“Prince! let the mad world loud praises shout,

Every day as the bright down comes round,

I with my toast can your proudest state flout;

Here’s a health to the Kings of Sound.”

W. E. STEBBING.

For the last twenty-five years a strong feeling of attraction toward Russian compositions has been developing in this country, and what has attracted the musical connoisseur the most are the marks of boldness and originality which permeate these works where elements heretofore completely ignored are brought boldly into evidence. Not fantastic, meaningless vagaries, based on formulas most learned, but music that has sprung out of an abundance of free melodies, and having penetrated the mind of the listener, has revealed their meaning, their expressiveness, and because of it all a vigorous temperament which may be defined as leaning strongly toward the rude barbaric splendor of the orient. To quote Laroche, a well-known Russian critic: “With us nature may not be picturesque and our costumes are abominable; I will admit that everything escapes the painter’s brush or sculptor’s chisel; but our popular song offers such a profound accent, a variety so seductive and a novelty so perfect in form, that we can look to the future with full confidence and survey with satisfaction the artistic destiny of our country.”

Nigh unto a hundred years ago the classic style, disciplined in its well laid forms, modulations and rhythmic evolutions, found itself jostled by feverish expressions of endless melodies which were expressive of Romanticism, and musical taste underwent some brusque transformations. There was Rellstab the senior (1759-1813) who, on losing his property in the war of 1806, went to giving music lessons, lecturing on harmony and writing criticisms for the Vossische Zeitung. Rellstab lived in the days of Mozart (1756-1791); so did Johann Friedrich Rochlitz (1769-1842), and neither one nor the other had any use for Beethoven (1770- 1827), against whose new school of composition they hurled invectives ponderous as well as thunderous; nor did they spare the modern art of piano playing as presented by Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Yet Liszt and Chopin-speaking of piano playing-remain to this day the central figures and most potent forces of that art which has found reflection in the expositions, of some extremely clever and original Russian composers, who, eschewing the mathematical evolutions of a certain class of music-producers, have cut loose from idealism and preëstablished rules, and given way to natural sentiments which in their country breathe strong revolutionary ideas.

Some years ago Miss Anna Alice Chapin wrote in a Boston review that “Every line of Milton, properly read and properly assimilated, helps us in the study of Bach;” preface all serious study of music with Bach and you will prepare yourself for a thorough, most delectable appreciation of those Russians, each of whom, if once heard, may boldly exclaim in the language of Marshal McMahon, “J’y suis, et j’y reste!” It is not music as yet much known in this country; at least nothing much outside of a few centers where two or three of the great minds have penetrated orchestrally and where some minor piano works have found favor at the hands of temperamental pianists. The few fearless ones have pulled the curtain aside and revealed to us manifestations of an art built out of inviting melodies and punctuated with peculiar rhythms that breathe the very spirit of Russian people and of their manners. To know this school it is wise also to know each one of the composers in order to appreciate his individual value and peculiar tendencies.

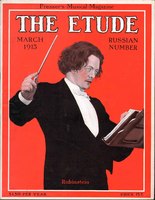

The two most important representatives, looked upon as such because of their peculiar position as international composers, are Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky. Dr. Walter Niemann defines them as “occidentalists,” because they show influences of the German Romantic School, namely Schumann. Anton Rubinstein (1830-1894), excepting his famous fourth piano concerto in D minor, recently revised by Leschetitzky, is seldom heard unless we read of some ambitious school damsel who exhibits her skill in Kamennoi-Ostrow, presumably the twenty-second number of that Album of twenty-four portraits. But who is the musician-the real article-who does not know and love his Barcarolle, Op. 50, No. 3, or for that matter the one listed as Op. 30, No. 1. Rubinstein’s piano music enjoys a popularity which will last long after some of his contemporaries are forgotten, and offers food, mental and digital, for all sorts of players. Le Bal, four brilliant dances for the piano, are particularly bright and attractive: the Polka has a “go,” the Polka Mazurka is characteristic and elegant; the Valse is light and dainty, while the Galop sparkles with exuberance. Just the kind of music to indulge in during the seasons of festivity and joy. Then there are two numbers, Souvenir and Nocturne, in the famous Album de Peterhof which give us glimpses of fecundity in abundance as well as a sane and vigorous temperament. For the opening of a Russian program his Prelude in E, Op. 24, would serve to good purpose. Rubinstein, who used to get much amusement out of his critics, expressed himself thus in a letter to a friend: ”The Jews consider me a Christian, and the Christians a Jew; the classics look upon me as a Wagnerite, and these again as a classicist; the Russians take me for a German, and the Germans for a Russian;” all this because he was independent and did not pretend to belong to any special clique.

THE INFLUENCE OF TCHAIKOVSKY.

Of Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), preëminently an orchestral composer of programatic intent, much has been written; there is a vigor and tunefulness that have so completely gilded the difficulties of his more involved harmonies that critics have remained open-mouthed and astonished, and for the greater part, wholly charmed. Many of his piano pieces are expressive and quite Russian, and if not particularly claviermaessig the manner in which he uses his melodies stamps him forthwith as a man who made music his art and not his trade. I will first mention the famous Chant sans Paroles, Op. 2, and a Barcarolle known as June. His opus 72, being among the very last of his works, shows the individuality of the author in respect of his melody, rhythm and harmony. Thus No. 3, Tendre Reproches of expressive mood (Grade IV), No. 7, Polacca di Concerto with a great deal of octave work (Grade VI), No. 11, Valse Bluette, a simple melodic study (Grade IV), No. 16, Valse à cinq temps, a remarkably fine study (Grade V-VI), and No. 18, Scene dansante (Grade VI), but above all the soulful Romance, Op. 51, No. 5, dedicated to Mme. Vera Rimsky-Korsakoff, all of which pieces require a facile, responsive touch, but above all a fair amount of digital independence and a wide range of intelligence as to tone effects and interpretation.

Cesar Cui (born in Wilno in 1835), son of a French officer and a Lithuanian lady, to-day a Lieutenant-General in the Russian army, belongs to the “five” who went at it with firm determination to establish in Russia a national and rational development of the art which, some fifty years ago, was practically engulfed in German or Italian phraseologies. Cui, in particular, fought the battle with a sharp pen, and victory was with the young Russians. It is wise to know the two great principles that are consistently borne out in their works of importance: the theory of “continual flow” and “obliteration of tonality” as heretofore practiced. The one gives us long lines of unbroken melody, the other is a simplification of matters, and should have been adopted long ago, particularly by those whose musical thoughts travel in more than one groove. Notwithstanding the fact that Cui’s. music is Russian, at times even eastern, much of it shows a western influence, particularly that of the French School. Of course, the two Suites, one dedicated to Liszt, the other of four pieces, to Leschetizky, would interest rhythmically as well as with their color and sonority a well advanced player; so would the first of Three Impromptus, Op. 35, and the extremely enticing Valse, Op. 31, No. 3, in which movement-not speed-is a sine qua non. Of much lesser difficulty are his expressive Miniatures, twelve charming morceaux that should figure on every conservatory program of lower grades. Then again for players technically qualified and of intellectual appreciation we have a rich choice of multi-colored preludes (25 Preludes, Op. 64); Numbers 17 in A flat, 21 in B flat and 25 in C, though more brilliant if played in C sharp, would serve many purposes if properly studied.

Another member of the group of “five” was Mily Balakirev (1837-1910), a programatic symphonist par excellence, who nevertheless found time to write the now famous Fantasy Islamey built on original oriental motifs, and intended by the composer to be played by pianists thoroughly equipped technically and intellectually; aside from this work we have a wonderfully expressive Complainte, the Second Scherzo in B flat minor, a Toccata of great strength and a Valse di bravura dedicated to D’Albert, all of these calling for brilliant powers of perception and a well-developed technique.

THE RUSSIAN MENDELSSOHN.

Of the younger followers in the steps of Cui, Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakoff (1844-1908), Moussorgsky (1830-1881), and Borodin (1834-1887), we find Anton Arensky (1861-1906), who was unquestionably the leader, both in spirit and in his tremendous activity, though German commentators have tried to anchor him in German waters by dubbing him the Russian Mendelssohn. To my perception an influence of Tchaikovsky is often perceptible in his melodic development, nevertheless all his compositions excel in originality, color and most graceful invention. Absolutely free from German influence are his Intermezzo from Op. 5. Three Bigarrures, Op. 20, Esquisses, Op. 52, Nos. 4 and 5, and the charming suite of six numbers known as Arabesques, Op. 67, peculiar in their highly expressive Cantilena. Nothing better for a sustained singing style could be found among Russian composers than these offerings of Arensky.

An important member of this group is Anatole Liadov (1855-), whose compositions show a remarkably good influence since it is that of Bach and Chopin; polyphony and cantilena! Technically they represent an intelligent pianism based on Chopin’s style of writing, while a freshness and reckless development of motifs lend themselves easily to the production of splendid curves and sweeping contours that in themselves constitute a form. In his Biroulki a set of fourteen bagatelles edited by Karl Klindworth, he tells little stories in melodies and rhythms of a fascinating kind and within easy grasp of the so-called Grade IV. The tide of Russia’s musical awakening has been of a startling character in the compositions, rich in poetical lore, of this talented pupil of Rimsky-Korsakoff. Liadov is today perhaps the most perfect contrapuntist of Russia. As near as I can find out counterpoint is not a favorite science; everybody hates it! Beethoven got tired of Papa Haydn’s lessons; Schubert always thought of mastering it, while Schumann had but a limited knowledge of it. Wagner went at it also with a view of mastering the art in extento, but gave it up in six months, having mastered enough to fulfill all requirements for the musical elucidation of his own poetry. Liadov has delved into counterpoint with persistency, and his offerings so developed present something more than wooden successions of chords or collections of technical ‘“Melodies” stiffer than wood. Study his three Ballet Movements, Op. 52, extremely expressive in their respective 3/4, 2/4 and 5/4 rhythms, or the two Preludes, Op. 13, No. 1, and Op. 27, No. 1, not very difficult, and the difficult Barcarolle, Op. 44, and you will forget the intents of florid or any other counterpoint in the charm of these brilliant offerings, while the Etude, Op. 5, will always prove to be an acceptable number technically (about Grade V) and musically for a well conceived program. Of great charm, to those who have reached the fifth grade, would be his Petite Valse, Prelude Op. 10, Two Pieces, Op. 24, No. 2 being a Berceuse developed in the style of Chopin; an original sketch Sur la prairie, a companion piece to Borodin’s On the Steppes of Asia; a charming Idylle Op. 25, an original Mazurka rustique, Op. 31, dedicated to the writer of these lines, and its companion opus number, a soulful Prelude, besides very clever variations of a Polish theme, Op. 51.

(A second section of Mr. de Zielinski’s article will appear in The Etude for April.)