BY WARD STEPHENS.

[Some time ago Mr. Stephens promised to write for The Etude about Chaminade, the popular composer. Mr. Stephens had exceptional opportunities of informing himself, as will appear from the sketch which follows.—Ed.]

I first met this now popular composer at an afternoon recital devoted to her compositions, as well as to those of Lalo. It was four years ago, and as I had never seen a photograph of this charming artiste my imagination naturally kept me busy painting all kinds of pictures of her. My knowledge of French at that time being very limited and her English about as good as my French, we carried on a conversation in German, but in a very low voice, I assure you. The French have no love for the Germans or their language.

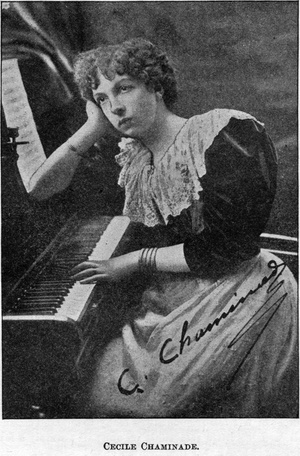

I suppose Chaminade might be called a brunette, although she is not very dark; her eyes are very large, round, and brown, with that absent-minded look in them so peculiar to artists; her hair is of a light brown color, which she wears short and curled; her under-lip is rather large and protruding, and her chin very short. She is of medium height and good build; her hands, however, are very delicate-looking things, and when she plays you wonder where the strength comes from. I have been told that Chaminade is over forty years of age. She does not look it. She is not married; neither is she beautiful; but in conversation her face lights up with animation and a smile which grows very fascinating.

I suppose Chaminade might be called a brunette, although she is not very dark; her eyes are very large, round, and brown, with that absent-minded look in them so peculiar to artists; her hair is of a light brown color, which she wears short and curled; her under-lip is rather large and protruding, and her chin very short. She is of medium height and good build; her hands, however, are very delicate-looking things, and when she plays you wonder where the strength comes from. I have been told that Chaminade is over forty years of age. She does not look it. She is not married; neither is she beautiful; but in conversation her face lights up with animation and a smile which grows very fascinating.

On this occasion Chaminade was the attraction, and her playing, as well as her compositions, compelled the admiration of all present. I was invited to call and see her at her own home, which I did a few days later.

I boarded a train at the “Gare Saint Lazare,” and in thirty minutes I arrived at Le Vesinet, a charming suburb of Paris, and about five minutes from Saint Germaine. It is one of the prettiest and quaintest spots in France.

A walk of about five minutes brought me to the Boulevard du Midi and face to face with a huge iron gate, and on it the number 39. I rang a bell, and in a few moments the gate was opened by a servant, who informed me that Mlle. Chaminade was at home.

In looking through the iron gate I had caught a glimpse of a very pretty garden, and now that I was on the inside I felt shut in from the outside world, like one in hiding. A short walk of a few yards under well-shaded trees brought us to the house, which could not be seen before, owing to the foliage.

I just had time to cast one glance around the place when I was greeted with the genial face and warm handshake of Madame Chaminade, the mother of the composer. Her hospitable greeting put me at my ease at once, and in a very few moments Mlle. Chaminade came into the room. We seated ourselves around a grate-fire for a few minutes’ conversation before dinner-hour, and, strange to say, did not talk music.

We were in the parlor. In one corner of the room were two pianos—an Erard grand and an upright; a few photographs, among them one of Tosti, were also hung in this corner. Chaminade’s compositions, neatly bound, were there in a little bookcase for ready use. Dinner was announced and I was ushered into a square room on the other side of the hall. The house reminded me of some of our old Southern plantation houses, with lots of room and a chance for the fresh air to get in.

The house was completely surrounded with gardens of flowers and vegetables, for Madame Chaminade grew her own vegetables.

At the dinner-table we got to talking about music and musicians, and I found out that Chaminade is no lover of Wagner’s works. She informed me that she had composed when a child, and had some lessons with Godard a little later in life, but that she virtually taught herself. She has composed over four hundred things—songs, piano-solos, duets, orchestral suites, ballet music, organ music—and, in fact, written for every instrument.

She was, at the time of my visit, under contract with Enoch, the publisher, to write so many things every year for a period of three or four years. This handicapped her to a considerable extent, and I could at once understand how it was that some of her compositions should seem to lack inspiration.

For years she has devoted herself to composing and concertizing in France and England, and of late years she has become very popular in England. She is, in fact, a great favorite with Queen Victoria.

Chaminade tells a very amusing story about the Queen’s gift to her. She had played at the Queen’s palace during the Jubilee celebration, and a short time after that the carriage of the English Ambassador at Paris drove up in front of her house at Le Vesinet, and two men in gorgeous livery alighted carrying with them a large parcel. Chaminade was frightened on seeing the men in her house with such an ominous-looking package completely covered with seals, and when she was told that the Queen had sent it she almost fainted. After breaking open the seals and unfolding many layers of paper, she found a photograph of the Queen, with the autograph of Her Majesty.

Chaminade has since then frequently played before the Queen, and when she plays in Queen’s Hall, London, which seats about two thousand people, many are turned away at the door.

In Paris she gives her recitals in a much smaller place, and they are generally preceded by a lecture or an analysis of the compositions on the program, usually by some prominent musical critic. These recitals are intensely interesting; new compositions are introduced in this way, and, again, one has an opportunity of hearing some of the best singers in Paris. I might say right here that Chaminade considers Pol Plantçon the finest artist she has ever heard.

After dinner was over we adjourned to the parlor, and Chaminade brought out a lot of music for two pianos, and for about two hours we had a good time of it, playing duos, solos, and reading songs.

In a few weeks I was agreeably surprised by receiving another cordial invitation to dinner, and I went. This time I was introduced to Chaminade’s sister, who was the wife of Moritz Moszkowski. This time Mlle. Chaminade took me upstairs to her workshop, a very attractive little room on the second floor back, and overlooking the vegetable garden. How quiet the place was!

“Yes,” said Chaminade; “here I can work undisturbed. I never can do any satisfactory work in the noisy city.”

Around the room hung large wreaths, which had been presented to her by various musical societies from all over Europe.

“This was presented to me in Marseilles,” she said, “where I conducted my ballet-music suite. I am very proud of it. I do my best work at night. I can think better and I have more ideas. I love orchestration, and were it not for my concert work I could be found always with my book on orchestration (Berlioz).”

“Do you teach it?” I ventured to ask.

“No,” she replied; “but if you will study it with me it would give me great pleasure to teach it.”

“Do you contemplate going to America?” I asked.

“Yes, some day. I have already been approached by several managers, but Mr. Enoch, who looks after all of my affairs here, has arranged for nothing definite as yet. I should like to see America, and I have received many letters from musical societies and clubs which have honored me by naming them after me, assuring me of a warm welcome when I do visit your country.”

“Do you like England?”

“No. I am always glad to get back to Paris.”

“Do you like the English language?”

“It is not so bad as the German language, and it is painful for me to hear my songs in English. They should only be sung in French.”

Some time after this visit I wrote to Mlle. Chaminade, asking her if I might bring to Le Vesinet a few friends of mine—American musicians—who would like to have the honor of her acquaintance.

Our party was composed of Ethelbert Nevin, Charles Galloway, Ronald Grant, Mr. Rogers (a baritone), and myself. Needless to say, we had a glorious time. Chaminade played, Nevin played and sang, Rogers sang, and I played with Chaminade her “Concertstücke.” Autograph albums were produced and lovely things written in them. Chaminade’s hospitality, modesty, and genius left a deep impression upon all present.

One day I met Fred Schwab, the well-known manager, on the street in Paris. He asked for an introduction to Chaminade, with a view to arranging for an American tour. We all met in Mr. Enoch’s office, and it was eventually understood that Chaminade would make a tour of the United States in 1898, and I was engaged to play the two-piano works with her. The war made Mr. Schwab afraid to go on with the original plan, and it was finally abandoned. She may come next season—perhaps in January—for a short tour.

Chaminade is not a great pianist, like Carreño, Essipoff, Clara Schumann, Bloomfield-Zeissler, or Aus der Ohe, but she plays her own compositions as no else could play them, and when she plays the accompaniments to her songs it is a double treat to hear them. In Paris she is called “Sainte Cecile.”

I have often heard Augusta Holmés’s works compared with those of Chaminade. In truth, they are not to be compared at all; they are very different, and, while the compositions of both are interesting, Chaminade’s are the more so of the two.

I spent one summer in Switzerland—in Lucerne—and while there I wrote to Chaminade, asking her if 500 francs and expenses would bring her to Lucerne to play a concert with me. She replied that she would gladly give her services gratuitously if I would pay her traveling expenses. This shows a big-hearted woman, and as I got to know Mlle. Chaminade better I found her to be one of the loveliest characters I have ever met. She is frank in her manner and thoroughly in earnest with her work. She has no bitter words for anybody. She says that Wagner’s music is not singable, and does not appeal to her. She thinks Massenet a very great man musically, and also in point of technic. Saint-Saëns. also, she has great respect for, and is a warm admirer of Godard. She loves France and the French people ; most of her life has been spent in Le Vesinet.

Moszkowski told me that at one time she gave promise of being a very great pianiste, but that she devoted most of her time to composition.

Chaminade feels that after every performance it will be her last one, owing to extreme nervousness, but still she keeps at it. The French people idolize her, and her songs are the most popular in French salons to-day. In England and in America it would be difficult to pick up a program of a song recital without finding something of Chaminade on it.

But as yet we have not heard her greater things—her orchestral compositions, in which she strongly favors “Delibes.” The portrait accompanying this article was made from a photograph she presented to me in Paris, and is the only one she favors, being much provoked when others are printed.