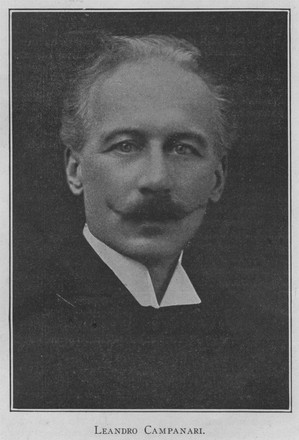

By LEANDRO CAMPANARI

Eminent Violin Virtuoso, Conductor and Teacher From an interview secured expressly for THE ETUDE

[Editor’s Note.—Leandro Campanari was born in Venice in 1859, on the 20th of October. He commenced his studies at a very early age, and so pronounced was his talent that he was sent by the city of Venice to the Musical Institute of Padua. At the age of 12 he toured Italy as a prodigy, his instrument being the violin. When 15 years old he entered the Conservatory of Music in Milan and studied the violin, harmony, counterpoint and conducting with the most eminent teachers of that institution. At 19 he graduated and went to England, where he made a pronounced success. He then toured Italy and France as a virtuoso. After this tour he returned to Italy and commenced his practical work as a conductor. In 1881 he came to America and made his debut as a soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, appearing also in many concerts throughout the United States. He returned to Europe, but came back to America, where he remained for three years as the head of the Violin School at the New England Conservatory of Music, in Boston. He also assumed the direction of the music at the Church of the Immaculate Conception and brought out many important sacred works for the first time in that city. After his service in Boston, Campanari returned to Italy and organized the Campanari String Quartet, which toured with great success for two years. During that time many composers of note, among them Puccini, Catalani, Sgambati, Bazzini, Vanbianchi, Frugatta, Bossi, Andreoli, composed music specially for the Campanari Quartet. He then became professor of violin playing at the Cincinnati College of Music, succeeding Schradieck, and remaining in that position for six years.

Then returning to Italy, he gave a series of symphony concerts at La Scala, and at the Lyric, in Milan, the cycle of Beethoven symphonies. (At one of these concerts Edvard Grieg was in the audience and at the end of the program warmly congratulated Campanari on his direction.) The orchestra then went on tour, meeting with pronounced success. The next important engagement of Campanari and his orchestra was in London, at the Imperial Institute, for a long and very successful season of nearly four months.

Three years ago he appeared in New York as one of the opera conductors of Hammerstein’s Opera Company. He also conducted the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra for a short time. With the same organization he has appeared in Reading, Trenton, Wilmington, Washington and Baltimore for performances of Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony.” He has also conducted in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Owing to the serious illness of his wife, an American lady and once a violinist of note, Campanari removed to California, but since her fortunate recovery Leandro Campanari has resumed his work as a virtuoso and a conductor. He has composed many English songs and three text-books for violin playing.

Leandro Campanari’s acquaintance with Verdi extended over a period of many years. As a youth he played in an orchestra conducted by the famous composer, and Verdi’s last work was first given under the direction of Campanari. The famous conductor’s brother, Signor U. Campanari, was one of the executors of the estate of Verdi, and few Italian musicians of to-day are in position to speak with greater authority upon the life of the foremost Italian musician since the days of Palestrina, Monteverde and Scarlatti.]

When the lives of the composers are viewed in the deceptive perspective of centuries so many entirely erroneous ideas become associated with them that it is well for those who have known our modern masters with any degree of intimacy to preserve their opinions in print. It is with great pleasure, therefore, thatI give to the readers of The Etude some recollections of the eminent master whom it was my good fortune to know personally.

In considering the life of Verdi one is first brought to the realization of the grand truth that genius must always triumph over all obstacles. Verdi’s father was a farmer, or peasant, and aside from a healthy body Verdi had none of those advantages of birth which frequently assist the young man in his fight for ultimate success. This he showed in his latter years. He was broad-minded in the extreme, dignified and tactful. He had many characteristics which remind me of Tolstoi. The simplicity of his tastes and habits of life remained with him to the end. It is true that he had an elegant apartment at a hotel in Milan, but he was happier when at work on his Villa of Santa Agata. Although he possessed all these characteristics, he could not be called a highly educated man in the broadest sense of the word. His culture was more along the particular line of music. It is difficult to express this without being misunderstood, as it is very difficult to conceive of a character of the towering talent of Verdi without associating with it the details of intellectual refinement that some people very stupidly confound with real worth and ability. In every other way he showed nothing of his peasant origin, and his triumph over the obstacles that beset his path are now a part of musical history.

His breadth is shown by the wonderful manner in which he kept step with the progress of the century. When he saw the enormous influence of Wagner and the self-evident worth of his ideas he was one of the first to recognize their potency as factors in the music of the future. Then he immediately sought to reconstruct his entire method of composition. Nothing more astonishing has occurred in the annals of art than the production of such operas as Otello and Falstaff by a composer who, during his entire previous lifetime, had been influenced by another and quite different style of composition. To the very end, however, he remained Verdi, and although the Wagnerian tendencies had the effect of broadening his work, they never removed or supplanted those characteristics which marked the style of the famous Italian master.

VERDI’S EARLIER YEARS.

It has been erroneously stated that Verdi was refused at the Conservatory of Milan because he did not give evidences of talent. This was not the case. As a boy he was wonderfully talented, but at the time he applied for admission to the Conservatory he had not had the technical training sufficient to enable him to pass the requisite entrance examinations. Milan’s admiration for the famous composer is happily indicated by the fact that the Milan Conservatory has been renamed the Verdi Conservatory.

Verdi’s development could not be called slow. His first operas showed signs of pronounced genius, but in everything he studied the times and wrote accordingly. The Verdi of the Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio, was very different from the Verdi of Falstaff. He was nothing if not tactful. He had great faith in the efficacy of opera as a means of educating the masses. In this my entire experience as a conductor has convinced me he was altogether right. I sincerely believe that the interest in music in America would be very greatly quickened if it were possible to have more operatic performances in our smaller towns in America. Musicians, alas! do not place themselves in the positions of those to whom they expect their music to appeal. How can the tired business man whose musical training has been decidedly limited hope to appreciate a Bach fugue or a Strauss tone-poem? In the case of opera it is very different. He is attracted by the Bohemian life in La Bohéme, he is enthused by the Spanish warmth of Carmen, he is mystified by Pelleas and Mélisande or entranced by the beauty of Tristan und Isolde. Few business men have the patience to read a work on philosophy or aesthetics, or even fiction, after eight long hours of eye-strain, but they can go to the theatre and look at æsthetical and philosophical problems when interpreted through the medium of representations of life as Ibsen, Hauptmann, d’Anunzio, Molière or Shakespeare have seen it. The opera in musical education is properly the forerunner of the symphony, the sonata, the fugue. Create a taste for music by serving it first in its most palatable form and the rest will follow. From many conversations with Verdi I am convinced that he held much the same ideas, since ninety per cent. of his attention was given to the composition of operas.

VERDI’S SINGULAR PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS.

I have said that Verdi was modest. Perhaps I should have said “retiring,” for he never coveted publicity. He was even imperious at times. When I was a boy of fourteen I played first violin in an orchestra at the first production of the now famous Manzoni Requiem. The performance was given under the direction of Verdi. At the end the Prefect of the city, an officer of high government importance, very courteously requested Verdi to give him the baton with which he had conducted the performance. Verdi turned to him indifferently and said: “Here, take it if you want it.” Invested as I was with the continental awe for authority and position, Verdi’s indifference to so important an officer made a big impression upon me. Upon another occasion Verdi and the great Italian statesman Crispi arrived at a railroad station at the same time. Verdi noted the awaiting crowd and was gratified, but when informed that those who assembled had done so partly in honor of Crispi he treated the latter with much coolness. It reminded me of the incident of Beethoven and Schiller meeting a noble personage. Schiller, with his court manners, bowed obsequiously. Beethoven, who never quite overcame the boorishness of his youthful surroundings, jammed his hat tight upon his head and walked away.

In Italy Verdi was regarded as little less than a god. During the war with Austria (1849-1859) the people wrote the magic letters V-E-R-D-I on the walls and the sides of public buildings in all parts of Italy. The meaning of this cabalistic sign was: Victor Emmanuel, Re d’ltalia (Victor Emmanuel, King of Italy). This was partly patriotism and partly a tribute to the great musical hero of Italy.

VERDI’S OPERAS.

Of Verdi’s operas much has already been said. Those of the so-called first period of his career as a composer show his latent talent in the making. Many of them deserve more frequent performance, particularly Mac- bet, Simon Boccanegra and Nabucco. It should be remembered that after the first performance of Nabucco the ladies of Italy, out of compliment to Verdi, wore green dresses on the following day—Verdi being in Italian “green” (verde). Of the operas of the second period Rigoletto, II Trovatore and Traviata are probably the most melodious, but there is much of great musical worth and decided dramatic interest in Les Vespers Siciliennes, Un Ballo in Maschero, La Forza del Destino, Macbet and Don Carlos. Of all the operas of this period my preference is probably II Trovatore. In this opera Verdi showed his remarkable melodic fecundity to a wonderful degree. No operatic melodies have ever made a greater impression upon the general public than have those of Trovatore.

Of those of the third period Aida is the most spectacular and pretentious. Otello is the most dramatic, and Falstaff ranks with Die Meistersinger as the greatest comic opera or humorous grand opera ever written. These three operas in themselves would have made any composer immortal. That they were written by a man who was past the age when many men feel that their life work is done, and that they are indescribably above anything Verdi wrote in his prime, must always remain one of the most astonishing facts in musical history.

No other composer has ever produced similar works at such an age, not even the immortal Richard Wagner, who was seventy years old when he died.

VERDI’S WEAKNESS.

Verdi wrote for the most part operatic works, but he had a fondness for sacred music, and among his last compositions were an Ave Maria, Pater Noster and a Stabat Mater. The Stabat Mater was his very last composition, and it was given to me to have the honor of rehearsing the music for the first time. These works have great musical value and some day will certainly be widely known.

He also made some attempts to write in other forms. Among his compositions was a string quartet. It was first given in Genoa by my quartet known as the “Campanari Quartet.” Verdi was terribly nervous over the performance and kept sending Ricordi, the publisher, numerous telegrams about the manner in which it should be rendered. Finally when it was performed in Genoa he was delighted with the work and embraced me at the end. It may seem ungracious, but I am forced to state that the quartet which Verdi regarded so highly falls very far below the great string quartets of some other masters and below Verdi’s greater operas in musical value. Verdi also painted pictures which he esteemed highly, but which were not of any considerable artistic significance. It seems somewhat odd that so well-balanced a man could be so mistaken as to his ability.

HOW VERDI WORKED.

Verdi invariably arose early in the morning and often worked until late at night. He was very fond of Nature and loved to work upon his farm. Natural beauties seemed to fill him with deep reverence and again great intellectual exhilaration. Often he would sit at his piano and play by the hour in search of effects. This was by no means an indication of musicianly weakness, but simply a method of musical exploration to find new tonal beauties lying in the bypaths of that wonderful thing we know as “inspiration.”

He would read the libretto he decided to work upon and then the musical thoughts would come to him so quickly that he could hardly write fast enough to put them down. It can only be described by the word “spontaneous.” Of course the more detailed development, scoring, etc., took more time and attention. When he found a new musical idea he would often call in his wife in order to find how his new-born thought would be received. Creative workers like to have audiences at their call. Molìère, the French dramatist, is said to have read most of his plays to his cook.

It is a mistake to believe that Verdi had nothing to do with the composition of his librettos. I am convinced that he must have given Boito many excellent ideas, for Verdi’s talent for the dramatic was very pronounced. Verdi was very fond of reading Shakespeare and also the Italian author Goldoni.

As I have said, Verdi had little love for personal display and was retiring at all times. His attire was always very simple. He dressed mostly in black, more rarely in dark blue. When called before the king he assumed no special court dress. He was always very neat and disliked slovenliness. He had very few friends, and among his one or two confidantes was Ettore Muzio, who taught singing in New York some years ago. Verdi was averse to hearing students sing, and always avoided such an appointment.

A BOX WITH A HISTORY.

When Verdi died he left a large box of manuscripts with the strict injunction that they were to be burned. My brother, who was one of the executors of the estate, executed this command without opening the box. What the great master desired to have destroyed no one knows. It is possible the box might have contained some really great masterpiece. We have noted that Verdi’s judgment was in error in the case of his paintings and his string quartet. Is it not possible that through a whim he may have deposited something in that box which would have proven as great as some of his other masterpieces? Alas! it is now long since devoured by flames and the world will never know what manuscripts Verdi desired to keep from it.

VERDI’S CHARITY.

Verdi’s munificent gift to Italy of a home for aged musicians, to which is devoted the income from the royalties of his operas, indicates his charitable intentions. Verdi was not ostentatious in his giving. He gave quietly and judiciously when he knew of musicians in need. He did comparatively little to encourage young musicians by giving them money. Perhaps he remembered the trials of his own youth and felt that the young man who had it in him to overcome trials had it in him to succeed, and the bigger the trials the bigger the success. Italy and all Italians love Verdi. He is as great a popular hero as the most illustrious man the country produced, and if Verdi was imperious to statesmen and politicians it was perhaps because he was conscious of the edifying fact that his name would be internationally famous when the officers of law, money, war and commerce have been totally forgotten. Long live Verdi, the greatest of Italian musicians of the nineteenth century!