AN UNKNOWN TRUTH ABOUT VOICE PRODUCTION.

[In presenting the following article to the readers of The Etude, we must ask them to recollect that the sole mission of the editor is to seek for the truth in all its phases. It is not within the editor’s province to determine arbitrarily what is right and what is wrong. Consequently many articles are presented in this magazine which may be exactly opposite to the principles maintained by some of our teachers. We cannot take one side and maintain that that side only is right. We must present all sides of a question. The broad and earnest reader wants to read all sides and then form his own opinions. The following articles are from a series by a conscientious, highly educated and gifted English teacher. Although they are radical in some respects, they will surely stimulate sensible people to do some profitable thinking and “auto-inspection.” As a matter of fact, hundreds of teachers of voice do not now concern themselves to any great extent in teaching different registers. Judging from the correspondence received at this office, there has seemed to be a popular tendency in this direction for some time. We do not attempt to say which is right. We simply aim to be fair to all earnest thinking investigators. Again let us mention the fact that The Etude does not permit controversies or polemical discussions. If the following opinions do not coincide with your own, remember that with the able staff of editors engaged to write for the Voice Department of The Etude there must necessarily be some representative of your own views.—Editor of The Etude.]

For the last twenty years I have been persistently seeking to draw the serious attention of the musical profession and the musical public generally to certain remarkable facts which have come to my knowledge in connection with the subject of voice production. Experience must have shown many teachers that the percentage of vocal success is entirely out of proportion with the amount of effort put into vocal study. In seeking a remedy for such a position let us glance briefly at some of the best known vocal systems, particularly those which are supposed to be based upon a scientific foundation.

One of the most widely known systems of voice training is that of which the late Manuel Garcia may be regarded as the leading exponent. According to this authority, whose name is held in deservedly high esteem by musicians and scientists alike, the human voice consists of three registers; that is to say, it is separated by “breaks” into three portions which are produced in three essentially different ways.

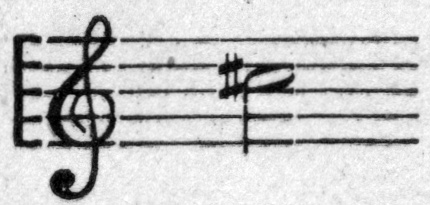

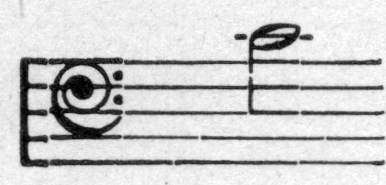

The lowest of these portions is termed the chest register; the middle portion is termed the medium or falsetto register; and the highest is termed the head register. The chest register extends from the lowest note of which the human voice is capable as far as

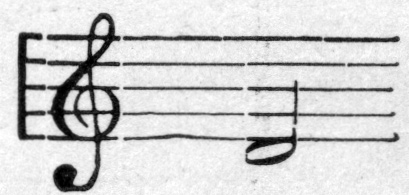

It can be carried a considerable distance beyond that limit, but that note is regarded as marking the highest point to which it is safe to take it, and this no matter what the character or compass of the voice may be. The medium register (also called by Garcia the falsetto register) is considered to begin at the point at which the chest voice ends (though it is admitted that it can be carried a little lower), and its upper limit is said to be

To take it beyond this point is considered, as in the case of the chest register, to be dangerous. The head register, according to this theory, commences at

and extends from this poin (sic) to the highest note which the human voice can produce.

Another popular system follows the lead of Emil Behnke, whose laryngoscopic investigations, carried out in conjunction with Dr. Lennox Browne, led him to formulate a theory similar to, and to a great extent founded upon, that previously propounded by Madame Seiler, of America.

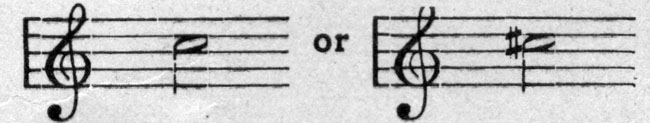

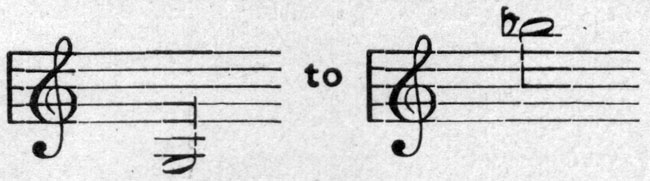

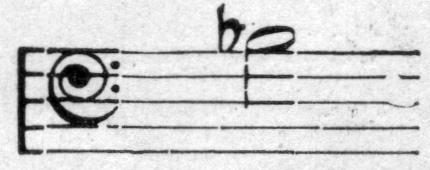

According to this theory the human voice has four more or less perceptible “breaks” in it, and as each of these “breaks” is believed to be caused by an essentially different laryngeal mechanism, it follows that the voice as a whole possesses five registers. It is admitted, however, that some of the “breaks” are difficult to discover and are of minor importance, and the advocates of this theory are, for the most part, disposed to agree with Garcia that, broadly speaking, the voice may be said to consist of three registers, while they believe, as Garcia appears formerly to have done, that two of them may be subdivided. Behnke calls these three registers the thick, the thin and the small registers. The lowest or chest register he subdivides into lower and upper thick, and the middle register into lower and upper thin. As to the position of the “break” between the thick and the thin registers—that which, setting aside subdivisions, we may call the first main “break”—he is in substantial agreement with Garcia; but as regards the position of the second main “break”—that between the thin and the small registers—the two authorities are widely at variance. Behnke places this at

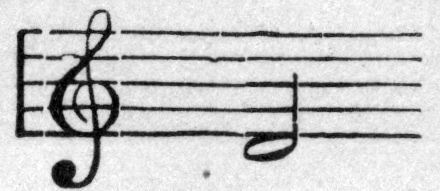

while Garcia places it at

which is just where Behnke makes one of his minor “breaks.” Since both these systems claim to rest upon a scientific basis and to be supported by laryngoscopic evidence, this discrepancy, coupled with the difference of opinion as to the number of the registers, is worthy of particular notice. It proves, at any rate, that even the laryngoscope, great as is its value, is not quite so infallible a guide as some would have us believe.

Besides the two systems of voice-production the distinctive features of which have just been described, there is a third which demands our attention.

FOUND IN THE “OLD ITALIAN SCHOOL.”

Many present-day singing teachers recognize a system of voice-production based on the assumption that the human voice has two registers, and two registers only. “The old Italian Masters,” says Sir Morell Makenzie (sic) in his book, The Hygiene of the Vocal Organs, “recognized only two registers of the human voice, the ‘chest’ and the falsetto or ‘head,’ the two latter terms being synonymous.”

It should be mentioned that he refers to a treatise by a famous Italian singing master of the seventeenth century in support of his statement. I am disposed to think that the Italian term voce di testa, or head voice, was in use at a much earlier date than the term falsetto. When the latter term began to be employed, those who adopted it applied it to a voice of the same kind as that which was formerly called head voice, but not wittingly. When the upper register of the male voice was very thin and weak they called it falsetto, believing that it was sometimes unnatural and that it ought not to be used. When, on the other hand, it was found to be fairly strong and substantial they took it to be an essentially different kind of voice and advocated its use under the name of head voice.

The term head voice has also, where men’s voices are concerned, been employed by some teachers in a very different sense. As used by these teachers it means a kind of voice which is produced by the same laryngeal mechanism as the ordinary chest register, but is so softened and restrained by the extreme elevation of the soft palate that its character is very greatly altered. This is sometimes called mixed voice, the idea being, that in those cases in which it is used, the two registers, like twins in the once famous ballad, have in some mysterious way “got completely mixed.” Those who take this view with regard to the male voice hold that the so-called falsetto is not a natural but an artificial or acquired voice—something which ought not to exist, and must on no account be encouraged to do so. Thousands of men, however, could be found to testify that the voice to which, in their case, the term falsetto is now applied is identical with the voice which they used in boyhood.

The two-register theory, though often supposed in the present day to be unscientific and in direct conflict with the evidence of the laryngoscope, has the support, amongst other authorities, of the late Sir Morell Makenzie (sic), and also of the great German physiologist, Johannes Müller. The former, who made a laryngoscopic examination of the throats of between three and four hundred good singers, writes as follows in the book to which I have already referred:

The actual mechanical principles involved are only two. In singing up the scale the vocalist feels that at a certain point he has to alter his method of production in order to reach the higher notes. This point marks the break between the so-called “chest” and “head” registers, or what may be called the lower and upper storys of the voice. This division of the voice is fundamental, all others being based either on convenience for teaching purposes or on fantastic notions derived from subjective sensation or erroneous laryngoscopic observations.

The real secret of voice production does not lie in breathing, despite the oft-quoted Italian proverb to the effect that he who knows how to breathe knows how to sing. It is not in the lungs, but in the larynx that the solution of the vocal problem is to be found, as the following facts attest:

1. That there are in men, as well as in women and children, voices in which separate registers do not exist—voices which are produced in one way only throughout the whole of their compass.

2. That where two distinct registers are found, if the upper register be carried downwards as far as it will go, and energetically exercised, the result is that both registers are benefited.

3. That in voices which possess two registers vigorous and persistent exercise of the lower or chest register is injurious both to itself and to the upper or head register.

4. That the voice which is commonly called falsetto is, under certain conditions, capable of development to such a degree as entirely to transform its character.

VOICES WITHOUT SEPARATE REGISTERS.

Among men as well as among women and children, voices are to be found which do not possess separate registers, but are produced throughout their whole compass in one way only. Sir Morell Mackenzie, in his Hygiene of the Vocal Organs, refers to the fact incidentally more than once, but does not draw any conclusions from it. A few modern theorists endeavor to explain it much as follows: The voices in question, they say, undoubtedly appear to be produced by the same laryngeal mechanism throughout, but this is not really the case. A change of production does and must take place somewhere, but the different registers are so well and perfectly blended by nature that no alteration of the mechanism is discernible.

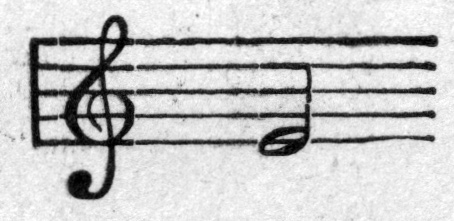

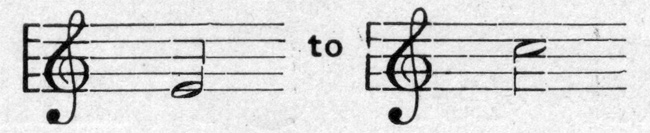

In reply to this let me first of all refer to my own voice, which in boyhood was a good example of the kind now under consideration. It was a pure soprano voice of good quality, extending from

In its production Mother Nature was my only guide. So far as I was concerned registers had no existence. My voice in those early years was produced from one end of its compass to the other without any change whatever in the nature of the laryngeal mechanism. One mode of production only was employed, namely, that which is said to belong rightly to the “middle” or, as some call it, the “thin” register—the latter term being altogether a misnomer as far as my voice was concerned, seeing that there was nothing thin about it. On the contrary, it was always quite firm and strong, no matter whether the upper, the middle, or the lower portion was being made use of, while no amount of exercise ever seemed to tire it. Sometimes I sang treble; sometimes alto, but whichever part I sang I always produced my voice in the same way. Sir Morell Mackenzie says that he is able to affirm, from the examination of a great number of cases, “that boys who sing alto always use the chest register.” It only shows how, on this subject, even the most acute and conscientious observer is liable to be led astray. I have a complete and vivid recollection of what my voice was like and the way in which it was used both before and immediately after the great change, commonly spoken of as the breaking of the voice—and I can assure my readers that the chest register, taking the term in its ordinary meaning, did not exist in my voice until after the “breaking” period had commenced.

Having shown that the boy’s voice may be, and sometimes is, produced in its entirety by one laryngeal mechanism alone, it is not necessary to occupy time and space in proving that the same thing is true concerning the female voice, because as regards the means of production, there is no difference between the two cases. I come then to the question of the adult male voice. Is it possible, the reader may ask, to find among men’s voices any which are capable of being produced from the bottom to the extreme upper limit of the compass without a radical change in the vocal mechanism? The prevalent opinion among musicians certainly seems to be that it is not. The natural voice of a man, they argue, is the chest voice, and the upper limit of this chest voice, as they know from their own experience, is not identical with the upper limit of their vocal compass. Beyond the range of the chest voice is another voice, produced by a different mechanism—the voice in which they can imitate or, more accurately speaking, caricature the tones of a woman’s voice, commonly known as falsetto, in fact, as the terms chest voice and falsetto had come to have any meaning for me I began to notice that there were adult male voices in which these separate registers had no place, and I may add that I noticed also, as a distinguishing feature of these voices, the exceptional ease with which they were produced. Since the time I am referring to I have met with a good many other voices of the same kind, and in nearly every case the voice was one which had never been trained. I am also quite satisfied in my own mind that these voices are not only apparently, but actually produced by one laryngeal mechanism only. Strange to say, I can also claim in support of it the testimony of the laryngoscope. This little instrument is generally supposed to be the unswevering (sic) ally of the multi-register theorists. In the hands of an independent investigator like Sir Morell Mackenzie, with no pet theory to substantiate, it reveals something quite undreamt of in their philosophy.

In the book, to which I have more than once referred, Mackenzie records several instances of professional singers, male as well as female, whose voices, when examined by means of the laryngoscope, were found to have only one mode of production throughout the whole of their compass, “sound flowing on,” to quote his own words, “in one unbroken stream from the lowest note to the highest.” He also cites the physiologist, Dr. Wesley Mills, of Montreal, as having noticed the same phenomenon. Both these authorities regard the voices in question as being extremely rare and exceptional. Possibly, however, it is not so exceptional as might be supposed.

EXERCISING THE UPPER REGISTER.

The second fact which demands our attention is that, in voices in which two separate registers are discernible, if the upper register be carried downwards as far as it will go and energetically exercised, the result is that both registers are benefited; that is to say, the upper register is strengthened while the lower is improved in quality and rendered easier to produce.

I regard the “two register” division of the voice as the correct one in all cases where any division at all is necessary. I fully agree with Sir Morell Mackenzie that the break which occurs in passing from the chest register to the voice immediately above it is the only break which is caused by a change in the mechanical action of the larynx. Other breaks, where they are not wholly imaginary, are for the most part very slight, and are caused by sudden modifications of tone brought about by the action of certain parts of the resonance apparatus, namely, the soft palate, pharynx and tongue.

As to the beneficial influence which the exercise of this head register has over the lower or chest register—and this is the point I wish to emphasize—the fact is one which, notwithstanding its importance to singers in general and to men singers in particular, seems to have entirely escaped attention. Yet it is a fact which can easily be verified. Let any man who uses the chest register exclusively try the effect of resting this voice for a few months and exercising in place of it, at not too high a pitch, the other voice—the voice which he probably calls falsetto. Then let him go back to the chest voice and see whether it is not all the better for this novel treatment. It is quite possible he may have been told that to treat the voice in this way is the worst thing he can do for it. In voices which possess two registers, vigorous and persistent exercise of the chest register is injurious both to itself and to the head register.

After what has already been said it is perhaps scarcely necessary to explain that by head register I mean all that voice which is no part of the chest register. That is to say, I use the term not in the limited sense in which Garcia and many others use it, but in the sense in which, as we have seen, there is good reason to believe it was used by the old Italian singing masters. In the great majority of cases the exclusive use of the chest register is looked upon as a matter of course, and the regular and systematic exercise of this voice two or three times a day is enjoined upon the pupil as an indispensable condition of progress. What is the usual result? A deterioration which is in direct proportion to the amount of exercise to which the voice has been subjected.

In many cases the injury that is done does not attract any particular attention. The ordinary listener is so much impressed by the general improvement in the style of the singer, and by the artistic manner in which he has learnt to manage his voice, that he loses sight of the fact that the voice itself is not as good as it was originally. In the same way the singer also is misled. Indeed, not only may he be unconscious that his voice has been in any way impaired, but he may even be under the impression that it has decidedly improved. He does not realize that this increase of tone is simply and solely owing to an increase of effort.

It is well known that where the woman’s voice is concerned the head register is injuriously affected by the forcing up of the chest register beyond a certain point. But as regards the man’s voice, owing to the views which everywhere prevail as to its nature and treatment, the fact that the exercise of the chest register may have a weakening effect upon the head register is one with which neither pupil nor teacher is at all likely to concern himself.

A NEW PHASE OF VOCAL DEVELOPMENT.

The last fact needs fuller explanation. The voice commonly called falsetto, which is believed to be of no use whatever, can be strengthened and extended to the very bottom of the vocal compass, and by means of suitable exercises perseveringly continued, can be so completely transformed as to lose entirely the peculiar falsetto quality and to become what may best be described as a new kind of chest voice. This will equal the ordinary chest voice in fulness and power, but vastly excels it in every other respect.

I have already described my voice as it was in boyhood. After the “breaking” or changing period arrived, instead of possessing one voice, as formerly, I found myself with two. The one, produced in a way which was new to me, extended from an octave lower to middle C; the other produced as in childhood, from

The lower voice could be carried two or three tones higher, but only by a manifest effort of a kind which I had never experienced when a boy. The upper voice could be carried a tone or two lower, but was then so weak as to be of little or no use. The former of these two voices I called chest voice, and the latter falsetto. The voice which I called falsetto was simply the remains of the old soprano voice of my earlier years.

I was told that at this “breaking” period the singing voice ought to be rested entirely. So, for a time, I gave up singing. As well as I can recollect, I allowed about eighteen months or two years to elapse before I re-commenced. I did not find, however, that the rest had done the voice any perceptible good. The only way in which I could use the voice to any advantage was in singing alto. I sang in this way in a choir for some years, and also joined a male voice quartet party, in which, as the quality of the upper register was good, it proved of some value. For the lower notes up to

I employed the chest voice, and for the notes above that point the voice which I had now begun to call falsetto.

When I was about two and thirty years of age I went to consult a teacher of singing, whose method of training had been somewhat strongly recommended to me by one or two of my musical friends. Up to that time, although I had had a good deal of musical education in other directions, I had never taken any singing lessons, because I did not consider my voice worth training. He told me that he made great use of head voice, and gave me some exercises for carrying the head voice down. I assumed that his meaning of the head voice and falsetto were practically the same thing, though I afterwards found that this was not his opinion.

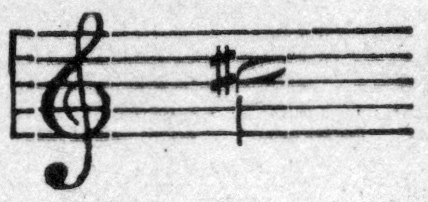

The method of training was as follows. The chest register was to be used only for those notes which were quite easy to produce. The break between the chest and head registers had its position determined by this consideration, and was not regarded as fixed by nature at any given point. The head register was to be employed from the highest point at which it could be produced without undue strain to the lowest point at which any appreciable tone could be obtained. At first the chest voice was carried up to

while the head voice was not taken below

except in a certain arpeggio exercise, which almost of necessity brought it down occasionally to a pitch at which it was scarcely audible. After a few weeks I ceased to employ the chest register above

as I felt that beyond that point there was more effort than I at first realized. I had also begun to perceive that the less chest voice and the more head voice I used the better. I saw no improvement whatever in the chest voice, but the head voice from

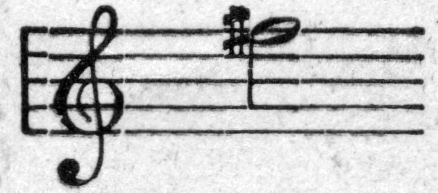

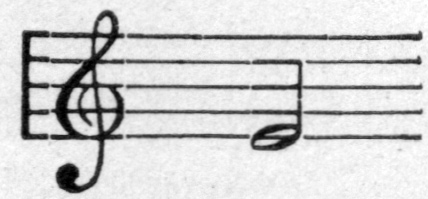

upwards was gaining strength to a remarkable extent. But two or three weeks later I was surprised one morning to find myself using, at about this pitch

a voice which I was not aware that I possessed. It sounded like chest voice, but when I came to examine it I found that it was produced in the same way as the head voice. This was a most astonishing revelation to me, because I knew quite well that, before I commenced my training, I had no voice whatever at that pitch, except in the chest register. Here, then, was an entirely new voice, created apparently out of nothing—a voice which, to describe it in plain though unscientific terms, had the chest tone without the chest production. It was a plain indication of the manner of nature’s working in the evolution of the adult male voice, and its bearing upon the whole question of voice-production was to my mind unmistakable. Of course, I spoke to my teacher about it, but he was not disposed to agree altogether with the interpretation which I put upon the matter. It led, however, to my making still more use of the head voice and, with his approval, restricting the chest register to a few notes at the bottom of my compass. In this way I ultimately succeeded in developing a light tenor voice, which, when heard at its best, was readily mistaken for the discarded chest voice, though, besides being of much better quality, it was, of course, incomparably easier to produce and of far greater upward range.

But I have made experiments with other and much better voices than my own, and the result of some of these experiments has been fully to corroborate these views. In one case in particular in which the voice was of a decidedly robust nature, the transformation was so complete that the new kind of chest voice evolved out of the so-called falsetto was not only quite as powerful as the chest voice which it superseded, but was as firm and strong at the very bottom of the compass (right down to G on the bottom line of the bass staff) as it was in any other part.

[The final article upon this subject will appear in another issue.—Editor.]