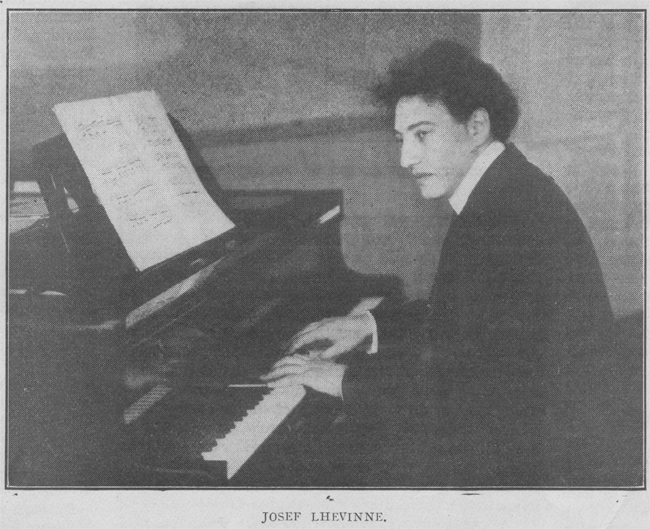

[Editor’s Note.—Although one of the last noted Russian pianists to attain celebrity in America, Lhevinne is now upon his sixth successful tour of this country. At his first appearance in New York he amazed the critics and music lovers by the virility of his style, the comprehensiveness of his technic and by his finely trained artistic judgment. Lhevinne was born at Moscow in 1874. His father was a professional musician, playing “all instruments except the piano.” It is not surprising that his four sons became professional musicians. Three are pianists and one is a flutist. When Josef was four his father discovered that he had absolute pitch, and encouraged by this sign of musical capacity placed the child under the instruction of some students from the conservatory. At six Lhevinne became the pupil of a Scandinavian teacher named Grisander. When eight he appeared at a concert and aroused much enthusiasm by his playing. At twelve he became the pupil of the famous Russian teacher, Wassili Safonoff, at the conservatory at Moscow, remaining under his instruction for six years. At the same time his teachers in theory and composition were Taneieff and Arensky. In 1891 Rubinstein selected him from all the students at the conservatory to play at a concert given under the famous master’s direction. After that Lhevinne had frequent conferences with the great pianist, and attributes much of his success to his advice. In 1895 he won the famous Rubinstein Prize in Berlin. From 1902 to 1906 he was Professor of Piano at the conservatory at Moscow. One year spent in military service in Russia proved a compulsory setback in his work, and was a serious delay in his musical progress. Lhevinne came to America in 1907 and has been here five times since then. His wife is also an exceptionally fine concert pianist.]

RUSSIA’S MANY KEYBOARD MASTERS.

“Russia is old, Russia is vast, Russia is mighty. Eight and one-half million square miles of empire not made up of colonies here and there all over the world, but one enormous territory comprising nearly one hundred and fifty million people, of almost as many races as one finds in the United States, that is Russia. Although the main occupation of the people is the most peaceful of all labor—agriculture—Russia has had to deal with over a dozen wars and insurrections during a little more than a century. In the same time the United States has had but five. War is not a thing to boast about, but the condition reflects the unrest that has existed in the vast country of the Czar, and it is not at all unlikely that this very unrest is responsible for the mental activity which has characterized the work of so many artists of Russian birth.

Although Russia is one of the most venerable of the European nations, and although she has absorbed other territory possessed by races even more venerable than herself, her advance in art, letters and music is comparatively recent. When Scarlatti, Handel and Bach were at their height, Russia, outside of court circles, was still in a state of serfdom. Tolstoi was born as late as 1828, Turgenieff in 1818 and Pushkin, the half-negro poet-humorist, was born in 1799. Contemporary with these writers was Mikhail Ivanovitch Glinka—the first of the great modern composers of Russia. Still later we come to Wassili Vereschagin, the best known of the Russian painters, who was not born until 1842. It may thus be seen that artistic development in the modern sense of the term has occurred during the lifetime of the American republic. Reaching back into the centuries, Russia is one of the most ancient of nations, but considered from the art standpoint it is one of the newest.

The folk songs that sprang from the hearts of the people in sadness and in joy indicated the unconcealable talent of the Russian people. They were longing to sing, and music became almost as much a part of their lives as food. It is no wonder then that we find among the names of the Russian pianists such celebrities as Anton Rubinstein, Nicholas Rubinstein, Essipoff, Siloti, Rachmaninoff, Gabrilowitsch, Scriabin, de Pachmann, Safonoff, Sapellnikoff and many others. It seems as though the Russian must be endowed by nature with those characteristics which enable him to penetrate the artistic maze that surrounds the wonders of music. He comes to music with a new talent, a new gift and finds first of all a great joy in his work. Much the same plight be said of the Russian violinists and the Russian singers, many of whom have met with tremendous success.

WITH THE MUSICAL CHILD IN RUSSIA.

The Russian parent usually has such a keen love for music that the child is watched from the very first for some indication that it may have musical talent. The parent knows how much music brings into the life of the child and he never looks upon the art as an accomplishment for exhibition purposes, but rather as a source of great joy. Music is fostered in the home as a part of the daily existence. Indeed, business is kept far from the Russian fireside and the atmosphere of most homes of intelligent people is that of culture rather than commerce. If the child is really musical the whole household is seized with the ambition to produce an artist. In my own case, I was taught the rudiments of music at so early an age that I have no recollection of ever having learned how to begin. It came to me just as talking does with the average child. At five I could sing some of the Schumann songs and some of those of Beethoven.

THE KIND OF MUSIC THE RUSSIAN CHILD HEARS.

THE KIND OF MUSIC THE RUSSIAN CHILD HEARS.

“The Russian child is spared all contact with really bad music. That is, he hears for the most part either the songs of the people or little selections from classical or romantic composers that are selected especially with the view of cultivating his talent. He has practically no opportunity to come in contact with any music that might be described as banal. America is a very young country and with the tension that one sees in American life on all sides there comes a tendency to accept music that may be most charitably described as “cheap.” Very often the same themes found in this music, skilfully treated, would make worthy musical compositions. “Rag-time,” and by this I refer to the peculiar rhythm and not to the bad music that Americans have come to class under this head, has a peculiar fascination for me. There is nothing objectionable about the unique rhythm, any more than there is anything iniquitous about the gypsy melodies that have made such excellent material for Brahms, Liszt and Sarasate. The fault lies in the clumsy presentation of the matter and its associations with vulgar words. The rhythm is often fascinating and exhilarating. Perhaps some day some American composer will glorify it in the Scherzo of a Symphony.

“In Russia, teachers lay great stress upon careful grading. Many teachers of note have prepared carefully graded lists of pieces, suitable to each stage of advancement. I understand that this same purpose is accomplished in America by the publication of volumes of the music itself in different grades, although I have never seen any of these collections. The Russian teacher of children takes great care that the advancement of the pupil is not too rapid. The pupil is expected to be able to perform all the pieces in one grade acceptably before going to the next grade. I have had numerous American pupils and most of them seem to have the fault of wanting to advance to a higher step long before they are really able. This is very wrong, and the pupil who insists upon such a course will surely realize some day that instead of advancing rapidly he is really throwing many annoying obstacles directly in his own path.

INSTRUCTION BOOKS.

Many juvenile instruction books are used in Russia just as in America. Some teachers, however, find that with pupils starting at an advanced age it is better to teach the rudiments without a book. This matter of method is of far greater importance than the average teacher will admit. The teacher often makes the mistake of living up in the clouds with Beethoven, Bach, Chopin and Brahms, never realizing that the pupil is very much upon the earth, and that no matter how grandly the teacher may play, the pupil must have practical assistance within his grasp. The main duty in all elementary work is to make the piano study interesting, and the teacher must choose the course likely to arouse the most interest in the particular pupil.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR VIRTUOSO-STUDENTS IN RUSSIA.

It may surprise the American student to hear that there are really more opportunities for him to secure public appearances right here in his own country than in Russia. In fact, it is really very hard to get a start in Russia unless one is able to attract the attention of the public very forcibly. In America the standard may not be so high as that demanded in the musical circles of Russia, but the student has many chances to play that would never come to him in the old world. There, the only chance for the young virtuoso is at the conservatory concerts. There are many music schools in Russia that must content themselves with private recitals, but the larger conservatories have public concerts of much importance, concerts that demand the attendance of renowned artists and compel the serious interest of the press. However, these concerts are few and far between, and only one student out of many hundreds has a chance to appear at them.

One singular custom obtains in Russia in reference to concerts. The pianist coming from some other European country is paid more than the local pianist. For instance, although I am Russian by birth, I reside in Germany and receive a higher rate when I play in Russia than does the resident artist. In fact, this rate is often double. The young virtuoso in the early stages of his career receives about one hundred roubles an appearance in Russia, while the mature artist receives from 800 to 1000. The rouble, while having an exchange value of only fifty cents in United States currency, has a purchasing value of about one dollar in Russia.

WHY RUSSIAN PIANISTS ARE FAMED FOR TECHNIC.

The Russian pianist is always famed for his technical ability. Even the mediocre artists possess that. The great artists realize that the mechanical side of piano playing is but the basis, but they would no sooner think of trying to do without that basis than they would of dispensing with the beautiful artistic temples which they build upon the substantial foundation which technic gives to them. The Russian pianists have earned fame for their technical grasp because they give adequate study to the matter. Everything is done in the most solid, substantial manner possible. They build not upon sands, but upon rock. For instance, in the conservatory examinations the student is examined first upon technic. If he fails to pass the technical examination he is not even asked to perform his pieces. Lack of proficiency in technic is taken as an indication of a lack of the right preparation and study, just as the lack of the ability to speak simple phrases correctly would be taken as a lack of preparation in the case of the actor.

Particular attention is given to the mechanical side of technic, the exercises, scales and arpeggios. American readers should understand that the full course at the leading Russian Conservatories is one of about eight or nine years. During the first five years, the pupil is supposed to be building the base upon which must rest the more advanced work of the artist. The last three or four years at the conservatory are given over to the study of master works. Only pupils who manifest great talent are permitted to remain during the last year. During the first five years the backbone of the daily work in all Russian schools is scales and arpeggios. All technic reverts to these simple materials and the student is made to understand this from his very entrance to the conservatory. As the time goes on the scales, and arpeggios become more difficult, more varied, more rapid, but they are never omitted from the daily work. The pupil who attempted complicated pieces without this preliminary technical drill would be laughed at in Russia. I have been amazed to find pupils coming from America who have been able to play a few pieces fairly well, but who wonder why they find it difficult to extend their musical sphere when the whole trouble lies in an almost total absence of regular daily technical work systematically pursued through several years.

Of course, there must be other technical material in addition to scales, but the highest technic, broadly speaking, may be traced back to scales and arpeggios. The practice of scales and arpeggios need never be mechanical or uninteresting. This depends upon the attitude of mind in which the teacher places the pupil. In fact, the teacher is largely responsible if the pupil finds scale practice dry or tiresome. It is because the pupil has not been given enough to think about in scale playing, not enough to look out for in nuance evenness, touch, rhythm, etc., etc.

MODERN RUSSIAN INFLUENCES IN MUSICAL ART.

Most musicians of to-day appreciate the fact that in many ways the most modern effects sought by the composers who seek to produce extremely new effects have frequently been anticipated in Russia. However, one signal difference exists between the Russians with ultra-modern ideas and the composers of other nations. The Russian’s advanced ideas are almost always the result of a development as were those of Wagner, Verdi, Grieg, Haydn and Beethoven. That is, constant study and investigations have led them to see things in a newer and more radical way. In the case of such composers as Debussy, Strauss, Ravel, Reger and others of the type of musical Philistine it will be observed that to all intents and purposes, they started out as innovators. Schönberg is the most recent example. How long will it take the world to comprehend his message if he really has one? Certainly, at the present time, even the admirers of the bizarre in music must pause before they confess that they understand the queer utterings of this newest claimant for the palm of musical eccentricity. With Debussy, Strauss and others it is different, for the skilled musician at once recognizes an astonishing facility to produce effects altogether new and often wonderfully fascinating. With Reger one seems to be impressed with tremendous effort and little result. Strauss, however, is really a very great master; so great that it is difficult to get the proper perspective upon his work at this time. It is safe to say that all the modern composers of the world have been influenced in one way or another by the great Russian masters of to-day and yesterday. Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui, Glazounov, Rachmaninov, Moussorgsky, Arensky, Scriabine and others, have all had a powerful bearing upon the musical thought of the times. Their virility and character have been due to the newness of the field in which they worked. The influence of the compositions of Rubinstein and Glinka can hardly be regarded as Russian since they were so saturated with European models that they might be ranked with Gluck, Mendelssohn, Liszt and Meyerbeer far better than with their fellow-countrymen who have expressed the idiom of Russia with greater veracity.