always at the table and never had anything to say?” And Mme. Geoffrin replied, “That was my husband. He is dead!”

That is reducing a funeral oration to its simplest form of expression, is it not? Bossuet, the famous divine took more pains over his oration at the funeral of Madame the Duchess of Orleans—it is true, however, that he was a trifle less laconic. According to many “competent” musical critics (are there any competent critics?) it was at the house of that ultra-rich melomaniac, de la Popelinière (1737), that music first made its appearance in the private salon, where it has since reigned in sovereignty. Mind you! I do not wish to say that I place the origin of music in the epoch of M. de la Popelinière. Ah, no! Music has existed since the beginning of the world; that is unquestionably true. I will explain: the word “musique” in French means the same as “chant” (song) in Greek, anything that comes from the Greek is sacred! and, as we are all possessed of a voice from birth, there is nothing to prevent us from singing at our entry into the world. And since to sing is the same thing as to make music, the origin of music must consequently date back to Adam and Eve. What objection have you to that? … nothing, parbleu! These venerable ancestors, to whom we owe the present day and all its misfortunes, including the mechanical piano, were very well able to sing duets in the garden of Paradise, their conjugal domicile.

Relating to this idea I recall the story of the lessee of a moving-picture show who shouted to the crowd assembled before the door of his establishment, “Enter, ladies and gentlemen, and you will see Adam and Eve after the photographs of the time!”

Saperlipopette! I am wandering from my subject … What do you say? Ah, yes! I was speaking of M. de la Popelinière. But since he is dead, peace to his ashes.

PART II. MUSIC SALONS OF TO-DAY.

PART II. MUSIC SALONS OF TO-DAY.

Little by little the salon of affairs gave place to the salon of music. I have spoken of the salon of yesterday; now I will speak of the salon of to-day. During my career as an active virtuoso, which extends from 1864 to 1890—since then I have devoted myself entirely to teaching and composition—I visited so large a number of salons that it would take a complete volume to number them all. I will confine myself therefore to those salons which had so much prestige at that period … and since then. This time I shall be speaking from memory of scenes in which I have been both a spectator and actor.

Salons, like individuals, have a character all their own. I am going to endeavor to show them to you in a few brief notes, written from memory without attempting to preserve any chronological order.

Music was given every Sunday at the home of the Empress Eugenie in her private apartments at the Tuileries. In order to move about the room freely one had to be as alert as a cat climbing the shelves of a dealer in porcelain. The Empress had a positive passion for old bric-à-brac! The grand piano was covered with it. To right and left of the piano a number of little stands and tables were scattered about simply covered with rare china. One had an impression that the least touch would smash it all to bits. In such surroundings, to play a Liszt Rhapsody was to invite dire catastrophe! Prudence demanded that one should play nothing beyond a Nocturne of Chopin or a Mendelssohn Song Without Words. Note bene: the Empress was a beauty, but her beauty was of a sensational kind!

Then in the Kingdom of the Pallet, there was the salon of the Princess Mathilde, cousin of Napoleon III and the good fairy of all painters,—what a delicious audience for musicians the painters make! At the salon of Monsieur Nieuwerker, superintendent of the Beaux-Arts at that time, one met “all official Paris.” I retain also a vivid recollection of the musical receptions of that exquisite, that perfect gentleman, the Count Walewski, favorite minister of Napoleon III.

At the home of President Benoit-Champi, the Great Mogul of the Magistrature, one met “le tout Palais”—all the officials of the Palais de Justice. A bevy of elegant young men was present, and young ladies with wonderful toilets—and with decidedly low-cut dresses, as might have been expected in surroundings in which the “Collet Monté” (a famous staircase) was a gracious ornament of the magisterial pretorium. Eh! Eh! I discovered there that being a grave and austere judge in no way prevented one from being a man. These gentlemen, in fact, taught me that life may be taken pleasantly and that I could “dry my eyes” as Gavroche expresses it. That great artist and charming composer for the piano, Jules Schulhoff, was an intimate friend of the house. Many a time I had the good fortune to hear him play his own works. He was a king of artists.

Pierre Véron, the wittiest of boulevardiers, founder of a celebrated journal, Le Charivari, had generally at his salon to solve the insoluble problem of making the part greater than the whole. By crowding together a little there was room in his salon for a hundred people at most, but there were always five or six hundred guests present. Those who had not an invincible determination to be asphyxiated could only enter and immediately come out; but the host’s great reputation made it necessary to be seen there.

Some excellent music was also to be heard at the salon of Adolphe Yvon, the celebrated painter of battle pictures, an artist much loved by the Emperor; also at the residence of Emile de Girardin; and at the house of my illustrious teacher, Marmontel, professor at the Conservatoire, nicknamed “the father of all contemporary pianists”; and again, at the home of Count Pillet-Will, in whose magnificent palace was heard for the first time the then unpublished Messe Solenelle of Rossini, under the direction of the composer.

THE ELEPHANT AND THE NIGHTINGALE.

If one were invited to the soirées of Doctor Mandl, one did not say, “I am going to Doctor Mandl’s,” but, “I am going to the meeting-place of the stars.” Doctor Mandl was a famous and learned laryngologist. All the most famous and all the most fashionable singers, recognizing his services to them in sickness, came in crowds to the “Friday Musicals” of the good doctor to charm the ears of his guests—hence the pretty name, “the meeting-place of the stars.” Doctor Mandl, who was something of a wit, was also a hunchback, though that is not to his discredit. The great singer Alboni, who frequently appeared on his programs, had a voice of incomparable beauty. I never heard one more lovely! Unhappily, she was physically of a size that was almost phenomenal. The master of the house compared here to an elephant with a nightingale inside! Doctor Mandl joked readily enough about his hump. At the suppers which he gave to the artists after the concerts he never failed, on sitting down at the table, to encourage his guests with the remark, “Now, my children, be gay; laugh like hunchbacks!”

Hats off, gentlemen! We are about to enter a unique salon, the like of which will never be seen again. Yes, the unforgetable Saturdays of Rossini, with their immense crowds, and such crowds! all the notabilities of every kind in the world. Here was music and what music! All the most celebrated artists in the world came here to seek the consecration of their reputation. It was a veritable little Court, but a Court reversed, in which a subject was King and in which many Kings and Queens were subject. In fact, many Sovereigns and their Consorts passing through Paris solicited the favor of assisting at one of these glorious concerts. There was nothing frigid about these receptions as one might expect with a gathering of people so becrowned. Very much to the contrary, the master of the house entertained one with so much courtesy, so much good fellowship, and with such engaging good humor, that one was completely at one’s ease. It gave one a feeling of genuine enthusiasm towards the executants.

I see him yet seated in the midst of his salon. I hear him still, with his big paternal figure, his wit so full of good natured malice, himself playing between each piece of music his little “solo” of bon mots and quick repartees with which he was so prodigal. At such times, everybody literally crowded round him in a circle so as not to lose a syllable of his brilliant conversation. He had a spontaneity of wit that was stupefying!

A friend once asked him, “Why do you never take part at the first performances of the operas of your colleagues?” To which he replied, “I do not go because if the piece is bad it bores me, and if it is good … that bores me, too.”

ROSSINI’S REPARTEE.

The story is a good one but it is not true. Rossini was benevolence and generosity itself. It must be admitted, however, that if mediocrity came into his clutches he had no hesitation about using his claws! In order to obtain his criticism a composer of this kind once brought him two melodies which he had written. “Leave them with me and I will examine them,” said Rossini. “Come again in eight days and I will tell you what I think of them.” Exactly in the time specified the composer returned to Rossini, who said to him. “Hélas! I have only had time to examine one of them … but I like the other one better.”

The splendid Sunday musicales of Mme. Erard, the wife of the great manufacturer of pianos, were much sought and much frequented by pianists. When one entered into the magnificent chateau de la Muette, with its sumptuous apartments, one felt, enveloped in an atmosphere that was, if I may be permitted to say so, maternal. Mme. Erard was full of kindness and simplicity; a lady of the greatest distinction, and of proverbial hospitality. It was at her house that I heard the celebrated virtuoso, Thalberg. His music is altogether old fashioned, I admit, but heavens, what a noble, beautiful execution he possessed! No other pianist has made the piano sing as he did; it was magical.

LISZT IN THE SALON.

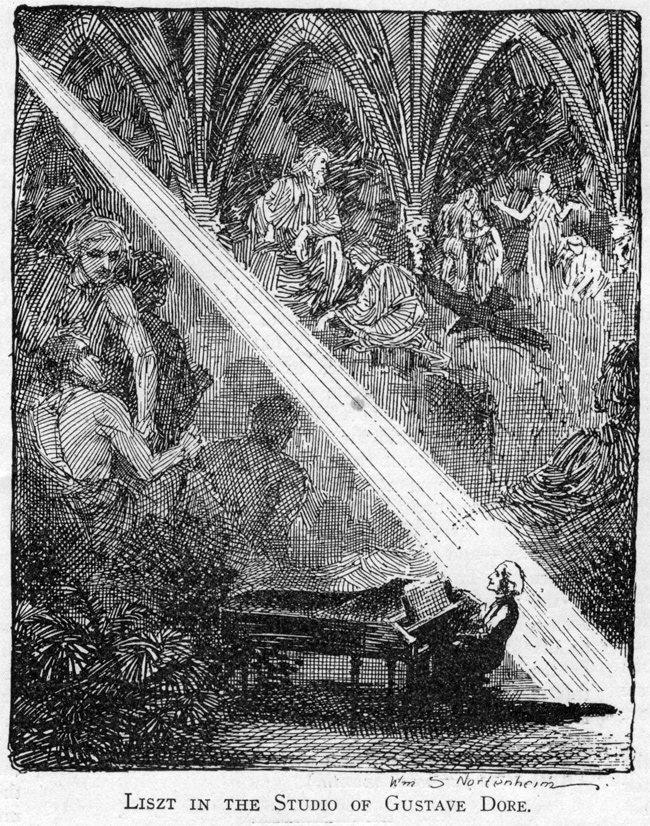

Gustave Doré, the designer, celebrated for his highly imaginative illustrations, had for a studio an ancient disused chapel. In this studio, which was of gigantic proportions, the great melomaniac held the most wonderful weekly feasts of music. At one of these, I saw and heard Liszt for the first time, about 1868 or 1869 I believe. Having taken Holy Orders in 1865, Liszt at that time was wearing the cassock that earned for him the nickname “Austerlitz” (Austere Liszt). The worldly wise might apply to him the saying, “It is not the habit that makes the monk!” On his program that evening were the two legendes: St. Francis of Assisi (Bird-Sermon), and St. Francis of Paula (Walking the Waters). Gustave Doré had painted a magnificent fresco, colossal in size, in which the figures were presented with great nobility. It was attached to the wall facing the public and above the Erard concert grand piano before which Liszt was seated,—the great Liszt with his fine Dantesque profile, his abundant silver-white hair worn very long and thrown back over his shoulders. During the performance of these two pieces, a powerful reflector threw on the scene a brilliant light that put the rest of the chapel-studio in the shade. I shall always treasure this poetic vision of art.

On the same evening I heard the celebrated pianist turn a charming compliment. Seated beside the young and pretty Mme. de B , whose beautiful shoulders were bare, the great artist contemplated their loveliness with evident delight. Suddenly perceiving this, the young lady exclaimed in pretty confusion, “Oh Monsieur Liszt!”

“Pardon me, Madame,” exclaimed Liszt, “I was expecting to see wings spring forth.”

The memory of having heard the bewitching Genie consoles me a little for being no longer young.

Much music was made—and good music I beg of you to believe me,—at the house of the celebrated dramatic author and academician Legouvé. But at his concerts no program was arranged. Whatever talent was furnished by chance was used to advantage, and chance always did wonders. One evening found us with no less than six pianists present. However, this did not interfere with us, and the pounders of the ivory would be busy still had not the mistress of the house extinguished the lights at two o’clock in the morning in order to force us to go to bed. Among the habitués of that salon were all the members of the Academy—naturally,—and all the Comédie Française—still more naturally. To complete the picture, in a retired corner of the most obscure part of the salon was often to be seen an apparition, alive for a few moments but soon to disappear, a sort of phantom in black! By a sort of tacit understanding one respected the incognito of this spectre among the living. It was the intimate friend of the master of the house, no less than Berlioz!

(M. Lack’s fascinating article will be continued in The Etude for next month.)