From an Interview Secured Exclusively for THE ETUDE

By EDWIN HUGHES

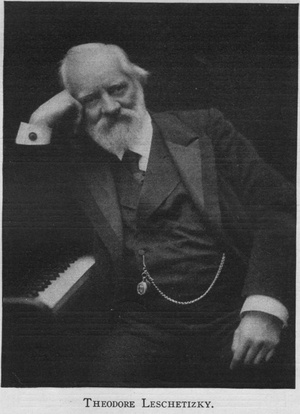

[Theodore Leschetizsky who will go down in musical history as the teacher of great virtuosos, is now seventy-eight years of age. He was born in Lancut, Austrian Poland, June 22d, 1830. His teachers were his father, who was in his time an eminent teacher in Vienna, Sechter and Czerny. He made very successful tours in 1848 and 1852 and thereafter became a teacher in the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and later he went to Vienna and became a private teacher. He has been married three times. His first wife was his famous pupil Essipoff. His other celebrated virtuoso pupils include Paderewski, Bloomfield-Zeisler, Gabrillowitsch, Katherine Goodson, Hambourg, Sieveking. In late years Leschetizky has given very few interviews similar to the following and as it is not likely that, from the nature of things, many other talks of the great master will appear we advise our readers to preserve this article.—Editor’s Note.]

[Theodore Leschetizsky who will go down in musical history as the teacher of great virtuosos, is now seventy-eight years of age. He was born in Lancut, Austrian Poland, June 22d, 1830. His teachers were his father, who was in his time an eminent teacher in Vienna, Sechter and Czerny. He made very successful tours in 1848 and 1852 and thereafter became a teacher in the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and later he went to Vienna and became a private teacher. He has been married three times. His first wife was his famous pupil Essipoff. His other celebrated virtuoso pupils include Paderewski, Bloomfield-Zeisler, Gabrillowitsch, Katherine Goodson, Hambourg, Sieveking. In late years Leschetizky has given very few interviews similar to the following and as it is not likely that, from the nature of things, many other talks of the great master will appear we advise our readers to preserve this article.—Editor’s Note.]

“AMERICANS PLAY TOO MUCH!”

Thus did Theodore Leschetizky express himself one bright Sunday forenoon when I sought him out in his Karl Ludwig Strasse Villa in Vienna for an interview on modern pianoforte study.

“How many come to me and say, ‘I practice seven hours a day,’ in an expectant tone, as though praise were sure to follow such a statement! As I say so often at the lessons, piano study is very similar to cooking,” with a hearty laugh.

“A good cook tastes the cooking every few minutes to see whether it is progressing properly; just so a piano student who knows how to study makes pauses constantly in his playing, to hear if the passage just played corresponded to the effect desired, for it is only during these pauses that one can listen properly.

“When I eat mushroom or tomato sauce I want to know that I am eating the one or the other. Some cooks there are who make concoctions which are neither one thing nor another—and they do not satisfy anybody when they come on the table.

“Nothing could better apply to pianoforte study than this comparison. A pianist must be an epicure—that is just the expression for it. He must taste, taste; not eat all the time. Out of four hours’ study, one who goes about his work properly will play perhaps only one-half of that time. The rest goes for pauses to think about what has gone before, and to construct mentally the following passage.

“This continual playing of a piece over and over again is not what I call study. When I want to learn a new piece I do not keep the notes in front of me on the music-rack; I throw them over this back on the top of the piano, so that I have to get up every time to look at them. After the image of the passage to be memorized is well in mind I sit down at the instrument and try to reproduce it—notes, touch, pedaling and all.

“Perhaps it doesn’t go the first time. Then I get up and take another look. This time I make a more strenuous effort—to avoid the trouble of having to stand up once more! This I call intelligent piano study. Learn a passage just once; afterwards, only repeat it.

“It is well to begin the study period in the morning with a few technical exercises—enough to get the hands into good playing condition. Afterward, alternate technic and pieces, so that the mind remains fresh, which is not the case when one works constantly at one or the other. In practicing exercises for strengthening the fingers one must not interrupt the work until the hand begins to feel the strain.

“It is like trying out a race-horse; if you want to see how fast and how far he can go, you must not stop him every moment. In practicing a trill you will find that you cannot continue for much more than a minute. By that time your fingers are well exercised; if you try to play longer your hand may drop off!”

So much is said nowadays about the mooted question of the “Leschetizky Method” (some even saying that Leschetizky has no method) that I took the opportunity to ask the master for his own views on the subject.

THE VALUE OF METHOD.

“Of course, in the beginning I have a method. A knowledge of correct hand position and of the many different qualities of touch which I use and which give a never-ending variety to the tone must be learned before one can go very far. The fingers must have acquired an unyielding firmness and the wrist, at the same time, an easy pliability in order to avoid hardness in the tone. Besides this, there are the rules for singing, which apply to melody playing on the piano to just as great an extent as to melody singing in the voice.

“The natural accents must be properly placed and long notes must receive an extra pressure in order to overcome the difficulty of sustaining tones on the pianoforte. All these things a good preparatory teacher can give as well as I, and for this reason I require my pupils to go first to an assistant, to the saving of both their time and money. Of course, the assistants are responsible to me.

“After pupils have once gotten this foundation they branch off in every direction; each has his peculiarities and no one method will answer for all any more; the teaching must become individual. The enforcement of strict rules cannot then be insisted upon. It is just as in law. Not everyone who kills his fellow-man is hanged or guillotined or electrocuted.

“There are always exceptions. Often circumstances arise which cause justice to yield, and just as we would not endure a dry, soulless justice, how much more reason there is that we should not have a dry, soulless art. There are many otherwise excellent pianists who play so however—exactly according to rule.”

“UNRIPE” STUDENTS.

I put the question of Americans coming abroad to study. Did not many come before they were ripe?

“Ach Gott!” was the reply, “one is always ripe to begin! And how many of those who come to me have to commence all over! Happily there are many good teachers in America nowadays—but then there are many bad ones, too. The situation is much improved since fifty years ago.

“Many a clarionettist or player of some other orchestral instrument wandered across the ocean only to find that he must have something else besides the clarionet to eke out an existence. What should he do? Give piano lessons, of course! The pupils of such musicians were bad enough, but when it came to their pupils”—Leschetizky ended the sentence with a smile and an expressive gesture.

About public appearance Leschetizky had some interesting things to say.

“For public playing the heart must be in the right spot, and there must be ‘nuances’ in the fingers. Tone and diction are everything. The pianist who knows how to tell a story in his playing is the one who holds the public. One must be constantly on the ‘qui vive’ to discover new and unexpected effects—whether they are beautiful or not they will always captivate an audience. Better it is, of course, when they are beautiful!

“When one plays in public one must consider the fact that he is in a larger field than the salon; more strength is needed, more breadth of effect required. I have to go back to the comparison with the cooking again! It is as though ten persons came to a dinner where only six were expected. In the cookbook one finds nothing to help one out of the dilemma, but a good cook must know how to get around the difficulty.

“There is too much banal piano-playing nowadays. I do not find that the art has developed in any way since the days of Rubinstein. No one plays to-day as he did!

“As for technical development, have the Alkan etudes or the Don Juan Fantasie grown any easier with time? The quantity of piano-playing has increased, yes, more strive for a great technic; but as for the quality I do not see any improvement. Programs are many times entirely too long and too stereotyped. Let us hear more of the new things! What great pianist is there who plays the works of living composers? They are all afraid of the critics. Even Paderewski doesn’t have the courage to play more than a few of his own compositions.”

I asked Leschetizky for something about modern piano composers.

“I do not consider that the ‘secessionistic’ movement in music means as much for the solo instrument as for the orchestra. One doesn’t find an artist like Ysaye, for instance, putting these ultramodern compositions on his programs. Since the Grieg and the Tschaikowsky B flat minor piano concertos, which appeared at about the same time, there has been nothing so effective written for the instrument in this line.

“Of the Russians, Rachmaninoff has written some interesting things, but has hardly accomplished the great things which his charming C sharp minor Prelude seemed to promise. Of his two concertos I prefer the first. Liadow and Arensky (the latter, alas, only lately dead) composed real piano music, and Scriabine has written some excellent things. Sinding’s compositions are pianistic but not any too original in their ideas. The ‘Frühlingsrauschen’ is well made in spite of the fact that it tastes of Wagner.”

For technical purposes Leschetizky uses almost entirely Czerny with his pupils and I found that he had very good reasons to give for preferring these etudes to those of Clementi, Cramer and others.

“I prefer Czerny because he writes in a more fluent, pianistic style than any of the others. One must learn how to walk straight before one attempts gymnastics. Clementi, Cramer and Kullak are always putting obstacles in the way in their etudes. All at once there comes a clumsy point in a passage which gives you the same sort of feeling as when you get your walking-stick caught in between your legs.

“In Czerny, however, one has a clear road; there are no complications in the figures. If I were to get up now and walk toward the door you see I would have trouble, for there is a stool in the way. If I were a clown from the circus I would probably jump over it; as I am not I shall have to go around it to get out of the room. In Czerny there is never any stool in the way!”

One gets Leschetizky’s meaning immediately by comparing the first study in the “Gradus ad Parnassum” with number one of the Czerny “Art of Finger Dexterity,” or number twelve of the Cramer studies (Bülow edition), with number seven in the same book of Czerny. The contrasted studies deal with like technical problems.

“Clementi, though I find him dry, is good for endurance and velocity. In Czerny, however, one has plenty of chance for endurance and velocity work, and, besides, there is always opportunity for the study of interpretation. He himself laid particular stress on this in the study of his etudes, requiring them to be played repeatedly in different styles, pianissimo, fortissimo, and, lastly, with ‘nuances.’

“Many passages which occur in more pretentious works are not more beautiful than some of the Czerny studies. In Mendelssohn and Beethoven one finds such passages often. The first figure in the last movement of Mendelssohn’s G minor concerto is pure Czerny.”

Going to the piano, Leschetizky played the figure.

“Now, if I play you the first Czerny etude in book two of the School of Velocity, and add a suitable counterpoint in the left hand, you can hardly tell which is the etude!”

The result was just as he had said.

“Liszt, who wrote in his own etudes the most complicated figures of all for the piano, was a pupil of Czerny and used his master’s studies to the very last for technical purposes.”

(To be continued in “The Etude” for May)