Department for Singers

Conducted by Eminent Vocal Teachers

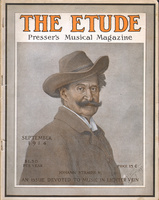

Editor for September

MR. GEORGE CHADWICK STOCK

[Mr. George Chadwick Stock comes of an old New England family, and has spent many years in the study of voice, piano and theory. He commenced his career as a boy soprano soloist in church. After his voice broke, he studied singing with many eminent teachers, and also spent ten years touring the United States. For twenty years he has been successful as a teacher in New Haven, Conn., and has well earned his popularity as a voice teacher in New England. His contributions to current musical literature have earned him many friends outside the limits of his chosen territory.—Editor of The Etude.]

SOME ASPECTS OF BREATHING.

It is important for the beginner to bear in mind the fact that every feature of vocal technic is dependent upon a well- developed respiratory action. Attack, messa di voce, portamento and legato, clear articulation of consonants without any lingering sounds after pronouncing, also intonation, blending of the registers, power, volume and intensity of tone in dramatic singing, all depend upon a complete mastery of the breath for their perfection.

Breath development in singing should always be acquired through a system of exercises which takes its cue from normal breathing or respiration—that is, natural breathing, which acts wholly independently of the will. Breathing, then, for singing is an extension to a considerable degree of the natural way of taking breath. We should begin breathing exercises with respiratory movements that are slightly deeper than we ordinarily take, and from month to month they should grow deeper and fuller. The following quotation is taken from Clara Kathleen Rogers’ Philosophy of Singing— a book which every singer should own: “What is required in breathing,” she says, “is expansion without unnecessary tension. The lungs must fill themselves in proportion as the breath is exhausted under the regulation of their own law— that of action and reaction—and not by any conscious regulating of the diaphragm on the part of the singer, as this leads inevitably to a mechanical and unspontaneous production of tone. Singers will understand me better if I say there must be no holding, no tightness anywhere, but the form of the body must remain plastic or passive to the natural acts of inhaling and exhaling, as in this way only can perfect freedom of vocal expression be obtained.”

In singing, when you have acquired correct breathing habits, you will not be conscious of the action of the diaphragm, the intercostals, or, in fact, any of the breathing muscles. If you have developed your breathing muscles properly, these muscles will work so perfectly, with such automatic precision, that you will be no more conscious of their existence in action than you are conscious of the muscles used in running or lifting, fencing or boxing. You are not to understand from this that the breathing muscles are employed in a listless manner; to the contrary, the breathing muscles in singing must always be in perfect condition (ready for instant action), without the least suggestion of rigidity. If the singing is to be of a dramatic type the action of the muscles will naturally be intensified; if of a soft and light character the work placed upon the breathing muscles will, of course, be in accord with it.

In singing, when you have acquired correct breathing habits, you will not be conscious of the action of the diaphragm, the intercostals, or, in fact, any of the breathing muscles. If you have developed your breathing muscles properly, these muscles will work so perfectly, with such automatic precision, that you will be no more conscious of their existence in action than you are conscious of the muscles used in running or lifting, fencing or boxing. You are not to understand from this that the breathing muscles are employed in a listless manner; to the contrary, the breathing muscles in singing must always be in perfect condition (ready for instant action), without the least suggestion of rigidity. If the singing is to be of a dramatic type the action of the muscles will naturally be intensified; if of a soft and light character the work placed upon the breathing muscles will, of course, be in accord with it.

The complete preservation of the integrity of tone, whether high or low, loud or soft, is dependent upon evenly sustained pressure of breath, and this pressure varies in its degree of energy according to the tone demanded. It is necessary for the student to learn at once how to manage this varying degree of breath pressure, for it is fundamental to a right play of the voice in all kinds of singing and it is of incalculable help in the equalization of the registers.

A practice which easily leads to ability to manage this particular and necessary action of the breathing is found in a simple system of whispering exercises, which eventually yields perfect and accurate management of the outgoing breath. The breathing muscles operate, in correct whispering exercises, as they should in singing.

In the use of the exercises which follow the student secures good breath management for tone production even when he is not actually using his voice. It is a means by which he can save the voice from overwork; it takes all unnecessary contraction off the throat, and places the largest share of physical effort of singing upon the strong breathing muscles, where it rightly belongs. Furthermore, it prevents a fault so common among singers—breathiness of tone—which is detrimental to all kinds of singing. This system is not new, but has been in practice by well-known vocalists, the world over, for generations. I regard the exercises that follow as of greatest value to the student of song because they invariably give the requisite stability and evenness to the breath pressure or flow; which is an indispensable condition for tone that is true to pitch, firmly resonant and well set up in all the elemental qualities. The automatic management of the breath follows as a result of the persistent employment of these exercises.

BREATHING EXERCISES.

In ordinary respiration, when the breath passes in and out noiselessly, the vocal cords are open approximately thus:

When the vowel A (as in pay) is whispered, without the slightest aspirate, the vocal cords move approximately into this position:

The breath, in passing through this very narrow opening, causes a sound which we designate as whisper.

In loud, coarse whispering the breath is wasted, whereas a fine, soft whisper, deeply placed, economizes it. For instance, a vowel sound can be spun out in a sustained whisper of this latter description for forty, fifty or even sixty seconds. This is an excellent practice to prevent waste and to gain management over the outgoing air. It also acts favorably upon the individual voice quality in singing, prom ting smoothness and good carrying power.

Begin whispering practice with the following exercise:

Take a moderate breath and count in a fine, soft, deeply placed whisper from one to ten, naming the numerals in their order of sequence. For the first few days take ten seconds to do this counting, dwelling one second on each numeral.

After three to five days extend the counting (on a single breath) from one to fifteen. Thereafter increase day after day by fives, until thirty is reached. Do this for one month, then extend the whispering to thirty-five counts, in as many seconds, on one breath.

Use your own judgment in going beyond this point, but do not overdo; your feelings will guide you aright. If the above directions seem to you to be too hurried in reaching the longer periods of counting, then take more time. Instead of dwelling a second on each numeral, simply dwell one-half second. Some pupils count to fifty in as many seconds without experiencing discomfort or exhaustion. But this is really unnecessary. In all matters pertaining to breathing exercises use common sense.

Another exercise is: Sustain “ah” in a prolonged whisper of ten seconds. Keep to this practice for a few days. After five days extend the whisper to fifteen seconds. Continue this practice for five days and thereafter sustain the “ah” for twenty seconds. Use your own judgment in going beyond this latter period. Also whisper “oh in five-, ten-, fifteen- and twenty-second periods, as above directed.

Also E, likewise.

Also A (hay), likewise.

Also OO (too), likewise.

Also Awe, likewise.

Also ah, A (hay), awe, oh, E, joined together in a prolonged whisper, dwelling three seconds on each vowel. At the end of a week extend the period of sustainment of each vowel a second or two.

In the above practice it is important to begin whispering “ah” with teeth apart about a thumb’s breadth, and do not bring them any closer together in passing from one vowel to the other. Whisper each vowel clearly and distinctly. Your lips and tongue may be relied upon to form all the vowels perfectly, unaided by any movement of the jaws. They should be passive and relaxed.

A word of explanation is necessary regarding the character of the whispering sound that is to be used in the above exercises. The correct whisper is that which is made in whispering the vowel E. Do not confuse it with the whispering sounds that are made in sounding sh, or F. These are made by the tongue and lips, respectively. In using sh, or F, breath is wasted. They sound thin and characterless, and their use is apt to induce unstable, characterless vocal timbre.

The vowel E, whispered, gives the student the cue to the right kind of whisper, and it is the whispering sound to be used on all vowels, in all the above practice. It is clean-cut, firm without stress or suggestion of being forced. It acts specifically yet with utmost gentleness upon the vocal chords, and also causes favorable activity of the entire vocal apparatus and breathing mechanism, giving them the requisite toning up preliminary to actual tone practice.

The intrinsic value of these exercises is considerably enhanced by the fact that injury to the voice by their being carelessly done is impossible because all harmful stress at the throat is eliminated. Furthermore, they are not difficult of attainment when once perfectly understood.

On (sic) of the advantage of these exercises is that any one of them can be selected and practiced anywhere or any time during the day, and, at that, without giving annoyance.

When the student has had two or three months of work on these exercises, drop the shorter periods of sustainment of the whisper and simply do those calling for fifteen seconds or longer.

Breath management is the basis of vocal technics. This feature of the art of singing can with considerable degree of certainty be gained without the immediate aid of a teacher. The earnest hope of the writer is that this sane and safe system of breathing will reach and substantially aid many students of song who for one reason or another are unable to get in personal touch with a teacher of singing.

Rely upon this: a student who has fine breath development and control is already well along on the road to success in singing. He is well prepared for the work that is to give quality, beauty and artistic results.