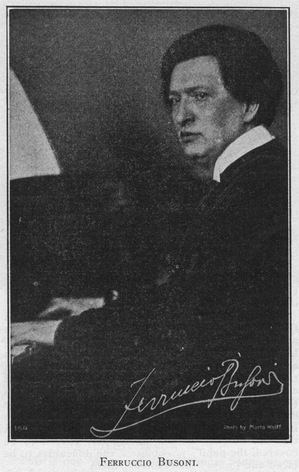

From an interview secured expressly for THE ETUDE from the eminent virtuoso

FERRUCCIO BENVENUTO BUSONI

[Editor’s Note.—There is something particularly interesting in the recent and pronounced successes of Ferruccio Busoni in America which should be of greatest encouragement to those who have striven to succeed and who have imagined that their inability to compel immediate success can only be classified as failure.

Busoni has always been recognized as an artist of great gifts and unquestioned artistic ability. It was, however, not until the present season, that American audiences have been forced to realize that in Busoni we now have one of the very greatest virtuosos of our time. His recent success is the result of development and a realization of early deficiencies. Busoni has never stopped in his effort to improve.

He was born at Empoli, near Florence, in 1866. His father was a clarinetist and his mother (maiden name Weiss) was an excellent pianist. His first teachers were his parents. So pronounced was his talent that he made his debut at the age of eight in Vienna. He then studied in the Austrian city of Graz under W. A. Remy (Dr. W. Mayer). In 1881 he toured Italy and was made a member of the Reale Accademia Filarmonica, at Bologna. In 1886 he went to reside in Leipsic. Two years later he became teacher of pianoforte at the Helsingfors (Finland) Conservatory.

In 1890 he captured the famous Rubinstein prizes for both pianoforte playing and composition. In the same year he became professor of pianoforte playing at the Moscow Imperial Conservatory. One year later he accepted a similar position at the New England Conservatory at Boston. Three years later he returned to Europe and engaged in a very successful tour as a pianist.

Seven years ago he returned to America and made a most favorable impression upon music critics everywhere. He then accepted the position of director of the Meister Schule for piano at the Imperial Conservatory in Vienna. His present tour commenced in January and the revelation of his matured artistic abilities—the result of ceaseless practice and well-directed effort—have brought him triumphant success in all parts of the United States.

Busoni is now known as a virtuoso, but his compositions have been so numerous and so clearly indicative of his genius, that many declare that his future fame will rest largely upon his compositions.

Busoni’s works include over one hundred published opus numbers. His most pretentious work is doubtless his “Choral Concerto for Orchestra, Male Chorus and Pianoforte Solo,” which has been given abroad with very great success. His editions of the works of Bach give undisputed proof of his scholarship.]

“Some years ago I met a very famous artist whose celebrity rested upon the wonderful colored glass windows that he had produced. He was considered by most of his contemporaries the greatest of all makers of high-art windows. His fame had extended throughout the artistic circles of all Europe. A little remark he made to me illustrates the importance of detail better than anything of which I can think at present.

“He said, ‘If a truly great work of art in the form of a stained glass window should be accidentally shattered to little bits, one should be able to estimate the greatness of the whole window by examing (sic) one of the fragments even though all the other pieces were missing.’

“In fine piano playing all of the details are important. I do not mean to say that if one were in another room that one could invariably tell the ability of an artist by hearing him strike one note, but if the note is heard in relation to the other notes in a composition, its proportionate value should be so artistically estimated by the highly- trained performer, that it forms part of the artistic whole.

“For instance, it is very easy to conceive of compositions demanding a very smooth running performance in which one jarring or harsh note indicating faulty artistic calculation upon the part of the player would ruin the entire interpretation. As examples of this one might cite the Bach “Choral Vorspiel,” “Nun Freut euch,” of which I have made an arrangement, and such a composition as the Chopin Prelude Opus 28, No. 3, with its running accompaniment in the left hand.

“It is often perfection in little things which distinguishes the performance of the great pianist

from that of the novice. The novice usually manages to get the so-called main points, but he does not work for the little niceties of interpretation which are almost invariably the defining characteristic of the real artist—that is, the performer who has formed the habit of stopping at nothing short of his highest ideal of perfection.

LEARNING TO LISTEN.

“There is a detail which few students observe which is of such vast importance that one is tempted to say that the main part of successful musical progress depends upon it. This is the detail of learning to listen. Every sound that is produced during the practice period should be heard. That is, it should be heard with ears open to give that sound the intelligent analysis which it deserves.

“Anyone who has observed closely and taught extensively must have noticed that hours and hours are wasted by students strumming away on keyboards and giving no more attention to the sounds they produce than would the inmates of a deaf and dumb asylum. These students all expect to become fine performers even though they may not aim to become virtuosos. To them the piano keyboard is a kind of gymnasium attached to a musical instrument. They may of course acquire strong fingers, but they will have to learn to listen before they can hope to become even passable performers.

“At my own recital no one in the audience listens more attentively than I do. I strive to hear every note and while I am playing my attention is so concentrated upon the one purpose of delivering the work in the most artistic manner dictated by my conception of the piece and the composer’s demands, that I am little conscious of anything else. I have also learned that I must continually have my mind alert to opportunities for improvement. I am always in quest of new beauties and even while playing in public it is possible to conceive of new details that come like revelations.

“The artist who has reached the period when he fails to be on the outlook for details of this kind and is convinced that in no possible way could his performances be improved, has reached a very dangerous stage of artistic stagnation which will result in the ruin of his career. There is always room for improvement, that is the development of new details, and it is this which gives zest and intellectual interest to the work of the artist. Without it his public efforts would become very tame and unattractive.

SELF DEVELOPMENT.

“In my own development as an artist it has been made evident to me, time and time again, that success comes from the careful observance of details. All students should strive to estimate their own artistic ability very accurately. A wrong estimate always leads to a dangerous condition. If I had failed to attend to certain details many years ago, I would have stopped very far short of anything like success.

“I remember that when I concluded my term as professor of piano at the New England Conservatory of Music I was very conscious of certain deficiencies in my style. Notwithstanding the fact that I had been accepted as a virtuoso in Europe and in America and had toured with great orchestras such as the Boston Symphony Orchestra, I knew better than anyone else that there were certain details in my playing that I could not afford to neglect.

“For instance, I knew that my method of playing the trill could be greatly improved and I also knew that I lacked force and endurance in certain passages. Fortunately, although a comparatively young man, I was not deceived by the flattery of well- meaning, but incapable critics, who were quite willing to convince me that my playing was as perfect as it was possible to make it. Every seeker of artistic truth is more widely awake to his own deficiencies than any of his critics could possibly be.

“In order to rectify the details I have mentioned, as well as some I have not mentioned, I have come to the conclusion that I must devise an entirely new technical system. Technical systems are best when they are individual. Speaking theoretically, every individual needs a different technical system. Every hand, every arm, every set of ten fingers, every body and, what is of greatest importance, every intellect is different from every other. I consequently endeavored to get down to the basic laws underlying the subject of technic and make a system of my own.

“After much study, I discovered what I believed to be the technical cause of my defects and then I returned to Europe and for two years I devoted myself almost exclusively to technical study along the individual lines I had devised. To my great delight, details that had always defied me, the rebellious trills, the faltering bravura passages, the uneven runs, all came into beautiful submission and with them came a new delight in playing.

FINDING INDIVIDUAL FAULTS.

“I trust that my experience will set some of the readers of The Etude to thinking and that they may be benefited by it. There is always a way of correcting deficiencies if the way can only be found. The first thing, however, is to recognize the detail itself and then to realize that instead of being a detail it is a matter of vast importance until it has been conquered and brought into submission. In playing, always note where your difficulties seem to lie. Then, when advisable, isolate those difficulties and practice them separately. This is the matter in which all good technical exercises are devised.

“Your own difficulty is the difficulty which you should practice most. Why waste time in practicing passages which you can play perfectly well? One player may have difficulty in playing trills, while to another player of equal general musical ability trills may be perfectly easy. In playing arpeggios, however, the position of the players may be entirely reversed. The one who could play the trill perfectly might not be able, under any circumstance, to play an arpeggio with the requisite smoothness and true legato demanded, while the student who found the trill impossible possesses the ability to run arpeggios and cadenzas with the fluency of a forest rivulet.

“All technical exercises must be given to the pupil with great discretion and judgment just as poisonous medicines must be administered to the patient with great care. The indiscriminate giving of technical exercises may impede progress rather than advance the pupil. Simply because an exercise happens to come in a certain position in a book of technical exercises is not reason why the particular pupil being taught needs that exercise at that particular time. Some exercises are not feasible and others are inexpedient.

“Take the famous Tausig exercises, for instance. Tausig was a master of technic who had few, if any, equals in his time. His exercises are for the most part very ingenious and useful to advanced players, but when some of them are transposed into other keys as their composer demands they become practically impossible to play with the proper touch, etc. Furthermore, one would be very unlikely to find a passage demanding such a technical feat in the compositions of any of the great masters of the piano. Consequently, such exercises are of no practical value and would only be demanded by a teacher with more respect for tradition than common sense.

DETAILS OF PHRASING AND ACCENTUATION.

“Some students look upon phrasing as a detail that can be postponed until other supposedly more important things are accomplished. The very musical meaning of any composition depends upon the correct understanding and delivery of the phrases which make that composition. To neglect the phrases would be about as sensible as it would be for the great actor to neglect the proper thought division in the interpretation of his lines. The greatest masterpiece of dramatic literature whether it be “Romeo and Juliet,” “Antigone,” “La Malade Imaginaire” or “The Doll’s House” becomes nonsense if the thought divisions indicated by the verbal phrases are not carefully determined and expressed.

“Great actors spend hours and hours seeking for the best method of expressing the author’s meaning. No pianist of ability would think of giving less careful attention to phrasing. How stupid it would be for the actor to add a word that concluded one sentence to the beginning of the next sentence. How erroneous then is it for the pupil to add the last note of one phrase to the beginning of the next phrase. Phrasing is anything but a detail.

“Fine phrasing depends first upon a knowledge of music which enables one to define the limitations of the phrase and then upon a knowledge of pianoforte playing which enables one to execute them properly. Phrasing is closely allied to the subject of accentuation and both subjects are intimately connected with that of fingering. Without the proper fingers it is often impossible to execute certain phrases correctly. Generally, the accents are considered of importance because they are supposed to fall in certain set parts of given measures, thus indicating the metre.

“In instructing very young pupils it may be necessary to lead them to believe that the time must be marked in a definite manner by such accents, but as the pupil advances he must understand that the measure divisions are inserted principally for the purpose of enabling him to read easily. He should learn to look upon each piece of music as a beautiful tapestry in which the main consideration is the principal design of the work as a whole and not the invisible marking threads which the manufacturer is obliged to put in the loom in order to have a structure upon which the tapestry may be woven.

BACH, BACH, BACH.

“In the study of the subject of accentuation and phrasing it would not be possible for anyone to recommend anything more instructive than the works of Johann Sebastian Bach. The immortal Thüringian composer was the master-weaver of all. His tapestries have never been equalled in refinement, color, breadth and general beauty. Why is Bach so valuable for the student? This is an easy question to answer. It is because his works are so constructed that they compel one to study these details. Even if the student has only mastered the intricacies of the “Two Voice Inventions,” it is safe to say that he has become a better player. More than this, Bach forces the student to think.

“If the student has never thought before during his practice periods, he will soon find that it is quite impossible for him to encompass the difficulties of Bach without the closest mental application. In fact, he may also discover that it is possible for him to work out some of his musical problems while away from the keyboard. Many of the most perplexing musical questions and difficulties that have ever confronted me have been solved mentally while I have been walking upon the street.

“Sometimes the solution of difficult details comes in the twinkling of an eye. I remember that when I was a very young man I was engaged to play a concerto with a large symphony orchestra. One part of the concerto had always troubled me, and I was somewhat apprehensive about it. During one of the pauses, while the orchestra was playing, the correct interpretation came to me like a flash. I waited until the orchestra was playing very loud and made an opportunity to run over the difficult passage. Of course, my playing could not be heard under the tutti of the orchestra, and when the time came for the proper delivery of the passage it was vastly better than it would have been otherwise.

“I never neglect an opportunity to improve, no matter how perfect a previous interpretation may have seemed to me. In fact, I often go directly home from the concert and practice for hours upon the very pieces that I have been playing, because during the concert certain new ideas have come to me. These ideas are very precious, and to neglect them or to consider them details to be postponed for future development would be ridiculous in the extreme.

(This extremely helpful article will be continued in the next issue of The Etude.)