Centers for Music Study in Southern Germany

By J. FRANCIS COOKE

The Empire of Wagner.

What an extraordinary impression a great personality makes upon the geography of the world! To the cultured mind the names Bethlehem, Mecca, Constantinople, Aix-la-Chapelle, Worms, Stratford-on-Avon, Waterloo, Weimar, or Mount Vernon do not mean mere spots upon the crust of our planet, but rather the great theaters of the masterplayers of humanity, Christ, Mohammed, Constantine, Charlemagne, Luther, Shakespeare, Napoleon, Schiller, Goethe, or Washington. The musician translates Bayreuth and Munich into one single word—Wagner. The greater body of music-students flock to Munich and Bayreuth principally to come in closer touch with the great master’s works. They want to feel themselves in the very theater in which he acted the most important part of his great life-drama. They want to see his last resting-place in the garden of “Wahnfried;” standing by the plain, flat stone in the little grove of trees, they realize, for the first time, perhaps, the true extent of the empire of the Master. The empires of Cæsar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon—where are they? The empire of Wagner is the civilized world. Prince and pauper bow alike to his genius.

The Pilgrimage.

Not all of those who go to Bayreuth go as students, but few leave without having learned. Of all pilgrimages, there is none more striking and picturesque at this day than that which is made to this musical shrine. The true pilgrims set such a remarkable example to all others that the spirit proves infectious; in a short time all become confirmed Wagnerites,—if only in their imaginations. Should you go by train from Nuremberg, you will find that even the beautiful Franconian Switzerland and the lovely river Pegnitz have few charms for your fellow-travelers, for they are studying little yellow librettos or great ponderous scores as diligently as a lot of schoolboys on the day before examination.

Bayreuth.

Arriving at Bayreuth, you are at first struck with the plainness of the attire of the majority of the pilgrims. To many it must surely have been an effort to have purchased a single ticket at five dollars for one performance. As you walk through the commonplace, uninteresting streets you cannot but feel a deep regret that such a great movement should of necessity have its center in such an insignificant place. Wagner went to Bayreuth for seclusion, it is true; but how much more delightful would a pilgrimage seem if the Wagner National Theater had been situated in Eisenach, Nuremberg, Salzberg, Munich, Würzburg, or Rothenburg! Wagner, however, like all great men, did what he could, and was able to discern closely between the possible and the impossible. It would be difficult to imagine a more ordinary town than Bayreuth. Many of our American cities possess far more picturesque beauty. Aside from the theater, Wagner’s home “Wahnfried,” Jean Paul’s house, and the graves of Wagner and Liszt, there are two palaces of mediocre interest and a few feeble attempts at beautification. There are some few industrial enterprises in this city of 30,000 inhabitants, but the principal support of the residents in recent years has been derived from the entertainment (?) of guests. A fine room in a modern hotel in Nuremberg or Munich with electric lights, etc., can be secured by the economical tourist for seventy-five cents or a dollar, while a room in a garret of a dilapidated century-old private house in Bayreuth costs at least $2.00. The hotels are old fashioned and the service generally poor, while exorbitant rates prevail everywhere.

Parsifal.

Parsifal.

“Parsifal” still remains the great attraction at Bayreuth, and is likely to remain so, even though it may be presented in other countries. Moreover it is still a revelation to the one who sees it for the first time. Once the glorious “Abendmahl” motive is heard rising from the “mystic abyss,” floating to the very depths of one’s soul, all inconveniences are forgotten and the dream of the pilgrim is realized. The agony of Amfortas, the faithfulness of Gurnemanz, the fatalistic love of Kundry, the divine heroism of Parsifal, the wonderful transformation scene to the “Grail Temple,” the glorious, solemn tone of the bells, the ethereal sweetness of the boy choirs, Klingsor’s magic castle, the marvelous flower-scene, and the sublime tableau just before the final curtain closes upon the beautiful dream produce a sensation upon the musician’s mind that he cannot describe in words. One cannot but deplore the fact that the whole world has thus far been obliged either to forego this great artistic joy or make a lengthy and expensive pilgrimage to an insignificant German town never intended to accommodate one-tenth of the number of persons that attend the festivals.

Educational Opportunities.

The American student’s question is: What can I learn at Bayreuth that I cannot learn as well elsewhere? This may be very properly answered by affirming that he will receive more instruction at Bayreuth than amusement. The layman will in all probability enjoy the performances at Munich, Vienna, Paris, and Wiesbaden much more, as they are given with a much greater artistic latitude.

Even confirmed Wagnerites must admit that there is much that is stilted in the performances, owing to the enforcement of the letter rather than the spirit of the directions of the master. This makes the work doubly instructive to the student, but less enjoyable to the average listener. In fact, it is the opinion of the present writer that, after the singer has once become familiar with the Wagnerian rôles, and is thoroughly grounded in the principles and practice of correct voice-production, the best school for the Wagner music-drama is in the auditorium of the Bayreuth Theater. The school at Bayreuth is really not a school at all, as compared with the music-schools of Berlin, Vienna, and Paris. Its headquarters are in the home of Herr Prof. Julius Kniese, the vocal director at Bayreuth, and the instruction is largely private. Kniese’s years of experience have given him a hoard of Wagner tradition that cannot but be very valuable to all who study under him. The plan of private study is in line with the best thoughts of Wagner. To one who is generally familiar with the music-drama the performances simply confirm the best that he has seen or read. There has been so little change in the past years that the excellent work of W. S. B. Mathews, “How to Understand Music,” which has brought Bayreuth so much closer to American musicians, is still a standard work, though published several years ago.

The Munich-Bayreuth “Wagner Krieg.”

The present extraordinary contest between Bayreuth and Munich in the Festival Theater matter is being waged with much heat and much unnecessary and undignified criticism upon both sides. A description of the contest throws light upon a matter of current musical history pertaining to the production of Wagnerian music-dramas, that will undoubtedly take a great importance in the annals of the music and drama of the future. In 1817 a German architect, Schinkel, conceived the splendid idea of building a theater with a sunken or concealed orchestra, thus removing from view the technical factors of the instrumental music at operatic performances. It may thus be seen that the “mystic abyss,” as Wagner called the chasm between the audience and the stage and to which he attributed a mysterious hypnotic charm, was not original with him. However, Schinkel’s idea never gained any prominence until Wagner so interested Ludwig II, of Bavaria, in his work that the eccentric monarch, in 1866, ordered the architect Sempner to make the plans of a great National Theater to be built in Munich, which became known as Sempner’s 10,000,000-mark theater. The plans for this theater, however, were not immediately carried out.

Wagner’s Financial Ability.

Wagner’s Financial Ability.

Wagner built his Festival Theater at Bayreuth in 1872. Those who have read the excellent biographical and descriptive works of Finck, Chamberlain, Mathews, and others have a faint idea of the awful financial strain to which Wagner was subjected at that time. That the Bayreuth Theater was built at all was a marvelous indication of Wagner’s financial ability, and of his extraordinary confidence in the principles which he knew to be right, a phase of his character too often omitted from the biographer’s catalogues of the marvelous man’s human achievements. Wagner built at Bayreuth not only as his means allowed, but far beyond, involving him in various financial embarrassments that would have completely overwhelmed a less heroic character. It certainly does appear that the wife who aided him so faithfully at this time should have an interest in the present profits of the Bayreuth Theater, whatever may be the continual allusions to the so-called commercial basis upon which she is supposed to conduct the festivals.

The Model and the Monument.

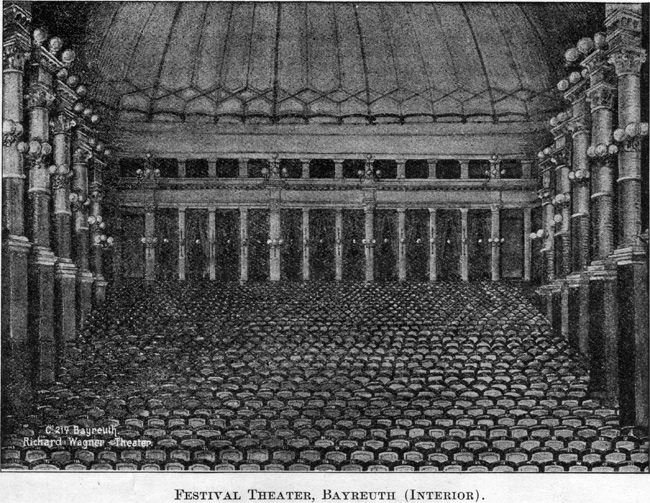

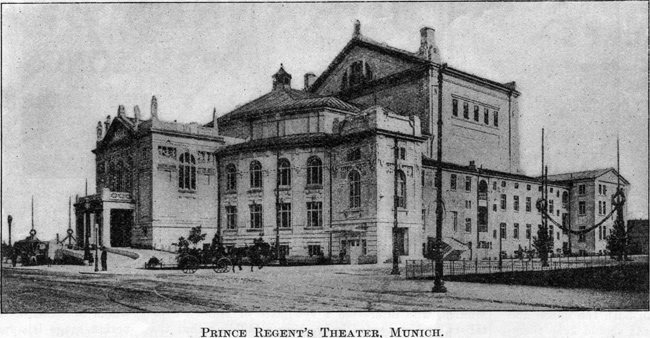

But lavish as Wagner was in his time, his theater fell far below the classic ideal of his own mind and of that of Sempner. He himself expressed a desire in 1872 that a magnificent theater be built to “monumentalize” the house at Bayreuth; in fact, many of the great Wagnerian critics of the day look upon the Bayreuth Theater as little more than the cherished model of the theater of the future. The monument has already been built in the Prince Regent’s Theater, at Munich, opened in 1901. As this particular form of theater will doubtless have a great influence upon both the music and the drama of the future, students should keep themselves well informed in this connection. A better idea of the excellencies and deficiencies of the plan may be secured by contrasting the Bayreuth and the Munich houses. The Bayreuth theater has its greatest claim to interest in being the original of its kind. The features which have made it so celebrated—the sunken orchestra, the side-entrances to the seats, the absence of aisles to provide for the atrocious latecomers, the provision for a perfect view from all of the seats, and the enormity of the stage in comparison with the size of the auditorium have been frequently described by numerous writers. The theater has been so glowingly praised, that the first disappointment of the visitor is usually to find that the house is exceptionally small—as small, indeed, as many opera houses or Y. M. C. A. halls in unimportant American cities. Its seating capacity is 1350. He next finds that the lavish provisions for comfort and even luxury so manifest in the home of Wagner have no part in the Bayreuth Theater. The seats are not only uncomfortable, but are so close together that the audience is obliged to stand until all of its members are in, when they can take their seats with out fear of further disturbance. His next disappointment is to find that the theater, so beautifully designed, is structurally a very unsafe and unsubstantial building of brick and wood. The provisions for exit in case of fire are inadequate, and, should a bad fire ever occur during a performance, the fatalities are pretty certain to be great. The next objectionable feature is the absence of a foyer. All the auditorium exits lead to the open air, and the fate of the auditors in case of a storm may be imagined. The provisions made for meals during the intermissions between the acts of the more lengthy festival plays of Bayreuth are ludicrously out of keeping with the splendor of the performances. Two rough wooden pavilions are erected on either side of the road leading to the entrance of the theater, and the “thirty minutes for refreshments” attitude of the audience, the snatches of sausage and beer, are things so mundane that even the glorious illusion of Walhalla beyond the proscenium is rapidly dispelled in the minds of all possessing a sense of humor.

The Prince Regent’s Theater.

Should a Wagner Festival Theater ever be built in the United States, we should certainly go to Munich, and not Bayreuth, for ideas. The Prince Regent’s Theater is so very fine and so admirably adapted to the production of the operas of all composers, and especially those of Wagner, that it belittles description. The present renaissance of the Wagner movement in Munich is due, not to a renowned musician, but to the famous German tragedian Herr Prof. Ernst “Ritter von Possart, the royal intendant at Munich, who interested a syndicate of Munich capitalists, and succeeded in erecting a building that the enemies of Wagner a quarter of a century before had declared to be an extravagant dream. More than this, von Possart induced the Prince Regent to guarantee the maintenance of the theater for ten years. This done, he put his own brains and experience as an actor into the matter in such a way that the performances are now declared by numerous competent unbiased critics to be even superior to anything ever seen at Bayreuth. The location of the theater in Munich upon the hill known as the Gasteig, in the beautiful suburb Bogenhausen, overlooking the Isar, is possibly not so picturesque as that of the Bayreuth Theater in its frame of arboreal foliage. However, the city of Munich itself is so much more interesting than Bayreuth, from a general standpoint, that one attending a Wagner Festival in Munich, with its great art galleries, its medieval streets, its stately buildings, and the phenomenal palaces of Ludwig II within short distances of the city, cannot but feel much regret that Wagner was not permitted to carry out his original plan of building his National Theater in either Munich or beautiful Würzburg.

The Prince Regent’s Theater itself is so much finer than the Bayreuth theater in many constructional features that the latter is made to appear a very crude or rough working-model of the Wagner National Theater idea. All of the desirable features of the Bayreuth house have been retained, but so many other advantages have been added that any student who visits Munich to see this chaste, classical temple to musical and dramatic art will be repaid. The Grand Opera House in Paris, the new Stadt Theater of Frankfurt, the Hofburg Theater in Vienna, or the Royal Opera House in Wiesbaden, beautiful as they are, with their wealth of ornamentation, must all recede in one’s memory when this simple, substantial, stately building has been seen.

Wonderful Construction of the Munich Theater.

The construction is of stone and iron, assuring a permanency to the building which Bayreuth can never know. The size of the auditorium is the same as that at Bayreuth, but 300 fewer seats have been provided to add to the comfort of the audience. The ample and beautiful foyer is another feature which makes the theater more practical and comfortable than the Bayreuth house. An excellent restaurant built in the theater with a terraced outdoor garden makes it possible for the auditor to secure a meal amid surroundings that do not destroy the illusions of the magnificent performances. The theater is provided with two iron curtains and twenty-six large hydrants for use in case of a possible fire. The stage, designed and patented by the famous Lautenschläger, is nothing short of marvelous. The machinery and other iron constructional or mechanical features weigh no less than 236 tons. The ropework is over 40 miles in length, while the stage is about 140 feet in height, 97 feet in width, and 113 feet in depth. The theater has its own electric plant, and there is also an apparatus for providing rain-effects by discharging at will 66 cubic meters of water. The scenic effects the writer has seen at the Prince Regent’s Theater, especially in the spectacular “Tannhäuser,” looked less like paint and canvas than anything he had previously imagined. With such a frame and such a director as Possart and such artists as he has gathered around him it is not difficult to conceive of the magnificence of the performances. With the permanently engaged Royal Bavarian Court Orchestra, augmented for special occasions to 136, an ensemble of the highest character is assured at Munich that is equal in every way to that at Bayreuth. The chorus at Bayreuth is composed of singers, however, who come from all parts, as the opportunities offered for study in the Bayreuth Chorus are much coveted by many fine soloists, to whom no other means of introduction to the Wagnerian stage is apparent. The chief charms of the performances at Munich lie in the splendid spontaneity of the productions, the magnificent ensemble, the realism of the scenery, the splendid perspectives made possible by the enormous stage, the excellent timing of the singers, orchestra, lightning and general scenic effects, the lack of evident technical friction, and the liberal yet consistent interpretations of Wagner’s ideas in the music and the drama by the great actor and manager, Possart. The difference in the cast of vocal soloists is not pronounced, but Bayreuth probably commands the loyalty of the greater Wagnerian conductors. There is not, however, the same reverential spirit at Munich that is so impressive at Bayreuth. One feels that the occasion is one of an extraordinary series of performances, but not Festival performances attended by pilgrims like those at Bayreuth. The world of fashion has a much greater representation here in Munich than at Bayreuth, and the musician very soon realizes that he is surrounded by many who attend from a standpoint of curiosity, others because it is fashionable, and still others because it is expensive, the price of all seats being $5.00. The number of American and English auditors testifies favorably to our increasing musical interest. The management has even gone so far as to print special announcements in English. Nevertheless there are many attractions at Bayreuth that will draw musicians to the little provincial Bavarian town for years to come. The spirit of the pilgrimage, the memories of the master and his illustrious followers, Liszt, Mottl, Richter, Levi, Seidl, and countless others, the much discussed personalities of his wife and his son, mean more to many musicians than the magnificent theater and the superior performances of Munich.

Parsifal in the United States.

Parsifal in the United States.

The promised performance of “Parsifal” in New York is not likely to interfere with the attendance at Bayreuth nearly so much as has the Prince Regent’s Theater in Munich. Manager Conried’s dramatic experience has been somewhat analogous to that of Possart, and with the importation of the stage designer and director of the Prince Regent’s Theater in Munich, together with Mr. Conried’s enviable reputation earned at the Irving Place Theater in New York and the remarkable cast he has already engaged, Americans should look for an unequaled performance of this magnificent work at the Metropolitan Opera House. But even this most successful manager will be unable to reproduce one thing at Bayreuth that makes the Festivals of such extraordinary interest to musicians, namely, the reverential attention and consummate appreciation of the auditors—an atmosphere peculiar exclusively to the great Wagnerian Mecca.

The Royal Academy of Music.

After the interest which centers about the work of Wagner in Munich the attention of the American student is next turned to the Royal Academy of Music, one of the foremost music-schools of the world, and one of the three government music-schools of Germany. Reorganized in 1867 under the direction of Hans von Bülow, the school has ever since had some musician of international prominence at its head. Cornelius, Rheinberger, Stavenhagen, Baermann, and Wüllner are names of which any music-school might be proud to boast. The school-building is comparatively modern and excellently located, being directly across the street from the Royal Gardens. The building is not nearly so large as those of the Berlin, Leipsic, or Vienna Conservatories, but it readily ranks among the best adapted conservatory buildings in Europe. The city of Munich itself, with the rushing river Isar, flanked with long avenues and narrow lanes leading at times to dreams of medieval Germany, and again to the magnificent Athenic sections, is really a splendid place for this student to spend his years of study. Much more interesting and inspiring is it than Berlin, Leipsic, or Frankfurt could ever be. The charm of environment, together with the undescribable “gemütlilichkeit” or open, jovial hospitality of the Bavarians, has unquestionably had much to do with the direct results achieved by the numerous American musicians who have made Munich their study-center.

Interesting School-Statistics.

Fortunately, the conservatism of Rheinberger and his associates has had much to do with maintaining a well-balanced musical policy in the Royal Academy of Music. Ultra-Wagnerian tendencies and that dangerous radical extremity which any great revolutionary movement makes imminent have been very wisely avoided by the faculty of this remarkable school. During last year there were 40 teachers connected with the institution and 328 pupils, of whom 10 were Americans. The school-term lasts 40 weeks. An interesting insight into the comparative choice of vocations among music-students in Germany may be gained from the following, which indicates the number of students who have chosen the study of special instruments as principal studies in the Royal Academy of Munich: Piano, 106; Violin, 61; Organ, 36; Liturgik (the study of the service forms of the Roman Catholic Church and the music appertaining thereto), 11; Viola, 2; Violoncello, 8; Contrabass, 4; Flute, 7; Oboe, 5; Clarinet, 9; Bassoon, 5; Horn, 10; Trumpet, 8; Trombone, 5; Drum, 3; Harp, 2; Singing, 44; Counterpoint and Composition, 48. This does not include, of course, the instruction of students in the compulsory or semi-compulsory additional studies: Piano (as far as the simpler works of Clementi, Diabelli, Kuhlau, Haydn, Mozart, etc.), Sight-Singing, Harmony, Musical History, and, strangely enough, Dancing and Fencing in their relationship to the stage. Thirteen splendid public concerts were given by the teachers and pupils during last year, including such a work as the “St. Elizabeth” of Franz Liszt. The work at these concerts was all of the highest class, and to the writer’s mind is far more to the credit of the institution than the more numerous mediocre concerts given by some of the private German music-schools, and supposed to represent the activity of the school to inexperienced musicians. The school has a fine library and an excellent student orchestra. The student who goes to Munich and resolves to work earnestly will find assistance at every hand, and, what with the splendid contributions of Art, History, and Nature to this fortunate Bavarian capital, he must be talentless indeed if he returns to America unimproved intellectually, emotionally, and esthetically.