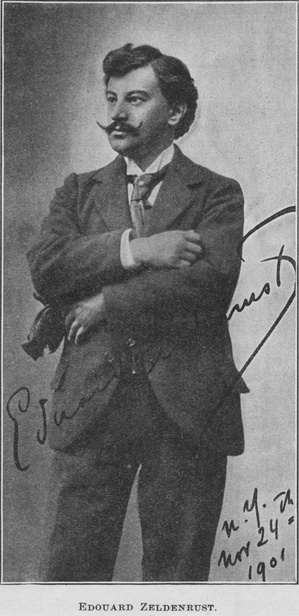

“This morning,” said Zeldenrust, “some one told me that I look like d’Albert; at noon some one else told me that I look like Joseffy; this evening you tell me that I look like Rosenthal. Now, whom do I resemble?”

“This morning,” said Zeldenrust, “some one told me that I look like d’Albert; at noon some one else told me that I look like Joseffy; this evening you tell me that I look like Rosenthal. Now, whom do I resemble?”

“Yourself most of all,” was the answer, “and after that the other three,” which is perfectly true. The pianist has his own individuality strongly marked; he is less self-assertive than Rosenthal, more genial than d’Albert, a good many years younger than Joseffy, and in personal appearance he resembles all three.

A native of Amsterdam, his father, to give him a broader view of art, sent him to Cologne in his early boyhood, where he entered as one of the youngest, perhaps the youngest, of the pupils at the conservatory. After a time his talent was recognized to the extent that he was given a free scholarship, which, to quote Zeldenrust, “was all the more convenient, as my father had then begun to lose the money that he had made. He looked forward with eagerness to my success, and I wanted to realize his hopes. Just as I was on the point of that realization my father died. It was to me a terrible shock, and a profound regret that I could not show him the fruits of what he had done for me. On that account I have always felt more fully my duty to myself in my art.”

A Hollander, Zeldenrust has many of the national characteristics strongly accentuated, but the keynote of his development is an acute observation. He has lived and studied music, outside his native country, in Germany and France; has lived four years in England, and also in Italy. In each he has grown to know the people, and has analyzed national traits and characteristics. He takes things earnestly and thoughtfully. He has reached some sage conclusions. When the question was put to him late in our conversation—“Is your development due to continued study or to observation?”—his answer was: “I have read a good deal, but it has been more observation and experience.”

He has seen much; his associations have been varied. Through his knowledge of men and things, aided by acute powers of observation, he has broadened his mind and developed his ideas. In the case of Zeldenrust we have then to deal with the observer, the man of practical experience. And this is what he says to students on the subjects of: mechanism in piano-playing—the cultivation of muscular development, the forming of taste and aiding of powers of expression, ensemble study, the comparative merits of the French and German schools of piano-playing, and the value of newspaper notices.

MECHANISM IN PIANO-PLAYING.

“Mechanism is only a means to the end,—a very trite thing to say,—but mechanism is a something of which the pianist is always reminded, no matter how great he may be. The very fact that one finger is weaker than another makes one consider it, and there, too, is the old verity that nothing is more difficult than to put the thumb under the finger. Mechanism is a necessary evil; you cannot do away either with the idea or thought of it in playing.

“But persons go too far in the pursuit of mechanism in playing. The man to be blamed most for this is Liszt. This genius, who did so many beautiful things, indirectly inspired other people to be machines.

SHAPE OF THE HAND.

“In the matter of acquiring technic the shape of the hand is the first consideration.Aman born with a large hand with long fingers,—a piano-hand,—has already much in his favor; for the man less fortunate, and having a hand of moderate size and short fingers, will have to work hours to accomplish a stretch that in the first-named case is a birthright. If I had a hand built to play the piano, a born piano-hand, I should not bother so much about mechanism. But the greatest difference, after all, in hands, large or small, is the degree of energy and determination of the possessor. A man with a hand as large as that of Liszt, one that could stretch from C to G,—twelve notes,—has a great advantage. But take, for instance, the hands of many other great pianists, whom it is needless to name for the fact that they are familiar to you, and the possessors of a well-nigh faultless mechanism, and what do you find? That they have hands comparatively small. And how have they gained that finished mechanism? By work directed by constant thought and by intelligence. If a thing cannot be done in one way, it must be done in another. Very well; study out the way your hand can do it best. The very necessity of having to study out the ‘how’ to do things makes every subsequent effort easier.

“Of necessity, and by a fortunate provision as well, early youth is the time of intense application to the study of mechanism—fortunate because of the fact that in youth, before the mind is developed, such study is less irksome.

ACQUISITION OF MECHANISM.

“But later, in the case of the developed artist, it stunts the mind to give so much time to mechanism. I well recall a conversation that I had with Carl Heyman, a man whose success was unrivaled, and who was regarded as one of the greatest of pianists, not only in my own opinion, but that of other virtuosi. For twenty years his brilliant career has been cut short, and he has been an inmate of an insane-asylum in Holland. Then in the fulness of his powers, I went to ask his advice in Cologne. In answer to the question about practice to get mechanism, he said:

“‘All that the artist has to practice every day in this direction is a few scales: play scales for an hour; that is all that is required. But he should not do any more mechanical work than that.’

“How many of those men who devote hours and hours a day to mechanism can be accounted for when the hour for artistic demonstration arrives! They disappear. Without heart people come to nothing. Life has a good deal to do with it; education makes the artist to a great extent. The struggles of life, as well, help make the artist and form his character. You have to struggle and to suffer in order to develop.

“As to education, I have read a good deal, but it has been more observation and experience. I have lived in different countries and studied the people, and that is the best education, after all.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MUSCULAR SYSTEM.

“The frequent tendency of pianists is to place too great stress on the muscular development of the arms. Every morning I use a Sandow apparatus; in a way it is good, but it has a tendency to stiffen the fingers, although it is splendid for the arms. I do not think it at all necessary for pianists to have such developed biceps, but I do think it is necessary, and far more important, to develop the triceps and principally the under-portion of the lower arm. I invented some special exercises on this apparatus for the arm and wrist; but, as I am not going to devote my whole life to mechanism, I gave them up. All the muscle will not do what nervous force will, and that comes from the mind. Muscle may be a help, and I dare say it is; but it will never equal the force of the mind that gives impulse in playing.

“Artists go too far in developing all their muscles. Liszt had no muscles at all, so to speak. So far as I know, Rubinstein never exercised his muscles except on the piano, nor have I heard that Tausig ever practiced with dumb-bells or exerciser. Of course, in one way I fully approve of the use of the exerciser where health is concerned, but not to overdo it for the sake of the piano.

GERMAN AND FRENCH SCHOOLS OF PLAYING.

“Now to the points of contrast and comparison between the German and the French schools of piano-playing. In my residence in different countries I have found the French the most sympathetic among continental nations; America I do not yet know. I have been told that the French are superficial; I have good reason to believe them the opposite. After separation I have found them unchanged. What people think while one is away from them after all matters little, for it is difficult to tell what they think even when one is present. In order to judge of the comparative merits of the German and French schools of piano-playing I studied in both, for six years in Germany and for one in Paris, at the conservatory. So far as breadth and musicianship are concerned, the German school is ahead. The French school is noted for an elegance, charm, and neatness that the German does not possess in equal degree.

“There are some people who have no charm and no breadth to develop, and by such no school can be judged; for they might as well study in the Chinese school, so far as any impression upon them is concerned. I have heard many German players pound the piano; but, notwithstanding that, I think there is more depth in the German after all.

DEVELOPMENT OF TASTE.

“For the development of mind and expression the hearing of good choral and orchestral concerts is absolutely necessary; for the hearing merely of orchestral music is not sufficient; one needs to hear both. Here, again, is another reason why I advise Germany rather than France as a place for study. In Paris, as in New York, you have to pay more for these musical opportunities, and in Paris the distances are great and surroundings antimusical. There is not the same desire to go to hear music that in Germany is second nature, and a desire that carries one away. The hearing of fine orchestral concerts affords one an idea of the greatness of musical art that solo performances will never give.

“Ensemble playing is one of the pianist’s greatest pleasures, and of utmost importance from the musicianly point of view. As soon as the student is capable he should enter upon it. But play with some one who plays better than you.

MUSIC IN HOLLAND.

“I want to point out that the Hollanders are making great strides in music. I can say, I think, without being accused of partiality, that as fine concerts may be heard in The Hague as anywhere in the world. I attribute this completely to the German influence. The Dutch are a little slow and phlegmatic; but, if they take to things slowly, they take to them properly. The Dutch are, however, not as slow as they were. Americanism is getting into us too. People are more restless than they used to be; they are less phlegmatic and less quiet.

MANNERISMS.

“Imitation of the mannerisms in playing of another disgraces an artist. It may be a good thing for financial success, but it is degradation.

“Faddism demoralizes the pianist, as it does the performer upon any instrument.

“Every pianist has a circle of friends that uphold him and make a god of him; but they are very necessary to his courage, his struggle, and his enthusiasm.

PRESS-NOTICES.

“I am skeptical about press-notices. By no means do I despise them; I am glad to get good ones, and equally so to get bad ones if they are deserved. To get a bad notice that one does not deserve is an injustice; but there is, also, no satisfaction in receiving a good notice when one does not deserve it. The greatest gratification to me is the satisfaction of my audience.

“I respect the press,—it is the queen of civilization,—but it is impossible for any critic to ruin one’s career with a scratch of his pen. He may be right, and I think that a sincere critic is always right from his own point of view. An artist may do himself justice at one time and not at another; in such event, and even if the adverse criticism is deserved, it cannot destroy his prospects. If I have played badly one night I strive to make up for it the next. Real, true criticism is not of the kind that knocks a man down in one evening. When asked my own opinion, I give it with reserve; for I know how difficult it is to play the piano, and I know what it requires to do it.”

WILLIAM ARMSTRONG.