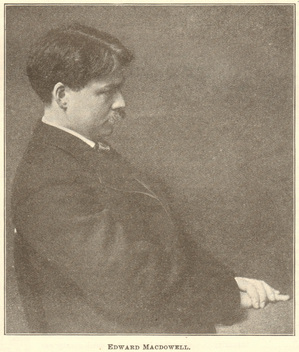

BY strange paradox no man is more generally misunderstood than an honest one. When honesty is combined with idealism, that misunderstanding is apt to be still greater. Judging from personal associations if I were asked to name the two honest among distinguished musicians the names of Theodore Thomas and Edward Alexander Macdowell would occur to me. Differing as they do so widely in personal traits and characteristics, they hold strongly this common one of honesty, a quality that, in the end, no matter what discomforts it may bring into the life of a man, carries him farther and more surely than any other.

Mr. Macdowell, for he prefers this simple mode of address to that of either professor or doctor, to both of which he is entitled, is firm in his opinions, frank in expressing them, impatient of mediocrity, and unflinching in the holding fast of his ideals. In common with most sensitive and intellectual people, he has two distinct sides to his character, that which the world knows and that which shows only to his friends. His dislike of show, push, and parade are strongly developed. Seeing what could be accomplished in the bettering of musical conditions, he would take a way in the developing of them as direct as that of the Czar of Russia, who, when asked to name the route of a railway from St. Petersburg to Moscow, drew a straight line on the map. Naturally, perhaps, for it is human nature, this very directness is a source of offense, particularly with those who have pet theories to propagate; and so many have. His decision once made is final, but, whether agreeing with the point of view of one or another, it is invariably from his own the one of honesty. The chances that have been presented to him are many; those that he has accepted, few. A recent one in this direction is at the moment recalled. The directors of the London Philharmonic requested him to compose a work within a given time for presentation in their concerts. Mr. Macdowell’s reply was that no man could do his best work to order, and within a given time, inspiration, and not opportunity for performance, being the true incentive to write. Again, there is in mind another circumstance, but of which Mr. Macdowell himself has given no word or hint. As it affords an insight to the other side of his character, the gentle one that his friends know, it is well to repeat it. Wishing to be of help to certain people in whom he was interested, and seeing no other way clear to fulfilling his wishes, he composed a set of pianoforte pieces decidedly more in the popular vein than his own style would allow, published them under a nom de plume, and had the royalties sent to his beneficiaries, who were left in ignorance of the source. A gratifying thing to record in this connection is that, even under the conditions existing, with name and style both veiled, the talent embodied in their writing carried them to a large and ready sale.

Mr. Macdowell, for he prefers this simple mode of address to that of either professor or doctor, to both of which he is entitled, is firm in his opinions, frank in expressing them, impatient of mediocrity, and unflinching in the holding fast of his ideals. In common with most sensitive and intellectual people, he has two distinct sides to his character, that which the world knows and that which shows only to his friends. His dislike of show, push, and parade are strongly developed. Seeing what could be accomplished in the bettering of musical conditions, he would take a way in the developing of them as direct as that of the Czar of Russia, who, when asked to name the route of a railway from St. Petersburg to Moscow, drew a straight line on the map. Naturally, perhaps, for it is human nature, this very directness is a source of offense, particularly with those who have pet theories to propagate; and so many have. His decision once made is final, but, whether agreeing with the point of view of one or another, it is invariably from his own the one of honesty. The chances that have been presented to him are many; those that he has accepted, few. A recent one in this direction is at the moment recalled. The directors of the London Philharmonic requested him to compose a work within a given time for presentation in their concerts. Mr. Macdowell’s reply was that no man could do his best work to order, and within a given time, inspiration, and not opportunity for performance, being the true incentive to write. Again, there is in mind another circumstance, but of which Mr. Macdowell himself has given no word or hint. As it affords an insight to the other side of his character, the gentle one that his friends know, it is well to repeat it. Wishing to be of help to certain people in whom he was interested, and seeing no other way clear to fulfilling his wishes, he composed a set of pianoforte pieces decidedly more in the popular vein than his own style would allow, published them under a nom de plume, and had the royalties sent to his beneficiaries, who were left in ignorance of the source. A gratifying thing to record in this connection is that, even under the conditions existing, with name and style both veiled, the talent embodied in their writing carried them to a large and ready sale.With those who know him best Mr. Macdowell is an inveterate joker; the habitual air of shy reserve and reticence gives way to one of genial friendliness. To turn his point he has generally ready some apt story or quaint conceit that recalls the ready, fanciful wit of Oliver Hereford. Of a literary bent of mind, he is a close reader, in large measure along an unbeaten track, particularly in the line of poetry and works of the ideal class. It is not generally known, because his modesty has kept him from acknowledging it, but he has written the majority of the verses which he has set to music. These, and others which he has written from time to time, will before long be printed in a volume for limited circulation. A unique point in this connection is that he confesses that, while the melodies he writes to his songs escape his memory, the words remain always indelibly fixed.

In a talk for THE ETUDE Mr. Macdowell touched upon this point in connection with the theme of song-setting and of poetry as a source of suggestion in instrumental composition. Of the former, Mr. Macdowell said, entering at once upon the subject: “Songwriting should follow declamation. Declaim the poem in sounds. The attention of the hearer should be fixed upon the central point of declamation. The accompaniment should be the simplest point and merely a background to the words. Harmony is a frightful den for the small composer to get into—it leads him into frightful nonsense. Too often the accompaniment of a song becomes a piano fantasie with no resemblance to the melody. Color and harmony under such conditions mislead the composer; he uses it instead of the line which he at the moment is setting and obscures the central point, the words, by richness of tissue and overdressing; and all modern music is laboring under that. He does not seem to pause to think that music was not made merely for pleasure, but to say things.

“Language and music have nothing in common. In one way, that which is melodious in verse becomes doggerel in music, and meter is hardly of value. Sonnets in music become abominable. I have made many experiments for finding the affinity of language and music. The two things are diametrically opposed, unless music is free to distort syllables. A poem may be of only four words, and yet those four words may contain enough suggestion for four pages of music; but to found a song on those four words would be impossible. For this reason the paramount value or the poem is that of its suggestion in the field of instrumental music where a single line may be elaborated upon. In this it elaborates, it extends, and conveys so much of the thought beauty that it embodies. To me, in this respect, the poem holds its highest value of suggestion. The value of poetry is what makes you think. A short poem would take a life-time to express; to do it in as many bars of music is impossible. The words clash with the music, they fail to carry the full suggestion of the poem. If music stuck to the meter in the poem it would often be vulgar music. Verses that rhyme at the end of every phrase make poor settings to music. Many serious poems in meters of that kind fall short of expression in the musical setting. For instance, you can take very serious words and make them absolutely ridiculous. In the setting of words and music the one can absolutely deny and distort the other.

“The main point is to hold closely to the ideal beauty of the song—to sustain the balance of art. English presents great difficulties in the matter of accents, but the French none. English being on a different basis, the accent changes the meaning of the word entirely. In French the syllable may fall on any beat of the measure, but not so the English or German. Many poems contain syllables ending with e or other letters not good to sing. Some exception- ally beautiful poems possess this shortcoming, and, again, words that prove insurmountable obstacles. I have in mind one by Aldrich in which the word ‘nostrils’ occurs in the very first verse, and one cannot do anything with it. Much of the finest poetry—for instance, the wonderful writings of Whitman—proves unsuitable, yet it has been undertaken.

“In the choice of words for song-settings Heine proves the most singable. In the writings of Goethe many poems are eminently singable in every way. Many of the earlier poems by Howells possess these high qualities. The fugitive poems to be found floating in the newspapers often prove excellent material for song-setting.

“A song, if at all dramatic, should have climax, form, and plot, as does a play. Words to me seem so paramount and, as it were, apart in value from the musical setting, that, while I cannot recall the melodies of many of those songs that I have written, the words of them are indelibly impressed upon my mind, and fixed in memory so completely that they are very ready of recall. The poetic significance is invincible, the thought touched me. Music and poetry cannot be accurately stated unless one has written both.

“To have absolutely free rein is to express the poem in instrumental music, where elaboration, extension, and unhampered imagination in development of the subject allow full play to the fancy and the ideal.

“A tendency and an error to which young composers are prone is the undertaking of big things. In the composition class the other day a boy brought me a pianoforte concerto that he had begun, a tremendous, dramatic affair which he was by no means developed sufficiently to possess the materials of expression. Speaking of the situation to him, I could find no apter illustration than the small boy scowling in a corner and who, when asked what ailed him, said: ‘I want to make the whole world tremble at the mention of my name.’ He wanted to knock the whole world down at the first shot. Personally, I have not found the American boy student addicted to rapt and exclusive admiration of any particular composer. He is not a special hero-worshiper. The hardest thing is to make a boy understand the nature of music; he goes in for sound, and not for organic development.

“The homeliest stories prove oftener the surest way of conveying to the young mind an impression—a kind of megaphone method. The humorous side of things and the sarcasm is not lost upon him.

“From observation, I do not think the human animal takes to music. The child likes squeaky sounds; the small boy finds most joy in that fearful noise made by bits of tin and string. It appears natural to prefer ugly sounds rather than right ones. Tschaikowsky has made another element felt in music, an element that has nothing to do with beauty of sound, and yet mighty and potent. Sounds affect us by their texture, as in the instance of the music of Richard Strauss: tremendous, rolling, and majestic.”

As to hours and choice of time for composition, matters which must rest as individual ones with the composer, Mr. Macdowell is erratic. Until he took up his home in New York opposite Central Park, that spreads a map of landscape under his windows, it was impossible for him to write in the city. This glimpse of Nature, even though so limited a one, seemed to supply the missing touch. As it is, however, his principal composing is done in the care-free summer-time, away from town and the claims of work at Columbia University. His country-home is a rambling, old-fashioned place in a quiet corner of New Hampshire. About the house is an old garden that has been a source of inspiration in his work. Beyond this the place comprises seventy acres, mostly in forest. His composition is done in a log cabin, built in the Swiss chalet style, with steep roof. The building stands under a clump of hemlock-trees half a mile from the main house. Some days are spent in complete idleness in the sunny fields or under the shadow of pine-woods; on others, when the working fever is strong on him, he writes from early morning until far into the night and, after a brief sleep, is at it again while the dew is still fresh on the garden.

WILLIAM ARMSTRONG.