Remarkable career of one of the most influential musicians of the past century

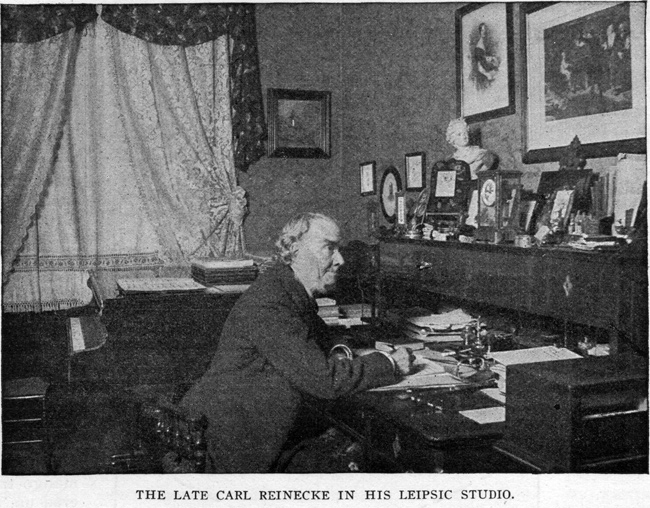

In the last issue of The Etude there appeared what was doubtless the last article of Prof. Dr. Carl Reinecke, the eminent pianist, composer and musical educator, who died in Leipsic on March 10.

In that issue we also called the attention of our readers to the remarkable virility of the author of the article. Although conservative in its tendencies, the article itself was treated with all the freshness and interest of a youthful writer.

Reinecke was born at Altona, Germany, July 23, 1824. Reinecke’s father was a musician, and, although he had no intention of training the boy to become a professional pianist, he gave him regular instruction for several years, with the result that when only eleven years old Carl Reinecke played before King Christian of Denmark in such a creditable manner that the latter gave him a stipendium, which enabled him to go to the city of Leipsic for three years’ study. According to Grove he was also an excellent orchestral violinist in his youth.

Reinecke was born at Altona, Germany, July 23, 1824. Reinecke’s father was a musician, and, although he had no intention of training the boy to become a professional pianist, he gave him regular instruction for several years, with the result that when only eleven years old Carl Reinecke played before King Christian of Denmark in such a creditable manner that the latter gave him a stipendium, which enabled him to go to the city of Leipsic for three years’ study. According to Grove he was also an excellent orchestral violinist in his youth.Reinecke had the privilege of knowing both Schumann and Mendelssohn in the Saxon city. His recollections of these great masters appeared in The Etude for December of last year. Quoting from this memorable article, we come to the following interesting passages:

“When I appeared the second time, fully prepared to hear a crushing verdict upon my work, he (Mendelssohn) received me so warmly that I felt at once at ease. He astonished me greatly by playing several passages from my quartet which had particularly pleased him; as well as others with which he found fault. When I returned to my room I immediately wrote down all that the great master had said to me in a letter to my father, in order to lose none of his golden words either of praise or censure. Many years afterward I found the letter among my father’s papers, so that I am now in the fortunate position of being able to quote Mendelssohn’s words exactly. They were:

” ’ … You must be more exacting with yourself; you must write no measure that is not interesting in itself; but do not become so critical that you cannot accomplish anything at all. Your playing is faulty in that you play too much en gros (on a large scale); you need to enter more closely into the finer details of the work—but then en gros again. Be industrious, young man. You have youth, strength and talent as well. To be sure, even now you will find plenty of admiration and flattery at all the tea-parties of Hamburg and also of Leipsic, but that sort of thing helps no one. There is no lack everywhere of flatterers, but there are never enough of earnest artists, and you have it in you to become one—you have only to choose. However, no young artist like you should ever commit the error of ever publishing a whole book of songs every one of which is in triple measure.’”

Reinecke’s lessons with Schumann were even fewer than those with Mendelssohn, but he enjoyed the society of both illustrious men. After completing his work at, Leipsic he made several tours through different parts of Europe, meeting with especial success as a performer of the works of Mozart. During his life he was generally recognized as the great exponent of Mozart. In 1851 Hiller secured the position of instructor in pianoforte playing at the Conservatorium of Musik at Cologne. In 1854 Reinecke became director of the orchestra and of the conservatory at Barmen (Germany). In 1859 he became the musical director of the University of Breslau.

THE GEWANDHAUS ORCHESTRA.

With the death of Mendelssohn (November 4, 1847) the Leipsic Orchestra came under the direction of N. W. Gade. One year later Julius Rietz succeeded Gade. In 1860 Rietz removed to Dresden and Reinecke succeeded him as director of what is doubtless the world’s most famous orchestra. In the same year he became professor of composition at the Conservatory. He held the position of director of the Gewandhaus Orchestra for thirty-five years. During this time he made occasional tours and was received with especial favor in England as a virtuoso and as a pianist. When he resigned from the directorship of the orchestra, in 1895, he retained his position at the Conservatory, and two years later he was appointed director of the institution, and held this position until his resignation in 1902.

HIS EDUCATIONAL WORK.

Reinecke’s fame will doubtless rest largely upon his work as an educator. No teacher has ever had more famous pupils, with the possible exception of Franz Liszt. In The Etude for January, 1908, he contributed an article upon his many celebrated pupils. Among his best-known pupils were Edvard Grieg, Max Bruch, Hugo Riemann, R. Joseffy, G. W. Chadwick, J. E. Perabo, Sir Arthur Sullivan, Karl Muck, Felix Weingartner, Samuel L. Hermann, Dr. Paul Klengel, Oscar Paul, Teichmüller, Prof. Heinrich Zöllner, Rudorff and many others. Grieg’s iconoclasm in matters of musical education led him to assail the methods of Reinecke and Plaidy. Reinecke felt this attack very bitterly, and in the article above mentioned he states: “I can say that this is the only saddening experience I have ever had in connection with any of my pupils.”

REINECKE AS A COMPOSER.

In order that The Etude readers may obtain a fair estimate of the standing of Reinecke as a composer we are quoting the following from the revised edition of “Grove’s Musical Dictionary,” which is recognized as the standard musical lexicon of our times:

“Reinecke’s industry in composition is great, his best works, as might be expected, being those for the piano. His three-pianoforte sonatas are excellent compositions, carrying out Mendelssohn’s technique without indulging the eccentricities of modern virtuosi. His pieces for the two-pianoforte are also good. His pianoforte Concerto in F sharp minor, a well-established favorite both with musicians and the public, was followed by two others in E minor and C major, respectively. Besides other instrumental music, a wind octet, quintets, four string quartets, even trios, concertos for violin and violoncello, etc., he has composed an opera in five acts, entitled King Manfred, and two in one act each, Der Vierjahrigen Posten and Ein Abenteuer Handel’s; incidental music to Schiller’s William Tell; an oratorio, Belsazar; cantatas for men’s voices, Hakon Jarl and Die Flucht nach Ægypten; overtures, Dame Kobold, Aladdin, Friedensfrier and Zenobia; a funeral march for Emperor Frederick, two masses, three symphonies and a large number of songs and piano pieces in all styles, including valuable studies and educational works. Of his settings of fairy tales for female voices, Schneewitschen, Domröschen, Aschenbrödel and several others are very popular. His style is refined, his mastery over counterpoint and form is absolute, and he writes with peculiar clearness and correctness.”

HOME LIFE OF REINECKE.

The simple, kindly nature of Reinecke is finely told in the following selection from Louis C. Elson’s genial and witty “European Reminiscences”—which is, by the way, one of the most fascinating and entertaining books ever written upon travel abroad:

“Capellmeister Reinecke in himself illustrates the modestly great character of the German musicians of rank. He has no tremendous salary; he does not dictate royal terms for every appearance of himself and orchestra; but he is sincerely honored by everyone in Leipsic, and in his autograph album are letters of heartiest recognition from Schumann and Berlioz down to kings and queens. It is, however, no longer a combination of poverty and honor for the musicians in Germany. Mozart’s day of suffering is past. An eminent professor at Leipsic told me that the high prices paid in America are having their influence in Germany. The great institutions find that if they wish to keep the musicians from starting for the New World they must give pecuniary inducements to stay in the Old.

“I had some charming glimpses of the home life of Capellmeister Reinecke, as he took me from the Conservatory to his modest quarters in the Querstrasse, somewhat nearer the sky than some of our less learned native composers dwell. A number of charming young ladies of assorted sizes greeted my view in the drawing room, and I was presented, one by one, to the daughters of the Capellmeister. Astounded at the rather numerous gathering, I ventured to ask whether any had escaped, and was informed that some of them had—into the bonds of wedlock. The sons, too, seemed especially bright, and the wit and badinage around the dinner table was something long to be remembered. Reinecke has not got the American fever to any extent, and a very short sojourn showed me why he is not anxious to change his position for one in the New World. It is true that he has not a salary such as our directors and conductors of first rank obtain, but on every side were tokens of friendship and homage from the greatest men and women of Europe, and when, the next day, he took me to his Kneipe near the Conservatory, I noticed that everyone in Leipsic took off his hat to the simple and good old man; everyone, from nobleman to peasant. It counts for something to be thus honored and beloved, and perhaps a few thousand dollars would not compensate for the loss of such friends.

ASSISTING AN ARTIST.

“How kindly and paternal Reinecke is may be clearly shown by relating the origin of the beautiful violin part to the song, ‘Spring Flowers.’ He had composed this without any violin obligato whatever, and it was to be sung by a young lady at her début in a Gewandhaus concert. The evening before the concert the artist came with a decided fit of the ‘nerves’ to Reinecke’s home, and, in trembling and tears, expressed her forebodings for the debut of the morrow. The good-hearted composer sat down to think matters over, and then exclaimed, ‘I will give you some extra support for the voice so that you cannot fail,’ and then wrote the violin part, which is so tender and characteristic. Immediate rehearsal followed, and, thanks to the violin support and the goodness of Reinecke, the début was a success. And at the Kneipe, too, I saw how much of contentment, passing riches, there was in such an artist life, for here in the corner of a very modest Wirthschaft were gathered some of the greatest art-workers of Leipsic (literature and painting were represented, as well as music), and every day at noon they met and spoke of their work, their hopes, their plans and their arts; in such an atmosphere the plant of high ideality could not but thrive, and I could only wish that we might some day have such unostentatious and practical gatherings among the artists of America.”

REINECKE’S ASSISTANCE TO “THE ETUDE.”

Reinecke rendered valuable assistance to The Etude through many extremely important articles. He was a good friend of the publisher and frequently showed his sympathy and interest in this journal and in American musical education. His contribution to The Etude of December, 1909, ended thus:

“In closing, I wish to thank the editor of this magazine for giving me the opportunity of gossiping over a period of my life now far in the past; it has been a pleasure indeed, and I have been deeply moved as I have let the many letters written by Schumann, now yellowed by time, glide through my fingers in order to choose from them those best fitted to complete my task. And I might add that it would be an especial gratification to me if these random, unadorned reminiscences of mine should aid in altering the heretofore one-sided view of me taken by my American friends; instead of looking upon me merely as the good uncle who writes pleasing songs and piano pieces for the young people, let them consider my numerous orchestral and chamber music works; my many songs, both secular and sacred; my piano concertos, etc., etc.”

Notwithstanding this last wish of an eminent musician, Reinecke is likely to be best known by the compositions which are more readily playable, such as those in his Juvenile Album, Sketches in Tone and his Characteristic Sketches.

Our readers possessing files of back numbers of The Etude may desire at this time to refer to a few of the many excellent articles Reinecke has contributed to this journal. We give the following list:

“The Scale in Modern Music.” April, 1910.

“Schumann and Mendelssohn.” December, 1909.

“My Pupils and Myself.” January, 1908.

“A Newly Discovered Sketch by Mozart.” April, 1908.

“The Works of Robert Schumann.” December, 1906.

“Some Noted Musicians.” May, 1906.

“Heller’s Writing Desk.” January, 1904.

“How Beethoven Worked.” April, 1904.