BY REV. H. T. HENRY.

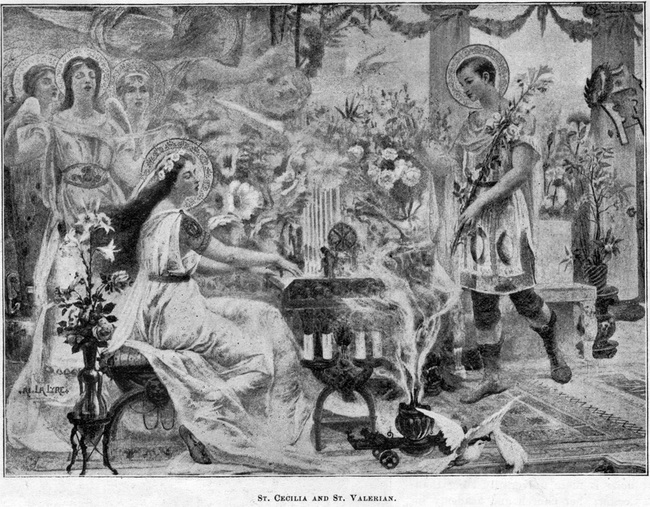

What St. Cecilia represents in music is adequately defined by her symbolism in the kindred arts of painting and poetry. This symbolism is not—like so many others—a fiction founded on fact, but rather a fact founded on fiction. The fact stares us in the face from the pages of Dryden and Pope and from the canvases of Raphael and Delaroche. These poets and painters are but typical of the vast symbolic homage rendered to the saint as the patron of music. But this universal homage is founded on the fiction that the saint was an instrumental musician or, at least, a singer. It is interesting, however, to know that neither poetry nor painting, from the earliest times down even to the fifteenth century, surrounded her with any musical paraphernalia. This omission is not a negative one—the arts dedicated their highest reaches to the celebration of her memory. The martyrologies refer to her simply as “sancta Cæcilia, virgo”; Pope St. Damasus, in the fourth century, composed long epitaphs in hexameters in her honor; for her former abode, which in the fifth century had become a cardinalitial basilica, the Roman church assigned to a special mass certain texts which could easily, and should naturally, have assumed a musical coloring appropriate to her (supposed) patronage of music; the “Acts” of the saint, as we now have them, date back to the fifth century; the sixth century is represented by the series of mosaics in the basilica of St. Apollinaris, at Ravenna, Cecilia being placed among the twenty-five martyrs there commemorated—and so we come down to the thirteenth century, and meet an elaborate fresco of the basilica of the saint at Rome, in which she is painted simply as a richly-clad maiden. In another mosaic in the apse of the same church the saint appears in a cloak and robe of gold, holds in her hands a crown with double circlets of pearls, and stands beside a heavily-fruited palm-tree. No musical symbolism is thought of by the Byzantine mosaist. I have omitted mention of some other paintings of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and shall also pass over quickly to the fifteenth century—a great one for art, and displaying the beginnings of the musical cultus—or, rather, the musical symbolism—which every succeeding age has copied and emphasized so thoroughly as to have associated the saint, in our minds, almost exclusively with her (supposed) patronage of music. But even in that century we find John of Fiesole painting her on a reliquary merely with the palm-branch symbolic of a martyr’s victory. His contemporary, however, Van Eyck, introduces the musical feature, an organ. From that time to our own day, this or some equivalent musical instrument has been esteemed a necessity in any pictorial representation of the virgin-martyr. Thence has arisen a tradition, universally held now by art-amateurs, that St. Cecilia was either an instrumental musician or at least a singer. That she was not cannot, of course, be asserted; but, that she was, cannot be proved. It is very likely, however, that the artistic representations derived their authority from a misunderstood text incorporated in her “office” in the breviary from the “Acts” of her martyrdom. This text runs: Cantantibus organis, Cæcilia virgo in corde suo soli Domino decantabat. . . . The Marquess of Bute’s breviary translates thus: “The musicians played, and the maiden Cecily sang in her heart unto the Lord alone…” St. Cecilia had vowed her celibacy to the Lord; but she is forced to marry. The scene, therefore, pictures the musicians rehearsing the epithalamium, while Cecilia, recalling her vow, attempts to shut out the clamor of earthly instruments and voices, by joining in spirit the celestial choirs and singing in her heart to the Lord, whose grace shall enable her to be mistress forever of her maiden modesty. This text has been misunderstood, as I have just said, because it appears in the breviary without the context of the Acts to explain who the musicians were. The church, however, has continued a long tradition of celebrating her festival with elaborate musical ceremonies, not relying on a misinterpreted text, but on that part of the text which represents Cecilia as joining in the celestial harmonies. The music of earth is forgotten, and that alone of the heavens is heard. Angels and their shawms and psalteries and timbrels perform that higher concert spirituel in which Cecilia joined in corde suo—“in her heart.” And this interpretation it is which has made the saint the patron—not of music in general—but of church-music; that is, the music dedicated to angelic texts and symphonies.

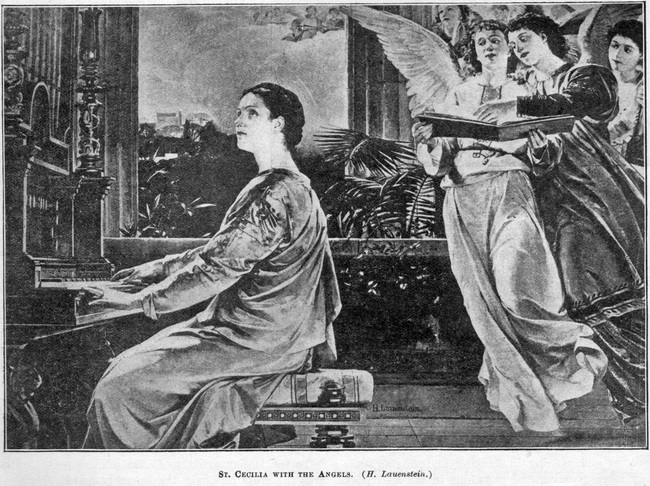

What St. Cecilia represents in music is adequately defined by her symbolism in the kindred arts of painting and poetry. This symbolism is not—like so many others—a fiction founded on fact, but rather a fact founded on fiction. The fact stares us in the face from the pages of Dryden and Pope and from the canvases of Raphael and Delaroche. These poets and painters are but typical of the vast symbolic homage rendered to the saint as the patron of music. But this universal homage is founded on the fiction that the saint was an instrumental musician or, at least, a singer. It is interesting, however, to know that neither poetry nor painting, from the earliest times down even to the fifteenth century, surrounded her with any musical paraphernalia. This omission is not a negative one—the arts dedicated their highest reaches to the celebration of her memory. The martyrologies refer to her simply as “sancta Cæcilia, virgo”; Pope St. Damasus, in the fourth century, composed long epitaphs in hexameters in her honor; for her former abode, which in the fifth century had become a cardinalitial basilica, the Roman church assigned to a special mass certain texts which could easily, and should naturally, have assumed a musical coloring appropriate to her (supposed) patronage of music; the “Acts” of the saint, as we now have them, date back to the fifth century; the sixth century is represented by the series of mosaics in the basilica of St. Apollinaris, at Ravenna, Cecilia being placed among the twenty-five martyrs there commemorated—and so we come down to the thirteenth century, and meet an elaborate fresco of the basilica of the saint at Rome, in which she is painted simply as a richly-clad maiden. In another mosaic in the apse of the same church the saint appears in a cloak and robe of gold, holds in her hands a crown with double circlets of pearls, and stands beside a heavily-fruited palm-tree. No musical symbolism is thought of by the Byzantine mosaist. I have omitted mention of some other paintings of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and shall also pass over quickly to the fifteenth century—a great one for art, and displaying the beginnings of the musical cultus—or, rather, the musical symbolism—which every succeeding age has copied and emphasized so thoroughly as to have associated the saint, in our minds, almost exclusively with her (supposed) patronage of music. But even in that century we find John of Fiesole painting her on a reliquary merely with the palm-branch symbolic of a martyr’s victory. His contemporary, however, Van Eyck, introduces the musical feature, an organ. From that time to our own day, this or some equivalent musical instrument has been esteemed a necessity in any pictorial representation of the virgin-martyr. Thence has arisen a tradition, universally held now by art-amateurs, that St. Cecilia was either an instrumental musician or at least a singer. That she was not cannot, of course, be asserted; but, that she was, cannot be proved. It is very likely, however, that the artistic representations derived their authority from a misunderstood text incorporated in her “office” in the breviary from the “Acts” of her martyrdom. This text runs: Cantantibus organis, Cæcilia virgo in corde suo soli Domino decantabat. . . . The Marquess of Bute’s breviary translates thus: “The musicians played, and the maiden Cecily sang in her heart unto the Lord alone…” St. Cecilia had vowed her celibacy to the Lord; but she is forced to marry. The scene, therefore, pictures the musicians rehearsing the epithalamium, while Cecilia, recalling her vow, attempts to shut out the clamor of earthly instruments and voices, by joining in spirit the celestial choirs and singing in her heart to the Lord, whose grace shall enable her to be mistress forever of her maiden modesty. This text has been misunderstood, as I have just said, because it appears in the breviary without the context of the Acts to explain who the musicians were. The church, however, has continued a long tradition of celebrating her festival with elaborate musical ceremonies, not relying on a misinterpreted text, but on that part of the text which represents Cecilia as joining in the celestial harmonies. The music of earth is forgotten, and that alone of the heavens is heard. Angels and their shawms and psalteries and timbrels perform that higher concert spirituel in which Cecilia joined in corde suo—“in her heart.” And this interpretation it is which has made the saint the patron—not of music in general—but of church-music; that is, the music dedicated to angelic texts and symphonies.  In the masterpieces of the greatest artists she is placed before us as the queen—not so much of terrestrial, as—of celestial harmony. The word “organa” has misled many artists into the supposition that organs, as we know them, were the instruments of the “Acts.” The word, however, means an instrument for any kind of work, musical or other; and, when applied in a musical sense, means any kind of instrument. Dryden, in his two masterly odes, has thus misinterpreted the word and the text as well. In his “Song for St. Cecilia’s Day, 1687,” he institutes a comparison between the modern organ and the other musical instruments:

In the masterpieces of the greatest artists she is placed before us as the queen—not so much of terrestrial, as—of celestial harmony. The word “organa” has misled many artists into the supposition that organs, as we know them, were the instruments of the “Acts.” The word, however, means an instrument for any kind of work, musical or other; and, when applied in a musical sense, means any kind of instrument. Dryden, in his two masterly odes, has thus misinterpreted the word and the text as well. In his “Song for St. Cecilia’s Day, 1687,” he institutes a comparison between the modern organ and the other musical instruments:

“But bright Cecilia raised the wonder higher;

When, to her organ, vocal breath was given.”

In his “Alexander’s Feast” he repeats the mistake:

“At last divine Cecilia came,

Inventress of the vocal frame;

The sweet enthusiast …”

Pope also, in his “Ode on St. Cecilia’s Day, 1708,” associates the organ exclusively with St. Cecilia. Music, he declares, can do wondrous things to earthly passion; but its climax occurs in its power to “antedate the bliss above”:

“This the divine Cecilia found,

And to her Maker’s praise confined the sound.”

In art and poetry, therefore, the special province of the saint is her patronage of sacred music. In the closing verses of their three grand odes, both Dryden and Pope assert the superiority of this music over that of earthly sentiment or passion. Like the musicians of the court of Pharaoh, with their incantations and black arts, Timotheus symbolizes the marvels wrought by earthly melody—marvels great, indeed, but inferior to those wrought by the staff of Aaron when enforced by the grace of the Almighty, and inferior to those similarly wrought by the art of Cecilia, when re-enforced by the same sustaining Power:

“Let old Timotheus yield the prize, Or both divide the crown;

He raised a mortal to the skies, She drew an angel down.”

And in his previous ode Dryden urges the same moral:

“When to her organ vocal breath was given.”

And Pope still repeats the example set by Dryden:

“Of Orpheus now no more let poets tell;

To bright Cecilia greater power is given;

His numbers raised a shade from hell,

Hers lift the soul to heaven.”

This, then, is what “St. Cecilia represents in music”; namely, the superior prerogatives of sacred music. The symbolism is, as I have said, a fact; the tradition on which it is founded is a fiction. The justification of the tradition formed by poets and painters lies in a higher appreciation of the province of sacred music. The attempt should never be out of the hopes of a composer worthily to celebrate the glory and praise of the archetypal harmonist—the fundamental triad of all the harmonies of Nature and grace—the triune God.