CHRISTIAN SINDING.

I WAS quite young when my first work came into existence, and took it, with trembling heart to a celebrated artiste, asking for a frank opinion upon its value. Several days later,—naturally enough I was willing to allow time for a careful judgment,—after a most friendly reception, the question was suddenly asked me: “Tell me, please, why do you want to compose?”

I WAS quite young when my first work came into existence, and took it, with trembling heart to a celebrated artiste, asking for a frank opinion upon its value. Several days later,—naturally enough I was willing to allow time for a careful judgment,—after a most friendly reception, the question was suddenly asked me: “Tell me, please, why do you want to compose?”

IGNAZ BRÜLL.

ONCE as a boy I went into a park for a walk. It was a beautiful summer day, the birds chirped and sang. And what they sang pleased me so much that I was seized with a longing to imitate them. This effort was my first composition, a piano piece, Vogelgczwitscher (Birdchirpings). Thus the mischief began.

ONCE as a boy I went into a park for a walk. It was a beautiful summer day, the birds chirped and sang. And what they sang pleased me so much that I was seized with a longing to imitate them. This effort was my first composition, a piano piece, Vogelgczwitscher (Birdchirpings). Thus the mischief began.

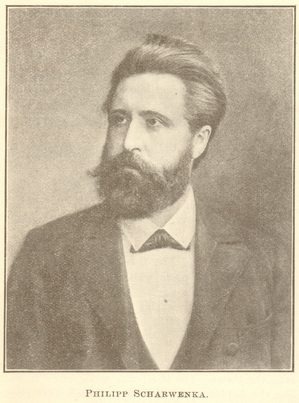

PHILIPP SCHARWENKA.

I AM to tell about my first work, and to do so must go back to the Second Punic War, which, in my recollection, is connected so closely with the composing of my first work.

It was in Posen, at the beginning of the 60’s of the previous century—how very historical that sounds! I had nearly finished my studies in the gymnasium, but I was a scholar only in the morning. Our afternoons were spent in a far different way. The piano-instruction, as was natural in our provincial city, was in the hands of several “Knights of the Stiff Wrist,” and in consequence really served as a guide how not to play. To the best of my knowledge, there was not in Posen, at that time, a teacher who was in position to give instruction in harmony and the other branches of musical science necessary to composition. If we young fellows were almost wholly denied the opportunity to study music seriously and scientifically, so much the more did a “free art” develop among us. No opportunity to hear music was missed, and almost every day in some place there assembled a circle of musically inclined youths, gymnasium pupils, and the younger members of our military band, which gave symphony concerts every week, in which we had our regular place. My brother Xaver, whose uncommon musical talent had already attracted attention in Posen, was always the center of this circle, and was the only one among us who could play well enough to make known to us the hitherto unknown music, as well as to assist in the chamber-music. During the pauses we criticised the music and debated all the points, which at least had the good consequences that we became familiar with much music and gained a look into the structure as well as the arrangement and values of the themes of a musical composition.

It was in Posen, at the beginning of the 60’s of the previous century—how very historical that sounds! I had nearly finished my studies in the gymnasium, but I was a scholar only in the morning. Our afternoons were spent in a far different way. The piano-instruction, as was natural in our provincial city, was in the hands of several “Knights of the Stiff Wrist,” and in consequence really served as a guide how not to play. To the best of my knowledge, there was not in Posen, at that time, a teacher who was in position to give instruction in harmony and the other branches of musical science necessary to composition. If we young fellows were almost wholly denied the opportunity to study music seriously and scientifically, so much the more did a “free art” develop among us. No opportunity to hear music was missed, and almost every day in some place there assembled a circle of musically inclined youths, gymnasium pupils, and the younger members of our military band, which gave symphony concerts every week, in which we had our regular place. My brother Xaver, whose uncommon musical talent had already attracted attention in Posen, was always the center of this circle, and was the only one among us who could play well enough to make known to us the hitherto unknown music, as well as to assist in the chamber-music. During the pauses we criticised the music and debated all the points, which at least had the good consequences that we became familiar with much music and gained a look into the structure as well as the arrangement and values of the themes of a musical composition.In these colloquies my classmate, Below, later a physician, was most prominent. He supported his critical superiority upon the statement, never fully proven, that his piano-teacher understood harmony and had given to him, now and then, a look behind the curtain of this art so mysterious to us. It was he also who first passed from reproduction to production, and surprised me, one day, with the score of a movement of a string quartet. At once I felt it necessary to show him that others could do the same, perchance surpass him. Before this I had felt impelled to make various sketches and outlines which had never been carried out because of my lack of the technic of composition. But now I must go to work.

Day and night the contemplated Opus hammered in my head; I composed at home during my leisure hours, in my classes at school, and principally during the history lesson when the teacher lectured. I had divided my exercise book into two equal parts; the first half I used for motives, outlines of exercises, mathematical problems, and other work pertaining to school-life; the second half was ruled with staves and received my musical inspirations. And while from the platform the Second Punic War was explained and developed in all its phases, I could, simulating a zealous transcribing of the lecture, give myself up to “creative” thoughts and put them down in notes in “Book II.” Several weeks, and the Second Punic War and my work were ended. What I had conceived was nothing more nor less than a symphony in three movements, not for orchestra, but a four-hand arrangement for the piano.

And then came the day when the work was produced at our home, Xaver taking the primo part, I the secondo. It sounded very beautiful to us as a first work. From that time on I was the most celebrated composer in my section in the gymnasium; but my good parents experienced less joy when, after the next examinations, I was promoted on condition that I should pass another examination in history.