Selected and arranged for ETUDE readers from an excellent symposium which appeared recently in the London Musical Times.

Chopin had little fondness for the English people and for England. In fact, upon one occasion while returning from that country to Paris he is reported to have said to a companion: “Do you see the cattle in this meadow? They have more intelligence than the English” (“Ca a plus d’intelligence que les Anglais”). England, however, is too broad to consider the thoughtless complaints of a neurotic invalid who lived most of his life on the flattery and superficiality of the gayest of European capitals. Throughout his whole existence Chopin had been the pampered pet of a favored few who had the artistic foresight to divine his indescribable genius. Chopin is exceptionally popular in England, as in America. The London Musical Times, one of the foremost English musical journals, which is now in the fifty-second year of its existence, has recently printed the following excellent symposium, giving the opinions of great musicians of the past and present upon Chopin.

Chopin had little fondness for the English people and for England. In fact, upon one occasion while returning from that country to Paris he is reported to have said to a companion: “Do you see the cattle in this meadow? They have more intelligence than the English” (“Ca a plus d’intelligence que les Anglais”). England, however, is too broad to consider the thoughtless complaints of a neurotic invalid who lived most of his life on the flattery and superficiality of the gayest of European capitals. Throughout his whole existence Chopin had been the pampered pet of a favored few who had the artistic foresight to divine his indescribable genius. Chopin is exceptionally popular in England, as in America. The London Musical Times, one of the foremost English musical journals, which is now in the fifty-second year of its existence, has recently printed the following excellent symposium, giving the opinions of great musicians of the past and present upon Chopin.

Following a short biography in which it points to the fact that the date of Chopin’s birth has been established with reasonably good authority as occurring on February 22, 1810, and not in 1809, as is frequently stated, the opinion of Joseph Elsner, Chopin’s teacher, is given. When Chopin was only a child Elsner said of him:

“Leave him in peace; his is an uncommon way because his gifts are uncommon. He does not strictly adhere to the customary method, but he has one of his own, and he will reveal in his works an originality which in such a degree has not been found in anyone.”

Chopin’s opinion of his two and only teachers was expressed later as follows:

“From Zwyny and Elsner even the greatest must learn something.”

In 1831 Chopin went to Paris and met Kalkbrenner, who was then a famous pianoforte teacher, only to decide not to study with him. After much success as a performer he heard Field, who was a forerunner, but scarcely, in any sense, an instructor of Chopin. Field’s opinion of Chopin was that he was “un talent de chambre malade” (a genius of the sick-room), a criticism which (as Professor Niecks says) makes one think of Auber’s remark that Chopin was dying all his life. Berlioz and many other contemporary musical lights were now in Chopin’s circle. Yet, with all the aural experience he enjoyed of the best music of the period, he assimilated little or nothing that did not fit in his own idiom. His compositions now developed in boldness and originality, and he began to stir the critics. Rellstab, an eminent writer of the period, thus delivers himself of his feelings regarding the mazurka (Op. 7):

“In the dances before us the author satisfies the passion (of writing affectedly and unnaturally) to a loathsome excess. He is indefatigable, and I might say inexhaustible [sic], in his search for ear-splitting discords, forced transitions, harsh modulations, ugly distortions of melody and rhythm. Everything it is possible to think of is raked up to produce the effect of odd originality, but especially strange keys, the most unnatural positions of chords, the most perverse combinations with regard to fingering… .

“If Mr. Chopin had shown this composition to a master the latter would, it is to be hoped, have torn it and thrown it at his feet, which we hereby do symbolically.”

And Moscheles remarks:

“Where Field smiles, Chopin makes a grinning grimace; where Field sighs, Chopin groans; where Field shrugs his shoulders, Chopin twists his whole body; where Field puts some seasoning into the food, Chopin empties a handful of cayenne pepper. … In short, if one holds Field’s charming romances before a distorting concave mirror, so that every delicate expression becomes coarse, one gets Chopin’s work… . We implore Mr. Chopin to return to nature… .

“Those who have distorted fingers may put them right by practicing these studies; but those who have not should not play them—at least, not without having a surgeon at hand.

“I like to employ every free hour in the evening in making myself acquainted with Chopin’s studies and his other compositions, and find much charm in the originality and national colouring of their motivi; but my fingers always stumble over certain hard, inartistic, and, to me, incomprehensible modulations, and the whole is often too sweetish for my taste, and appears too little worthy of a man and a trained musician.”

In 1834, at Aix la Chapelle, Chopin met Mendelssohn for the first time. In one of his letters Mendelssohn thus writes of his new friend: “Chopin is now one of the very first pianoforte players; he produces as much effect at Paganini does on the violin, and performs wonders which one would never have imagined possible.” Leipsic was visited in 1835, and here there was a remarkable meeting with Mendelssohn, Schumann, Clara Wieck and other celebrities. Later Chopin met Thalberg, whom it is said he absolutely despised.

A TOUCHING INCIDENT.

After outlining the main epochs of Chopin’s interesting life, the Times relates the following interesting facts pertaining to the death and burial of Chopin:

“His health now rapidly failed, and on October 17 he passed away. Liszt, who saw Chopin soon after his decease, states that his face, which had previously borne the expression of his suffering, now resumed a look of youth, purity and calm. An impressive funeral ceremony, at which Mozart’s ‘Requiem Mass’ was performed, was held at the Church of the Madeleine, and the burial took place at the cemetery of Père la Chaise, Meyerbeer and other mourners walking the whole three miles bareheaded. A touching incident was the sprinkling on the coffin, when in the grave, of Polish earth which, enclosed in a silver cup, had been given to Chopin nineteen years before by friends on his departure from Wola.”

CHOPIN’S PLAYING.

Regarding Chopin’s playing and his method of composition, the writer in the Times states:

“Berlioz said that Chopin could not play strictly in time, and Sir Charles Hallé related to Professor Niecks an account of a dispute between him (Halle) and Chopin as to whether the latter played his ‘Mazurka’ in four-four instead of three-four time, and although Chopin was at first reluctant to admit the change, he was ultimately convinced. One cannot help remarking that in the indefiniteness of rubato many of the performers of Chopin’s music leave the composer entirely in the shade. Dr. Hadow, in his second series of ‘Studies in Modern Music,’ points out that the tonality of Chopin’s music was to some extent affected by that of Polish folk-songs, which are often written in one or other of the ecclesiastical modes.

“We read that Chopin was very fastidious in his method of composition. He would spend weeks in writing and rewriting a single page. How much more fluent and confident are even some of our youngest composers in these advanced times!”

EMIL SAUER’S OPINION.

Emil Sauer, considered throughout the entire musical world as one of the very greatest virtuosos since the time of his famous teacher, Franz Liszt, writes as follows:

“When you ask what Chopin and his immortal works mean to me, I find mere words inadequate to the full expression of my feeling of almost reverential appreciation of that great master. While I am seated at the pianoforte, he is ever my inspiration. Of all the gods who have showered countless jewels on our pianoforte literature, he remains the one at whose shrine I ever tender heartfelt thank- offerings on bended knee. ‘Doux et harmonieux génie!’—graceful and deserved tribute paid to Chopin in the opening of Franz Liszt’s noble biography of the musician. That tribute finds its echo in my heart. ‘God of the Pianoforte,’ Rubinstein fittingly calls him in his work, Die Kunst und ihre Meister. Never was the language of praise, albeit with flowery epithets, more justly applied than to the genius of Chopin, the dreamy Minnesinger, who, now sobbing with passion, now mourning for his country, and again vibrating with melodies worked up to a wild enthusiasm, has brought delight and happiness to millions.

“In the greater forms of musical expression (pianoforte concertos, works in variation form, etc.) Bach, Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann alone surpass him. As tone-poet, master of color and creator of sound-effects—such effects as were completed and considerably extended by Franz Liszt— no one else comes near him. In vain you seek his equal. Works, full of attractive melody, like his preludes, nocturnes, impromptus, etudes, ballades, scherzos, waltzes and polonaises, stand alone and unchallenged. The depth and tragedy, too, which speak to us from the two sonatas, the F minor Fantasia, the Barcarolle, the Polonaise-Fantasia, etc., are typical of the skill, the power and the ‘infinite variety’ of the great composer.

“For a proper interpretation of Chopin’s muse, and a complete understanding of his inner meaning, we must not look to the traditional pianists, but to those whose tastes are cosmopolitan, their perceptions acute, their manners polished and their powers of expression cultivated and refined. In short, the true exponent of Chopin’s work must be one to whom music is not a science, but an art; who produces his music, not with, studied calculation and mechanical intelligence, but with that heartfelt earnestness which distinctly marks the true virtuoso.

“Unfortunately, the number of those who count it no penance to play in public, who idolize their pianoforte and lovingly caress its keys, making them speak in clear, bell-like tones, is extremely limited. They are the ‘peculiar faddists’ (wunderliche Käuze) who, through a single mishap in a whole evening, an overstrong accent, or a pause too short, have a sleepless night. No composer demands more careful treatment in his works, round which are woven artistic arabesques like garlands of flowers, than does Frederick Chopin. The adequate interpretation of his compositions requires extreme accuracy, subtle handling and loving care of each individual note, with a true sense of sound and color, accompanied by an artistic freedom in performance, aided by the possession of a faultless technic. For this reason, those who master the pianoforte ‘as musicians rather than as pianists’—a new phrase, but rapidly growing in popularity—suffer disastrous shipwreck on the rocks concealed in Chopin.”

PROFESSOR NIECKS’ OPINION.

Although Professor Niecks was born at Dusseldorf, in Germany, his work has been so closely connected with musical life in Great Britain that one rarely thinks of him otherwise. He is now the Professor of Music at the University of Edinburgh. He is an authority upon the life of Chopin. To the Times’ symposium he contributes the following:

“Chopin is undoubtedly one of the most exquisitely poetical musicians the world has seen, and if the stress is laid on ‘exquisitely’ and the qualification ‘romantic’ added, it may be unhesitatingly said that he was not only one of the most, but, indeed, the most poetical musician the world has seen. His superiority among the post-classical composers for the pianoforte as to originality and beauty of style and matter is universally recognized. The influence exercised by him on music generally is, on the other hand, too much overlooked. He was a creative and inspiring power not merely in pianism, but also in music at large. To be convinced of this we have only to realize the difference between Chopin’s harmonic sources and kind and degree of expressiveness, and those of his predecessors. Original as Schumann was, he was greatly influenced by Chopin. On Liszt the latter’s influence was, of course, much more powerful, for Liszt’s originality as a composer was less, and his familiarity with his fellow-pianist’s compositions greater. But Wagner, too, must have been strongly influenced by the Polish master, whether directly or indirectly does not matter. No doubt the chromatic in the texture and the psychological and intimately subjective may be said to have been in the air at that time; but Chopin was indisputably the first to give a strong impulse in that direction.

“Chopin owed much to Poland—to the country and the people, and the folk-songs and folk-dances; but Poland owes infinitely more to him. Although a patriotic Pole, he was not an average nor a typical Pole. Nations imagine that they produce their geniuses. That, however, is mere foolish self-complacency and vaingloriousness. Geniuses are gifts. Poland had as little to do with the making of Chopin as Italy, England and Germany had with the making of Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe. Genius is the result of a felicitous but fortuitous concurrence of circumstances.

“Chopin’s pianoforte style is as such an ideal style—the nature of the instrument and the nature of the style are coextensive. This could not be said of Liszt’s pianoforte style, which is more many-sided, but less pure. Chopin’s piano style is also a virtuoso style. Virtuosity, however, is there as a means to a higher end, not for its own sake. No pianist-composer’s music is so much played as Chopin’s, and no composer’s music is so rarely well played. In fact, if the present state of things prevails much longer, the public must lose its belief of Chopin as the most poetic of pianist-composers.”

TOBIAS MATTHAY’S OPINION.

Tobias Matthay is well known in England as a pianist and as the author of an exhaustive work upon the study of pianoforte touch. He was born at Clapham, England, in 1858, and is now one of the professors of pianoforte playing at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Regarding Chopin he says:

“Chopin’s success in making his musical and poetic invention synchronize so perfectly with the acoustical and mechanical possibilities of his instrument must be attributed, in the first place, to his infinitely fine musical ear, which forbade his writing the inappropriate.

“It is difficult to determine exactly how far his own particular ways of key-treatment (touch or technique) influenced his invention, or how far his poetic feeling compelled him to gain his particular playing-technique, but the results are clear enough. The more salient features of the pianistic progress he wrought are found in the enormously greater delicacy and variety of tone he demanded in his cantabiles, the musicality and often the extreme lightness of his passage-work, and the laying-out of this in note-groups beyond the octave limit, and his extensive use of chromatic passing-notes; and, perhaps more notable still than these points, his revelation of the immense possibilities of the rubato element, and his constant but subtle use of the damper-pedal.

“With regard to his cantabile no doubt his invention was here greatly influenced by his own technical habits. From the internal evidence of his music, the remarks of his pupils and the shape of his hand, it is conclusively proved that he well knew the use of what we now term ‘flat finger’ weight- touch, a singing tone produced by a perfectly elastically used finger in conjunction with release of the whole arm, thus admitting far greater beauty and variety of singing tone than that of the earlier touch methods. Again, his own playing clearly influenced his passage invention, a passage-technique quite original as regards a lightness and swiftness before undreamt of, as, for instance, in so many of his wonderful filigree cadenzas—a lightness obviously to be attributed to his having thoroughly mastered those problems of key and muscle which we now sum up under the heading of ‘agility touch.’ We may admit that these improvements in pianoforte treatment had been in a measure led up to by earlier composers, yet Chopin leapt leagues ahead of them.”

FREDERICK CORDER’S OPINION.

Frederick Corder is one of the ablest of living English writers and composers. He was born at London in 1852, and was the “Mendelssohn Scholar” of the Royal Academy of Music in 1875, and is now curator of the same institution. His works on musical theory are greatly admired. Of Chopin he writes:

“It has always seemed to me that Chopin has not yet received adequate recognition as harmonist. Until about a generation ago he was looked upon with something like contempt by those fine-crusted old musicians like my teachers, Hiller and Macfarren, both of whom openly declared that music had said its last word with Mendelssohn. Even the broad-minded Prout only ventured to give two insignificant illustrations from Chopin in his harmony book. Theorists regarded him as a writer of elegant drawing-room music on the same plane as Henselt, but addicted to a sad misuse of those hateful chromatic chords. The people who could only play his easiest nocturnes and the A minor valse used to cry fie! upon him for being so sentimental, forgetting that these pieces were just the ‘pot-boilers’ by which he won the affections of the pianists. Now I come to think of it, when I played the F minor Fantasia at my examination for the Mendelssohn Scholarship in 1875, there was only one English musician—Arthur Sullivan—out of a committee of fifteen who knew anything of the work.

“Chopin arrived at a fortunate time. The romantic tendency in music, initiated by Spohr and Weber in opera, was beginning to make itself felt in abstract music. In an incredibly short space of time the diatonic track of Mozart and Beethoven was obliterated by the chromatic experiments of Schumann, Liszt and Wagner. Incited by their example, Chopin distanced all his contemporaries in the ease with which he manipulated the new progressions, and especially in the marvelous grace with which he crowned them with melody.

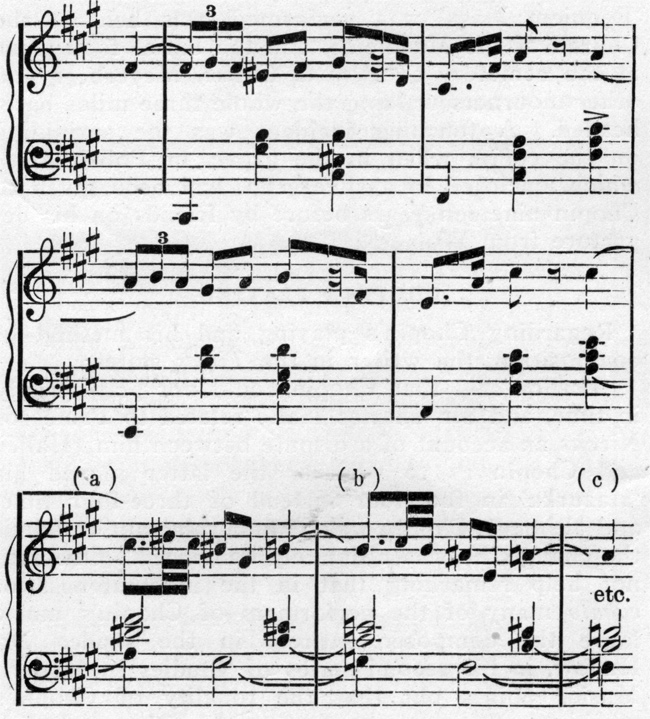

“However intricate the harmonic web, Chopin’s melody never lacks charm—charm of a tender and always refined kind. Austerity was a mood he never knew. From the marvelous mazurkas to the great ballades you can find no page that is not absolutely attractive. It is interesting to compare his Op. 1—a Humoreske Rondo—with the later works and to note how quickly the chains of dominant sevenths and Spohr-like progressions of diminished sevenths on a dominant pedal were abandoned in favor of combinations of the two which appeared magically novel. The very first of the mazurkas had such a passage on the measures marked A, B and C:

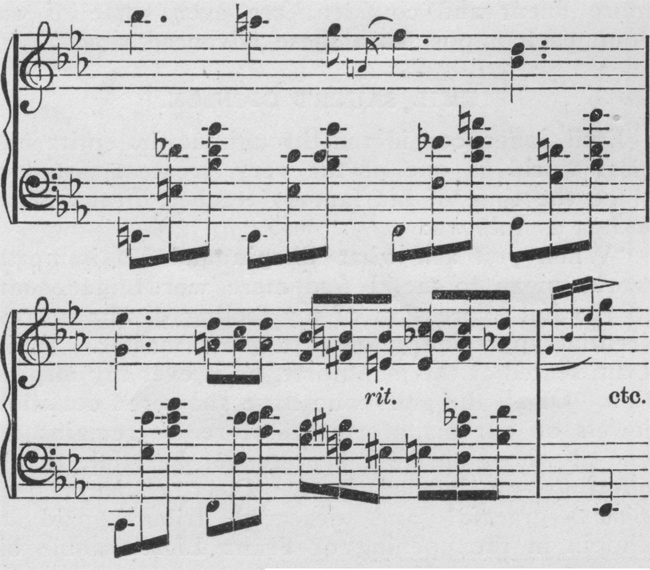

“He alone possessed the secret of these progressions, so natural, so obvious to us now, yet which no one has successfully imitated. In the E flat Nocturne no familiarity can rob that return from the dominant key of its delightful flavor:

“In the same vein, but yet more romantic, is the return to the subject in the slow movement of the B minor Sonata:

“One might quote dozens of examples as striking as these, yet all different: the B flat major Prelude, with its ingenious chromatic accompaniment figure; the majestic C minor Polonaise, with its theme in the bass and resultant strange harmonic effect; the unparalleled pedal point in the Coda of the Barcarolle; but perhaps above all the amazingly original first Scherzo in B minor. It is not generally known that this piece was published under the title of ‘Le Banquet Infernal,’ a title which proved too shocking for the drawing-room. But it explains the weird character of the piece, and those terrific augmented sixth chords on the last page. The demoniac character given by the passing-notes in the arpeggio passages is wonderful, and the peaceful middle section (usually exaggerated out of all sense by performers) is in the highest degree artistic.

“Towards the end of his life Chopin recognized more clearly the power which a real mastery of counterpoint bestows. That a man could exhibit such endless variety of invention in such unpromising ground as the mazurka and polonaise afford is to my mind the highest evidence of his greatness.

“I could discourse for pages on his codas and concluding cadence alone; but it is needless when their beauties are at everyone’s reach. It is a very superficial remark to say that Chopin is sentimental: all chromatic progressions convey a greasy, sickly impression; but can the writer of the A flat Polonaise, the first and third Scherzos, the Allegro de Concert and many such dashing compositions be adequately described by such an epithet? Surely not.”

VINCENT D’INDY’S OPINION.

The eminent French composer writes of Chopin, in his “Cours de Composition Musicale,” Book II, first part, as follows:

“With Chopin’s work we perceive what has been since called the pianistic style, a style of which the effects were, and still are, in many ways deplorable. All the compositions for pianoforte which up to now we have examined remained, in fact, exclusively musical, whether signed Bach, Rameau, Haydn, Beethoven or even Schubert: that is to say, the legitimate care for instrumental effect was always subordinate to the claims and exigencies of music. During the romantic period, however, we pointed out the growing influence of the concerto style, manifesting itself principally by the unusual extension of the trait agogique, or touch of virtuosity, serving as conclusion to the first exposition in movements of the sonata type. Through that, two very serious errors crept into pianoforte music, of which Chopin exaggerated the effects in proportion to his insufficiency of genuine musical education: 1. Notes selected for advantageous fingering, and not for the architectural logic of the work. 2. Entire passages written solely for virtuosity, and playing no useful role in the balance of the composition.