An interview secured expressly for The Etude with the distinguished Virtuoso Pianist

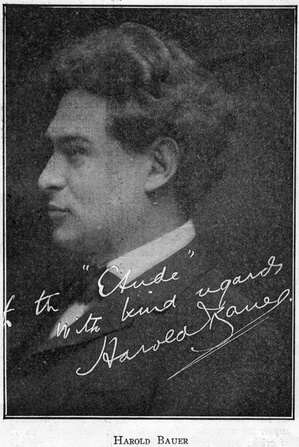

HAROLD BAUER

[Editor’s Note.—Mr. Harold Bauer, who is now making his sixth tour of America, is one of the most interesting personalities of the musical world. In the ordinary understanding of the word, his training has been singularly paradoxical, since it has differed radically from the paths in which most of the celebrated pianists have gone. Mr. Bauer was born in London, England, April 28, 1873. His father was an accomplished amateur violinist and through him the fortunate son had home associations which enabled him to become very intimately acquainted with the most beautiful chamber music literature. As a boy Mr. Bauer studied privately with the celebrated violin teacher Pollitzer. At the age of ten he became so proficient that he made his début as a violinist in London. Thereafter he made many tours of England as a violinist, meeting everywhere with flattering success. In the artistic circles of London he had the good fortune to meet a musician named Graham Moore who gave him some ideas of the details of the technic of pianoforte playing, which Mr. Bauer had studied, or rather “picked up” by himself, without any thought of ever abandoning his career as a violinist. Mr. Moore was expected to rehearse some orchestral accompaniments on a second piano with Paderewski, who was then preparing some concertos for public performance. Mr. Moore was taken ill and sent his talented musical friend, Mr. Bauer, in his place. Paderewski immediately took an interest in Mr. Bauer, and, having learned of his ambition to shine as a violin virtuoso, advised him to go to Paris to study violin with Gorski. After that Bauer met Paderewski frequently and received advice and hints, but no regular instruction in the ordinary sense of the term. In Paris Bauer had no chance whatever to play, and the first year and a half was a period of privation which he is not likely to forget. Then a chance came to play in Russia as accompanist for a singer making a tour in that country. The tour was a long one, and in some of the smaller towns Bauer played an occasional piano solo. Returning to Paris with his meagre savings he found that his position was little, if any, better than it had been before his trip. Still no opportunities to play the violin were forthcoming. Then the pianist who was to take part in a certain concert was taken ill (the pianist was Stojowski) and Bauer was asked to substitute. His success was not great, but it was at least a start. As other requests for his service as a pianist followed, he gradually gave more and more attention to the instrument and through great concentration and the most careful mental analysis of the playing of other virtuosos, as well as a deep consideration of the musical æsthetical probems (sic) underlying the best in the art of pianoforte interpretation, he has risen to a unique position in the tone world. Mr. Bauer is a wholesome, vigorous, sincere thinker who likes to delve deep into the truths of musical art, and we feel that this interview is one of the most individual and instructive The Etude has ever had the honor of presenting. ]

THE IMMEDIATE RELATION OF TECHNIC TO MUSIC.

THE IMMEDIATE RELATION OF TECHNIC TO MUSIC.

“While it gives me great pleasure to talk to the great number of students reached by The Etude, I can assure you that it is with no little diffidence that I venture to approach these very subjects about which they are probably most anxious to learn. In the first place, words tell very little, an, in the second place, my whole career has been so different from the orthodox methods that I have been constantly compelled to contrive means of my own to meet the myriads of artistic contingencies as they have arisen in my work. It is largely for this reason that I felt compelled recently to refuse a very flattering offer to write a book on piano playing. My whole life experience makes me incapable of perceiving what the normal methods of pianistic study should be. As a result of this I am obliged with my own pupils to invent continually new means and new plans for work with each student.

“Without the conventional technical basis to work upon, this has necessarily resulted in several aspects of pianoforte study which are naturally somewhat different from the commonly accepted ideas of the technicians. In the first place, the only technical study of any kind I have ever done has been that technique which has had an immediate relation to the musical message of the piece I have been studying. In other words, I have never studied technique independently of music. I do not condemn the ordinary technical methods for those who desire to use them and see good in them. I fear, however, that I am unable to discuss them adequately, as they are outside of my personal experience.

THE AIM OF TECHNIQUE.

“When, as a result of circumstances entirely beyond my control, I abandoned the study of the violin in order to become a pianist, I was forced to realize, in view of my very imperfect technical equipment, that in order to take advantage of the opportunities that offered for public performance it would be necessary for me to find some means of making my playing acceptable without spending months and probably years in acquiring mechanical proficiency. The only way of overcoming the difficulty seemed to be to devote myself entirely to the musical essentials of the composition I was interpreting in the hope that the purely technical deficiencies which I had neither time nor knowledge to enable me to correct would pass comparatively unnoticed, provided I was able to give sufficient interest and compel sufficient attention to the emotional values of the work. This kind of study, forced upon me in the first instance through reasons of expediency, became a habit, and gradually grew into a conviction that it was a mistake to practice technique at all unless such practice should conduce to some definite, specific and immediate musical result.

“I do not wish to be misundertood (sic) in making this statement, containing, as it does, an expression of opinion that was formed in early years of study, but which nevertheless, I have never since felt any reason to change. It is not my intention to imply that technical study is unnecessary, or that purely muscular training is to be neglected. I mean simply to say that in every detail of technical work the germ of musical expression must be discovered and cultivated, and that in muscular training for force and independence the simplest possible forms of physical exercises are all that is necessary. The singer and the violinist are always studying music, even when they practice a succession of single notes. Not so with the pianist, however, for an isolated note on the piano, whether played by the most accomplished artist or the man in the street, means nothing, absolutely nothing.

SEEKING INDIVIDUAL EXPRESSION.

“At the time of which I speak, my greatest difficulty was naturally to give a constant and definite direction to my work and in my efforts to obtain a suitable muscular training which should enable me to produce expressive sounds, while I neglected no opportunity of closely observing the work of pianoforte teachers and students around me. I found that most of the technical work which was being done with infinite pains and a vast expenditure of time was not only non-productive of expressive sounds, but actually harmful and misleading as regards the development of the musical sense. I could see no object in practicing evenness in scales, considering that a perfectly even scale is essentially devoid of emotional (musical) significance. I could see no reason for limiting tone production to a certain kind of sound that was called “a good tone,” since the expression of feeling necessarily demands in many cases the use of relatively harsh sounds. Moreover, I could see no reason for trying to overcome what are generally called natural defects, such as the comparative weakness of the fourth finger for example, as it seemed to me rather a good thing than otherwise that each finger should naturally and normally possess a characteristic motion of its own. It is differences that count in art, not similarities. Every individual expression is a form of art; why not, then, make an artist of each finger by cultivating its special aptitudes instead of adapting a system of training deliberately calculated to destroy these individual characteristics in bringing all the fingers to a common level of lifeless machines?

“These and similar reflections, I discovered, were carrying me continually farther away from the ideals of most of the pianists, students and teachers with whom I was in contact, and it was not long before I definitely abandoned all hope of obtaining, by any of the means I found in use, the results for which I was striving. Consequently, from that time to the present my work has necessarily been more or less independent and empirical in its nature, and, while I trust I am neither prejudiced nor intolerant in my attitude towards pianoforte education in its general aspect, I cannot help feeling that a great deal of natural taste is stifled and a great deal of mediocrity created by the persistent and unintelligent study of such things as an ‘even scale’ or a ‘good tone.’

“Lastly, it is quite incomprehensible to me why any one method of technic should be superior to any other, considering that as far as I was able to judge, no teacher or pupil ever claimed more for any technical system than that it gave more technical ability than some other technical system. I have never been able to convince myself, as a matter of fact, that one system does give more ability than another; but even if there were one infinitely superior to all the rest, it would still fail to satisfy me unless its whole aim and object were to facilitate musical expression.

“Naturally, studying in this way required my powers of concentration to be trained to the very highest point. This matter of concentration is far more important than most teachers imagine, and the perusal of some standard work on psycology will reveal things which should help the student greatly. Many pupils make the mistake of thinking that only a certain kind of music demands concentration, whereas it is quite as necessary to concentrate the mind upon the playing of a simple scale as for the study of a Beethoven sonata.

THE RESISTANCE OF THE MEDIUM.

“In every form of art the medium that is employed offers a certain resistance to perfect freedom of expression, and the nature of this resistance must be fully understood before it can be overcome. The poet, the painter, the sculptor and the musician each has his own problem to solve, and the pianist in particular is frequently brought to the verge of despair through the fact that the instrument, in requiring the expenditure of physical and nervous energy, absorbs, so to speak, a large proportion of the intensity which the music demands.

“With many students the piano is only a barrier—a wall between them and music. Their thoughts never seem to penetrate farther than the keys. They plod along for years apparently striving to make piano-playing machines of themselves, and in the end result in becoming something rather inferior.

“Conditions are doubtless better now than in former years. Teachers give studies with some musical value, and the months, even years, of keyboard grind without the least suggestion of anything musical or gratifying to the natural sense of the beautiful are very probably a thing of the past. But here again I fear the teachers in many cases make a perverted use of studies and pieces for technical purposes. If we practice a piece of real music with no other idea than that of developing some technical point it often ceases to become a piece of music and results in being a kind of technical machinery. Once a piece is mechanical it is difficult to make it otherwise. All the cogs, wheels, bolts and screws which an over-zealous ambition to become perfect technically has built up are made so evident that only the most patient and enduring kind of an audience can tolerate them.

THE PERVERSION OF STUDIES.

“People talk about ‘using the music of Bach’ to accomplish some technical purpose in a perfectly heartbreaking manner. They never seem to think of interpreting Bach, but, rather, make of him a kind of technical elevator by means of which they hope to reach some marvelous musical heights. We even hear of the studies of Chopin being perverted in a similarly vicious manner, but Bach, the master of masters, is the greatest sufferer.

“It has become a truism to say that technic is only a means to an end, but I very much doubt if this assertion should be accepted without question, suggesting as it does the advisability of studying something that is not music and which is believed at some future time to be capable of being marvelously transformed into an artistic expression. Properly understood, technic is art, and must be studied as such. There should be no technic in music which is not music in itself.

THE UNIT OF MUSICAL EXPRESSION.

“The piano is, of all instruments, the least expressive naturally, and it is of the greatest importance that the student should realize the nature of its resistance. The action of a piano is purely a piece of machinery where the individual note has no meaning. When the key is once struck and the note sounded there is a completed action and the note cannot then be modified nor changed in the least. The only thing over which the pianist has any control is the length of the tone, and this again may not last any longer than the natural vibrations of the strings, although it may be shortened by relinquishing the keys. It makes no difference whether the individual note is struck by a child or by Paderewski—it has in itself no expressive value. In the case of the violin, the voice and all other instruments except the organ, the individual note may be modified after it is emitted or struck, and in this modification is contained the possibility of a whole world of emotional expression.

(A second part to Mr. Harold Bauer’s interview, entitled “The Road to Expression,” will be published in The Etude for April.)