EDWARD VII and his son the Prince of Wales (later George V) were, according to the Court Calendar, to appear in a military ceremony to take place before St. James” Palace in the heart of London. As an American youth studying abroad, we stood for hours in the “kerbstone” crowd, awaiting the royal party. Finally the portly, bearded king-emperor appeared, wearing the gay scarlet uniform of the guards. He was mounted upon a huge white horse. His tall bearskin hat was at an unintentionally rakish angle. He wore a tired, Oh! so tired expression, which made us realize that his calling was not altogether* a joyous matter.

The band which preceded King Edward, with the solid tread of the British Tommy, likewise wore red tunics. It was composed of “wood winds and brasses.” An old Londoner, seeing the clarinets and flutes, blurted out in disgust, “Thet ahn’t a band. Look at them black sticks they’re tryin’ to play on. My word, there ahn’t no proper band, fit for His Majesty, but a brass band!” Thousands of others in the past thought likewise—a band, to be a real band, should be a brass band, one composed exclusively of horns, trumpets and trombones. In some places there are still brass bands. Now that flutes, clarinets, and other instruments formerly made exclusively of wood, are being constructed of metal, bands of to-day are almost entirely metal.

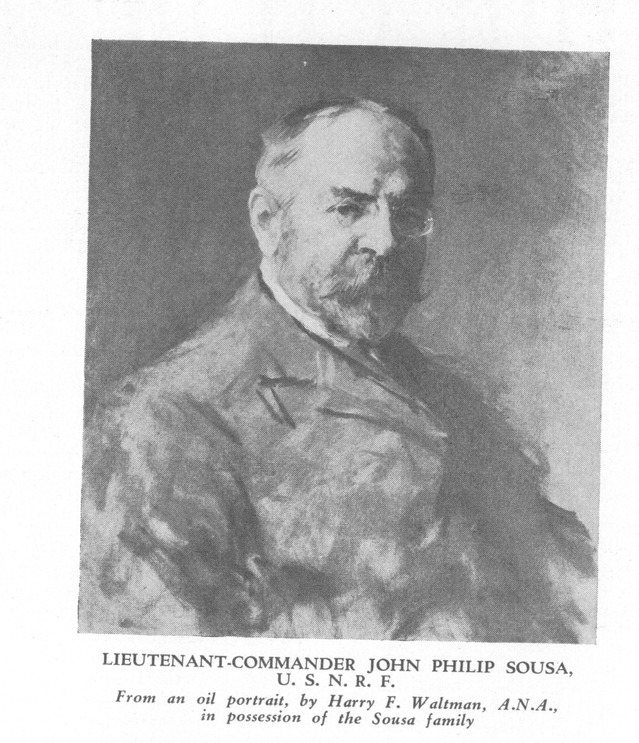

The wide adoption and development of instruments of the wood wind family in the modern concert band is due largely to John Philip Sousa. When Sousa first took his wonderful concert band to Europe, serious musicians were amazed at its flexibility. Here was a hand that could play not only the great band repertoire but also that usually heard through the symphony orchestra, including such an accompaniment as that which it played when the much loved Maud Powell, as soloist for the band, performed the chaste and delicate parts of the Mendelssohn “Concerto for Violin.”

Recognizing to the fullest extent the great industry and effectiveness of the work of Patrick S. Gilmore, who in his day was called “the unsurpassable,” it was, however, not until the arrival of John Philip Sousa that the concert band came into its own. Sousa, although born in 1856, did not begin to exhibit these remarkable possibilities of the band until about 1892, when he resigned as conductor of the United States Marine Band and organized what became one of the greatest of all bands in musical history. His was the first high class American musical organization to tour the world and the first large musical group from this country to command universal interest. This was due to three considerations:

First—To the irresistible personality of Sousa himself, as a human being rich in understanding, humor and sympathy.

Second—To his highly organized musical knowledge and the distinctive character of his instrumentation.

Third—To his very remarkable and original gifts as a composer.

There are many who feel that from the standpoint of originality, dynamic power and highly individual effects, Sousa’s compositions still outrank those of all other American composers, even including our notable symphonic writers. His was an inimitable genius. He was a most patriotic American, a sincere example of the fine Christian gentleman. Born in Washington, D. C., almost under the shadow of the dome of the Capitol, he was trained in the public schools of that city, during and just after the civil war. His father was Antonio Sousa, and his mother, Elisabeth Trinkhaus. The elder Sousa had been born in Spain, of Portuguese ancestry, and had served as a musician in the United States Marine Band. Two honorable discharges from the U. S. Marines indicate that, when he first came to America, he spelled his name Suacca (possibly a Spanish or colloquial spelling of the Portuguese Sousa). His second discharge bears his name properly as Sousa. This evidence, which is at present in The Etude Office files, should put to rout forever the absurd rumor that the name was originally John Philipso (or So, or Siegfried Ochs, or Sam Oaks), to which he has been alleged to have added U.S.A. (S.O.U.S.A.). The name Sousa is a very frequent one in Portugal. Many members of the old Portuguese nobility hear this as a family name.

With the success of the Sousa Band, the type of American concert band was established, and the fine professional hands of Conway, Goldman, Pryor, Herbert Clarke, and Simon were instituted. All of these leaders hailed the genius of Sousa in establishing a type—a type which has served as a model for an unlimited number of hands in schools and universities. Mr. William D. Revelli, in his Band Department in this issue, has been fortunate in securing statements from the directors of many municipal bands. The weekly, Life, in December estimated that there are some one hundred and fifty-six thousand bands in America. If that is the case, we can safely conclude that for the equipment of all kinds, including instruments, music, uniforms, and other items, there must he at least one hundred million dollars invested in American bands.

New influences commenced to invade the hand field before the end of the last century. Just as the waltz influenced the Strausses in Vienna, the dance began to affect music in America. Negro jazz, emanating from the South and spreading to Western honkey-tonks, grew from the ground up and finally began to make an extraordinary impression upon music throughout the world. Irving Berlin (Irving Baline) singing waiter in a slum Chinese restaurant in New York, wrote 64Alexander’s Rag Time Band,” and set continents prancing to it. Europe then imported Negro jazz bands galore. German and French pedants and pundits began to philosophize upon the aesthetics of jazz. The serious old Stuttgart Conservatory actually started a course in Jazz. The leader of one of the famous American Negro bands, that “played Europe” for eight years, was Sam Wooding, a really worth while musician, now conducting the admirable Negro spiritual choir, “Woodland Echoes,” who tells in this issue some of the unusual experiences of his group while abroad as “The Chocolate Kiddies.”

Rhythms, as near to the heart of the jungle as possible, started veritable musical riots everywhere. The whole world seemed bent upon a rhythm “jag.” In California a young man named Whiteman, with a symphony orchestra training, began to recognize jazz as a force, both financial and musical, and set out to capture it. In this issue of The Etude he tells how he did it. His hands are neither orchestras nor bands, but rather a kind of musical hybrid—half band and half orchestra.

After Whiteman came “name bands,” unless you want to date them from the days of Rolfe and Laskey. The hands are named for their conductors, the success of each of whom depends upon his individual and distinctive appeal to the public. The whole dance world started in to emulate this American merry musical warfare, and at this writing there are in New York, London, Chicago, Paris, San Francisco, Rome, Havana, Madrid, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Warsaw, Tokio, Stockholm, Rio de Janeiro, Berlin, Toronto, Dublin, Constantinpole, Nome, Shanghai, Brussels, Athens, and in a thousand other spots, literally armies of men and women rehearsing and performing American jazz. These dance provoking “name bands” are too numerous in America to be mentioned—they include such names as Louis Armstrong, Blue Baron, Cab Calloway, Leo Delys, A1 Donahue, Tommy Dorsey, Eddy Duchin, Benny Goodman, Kay Kyser, Hal Kemp, Wayne King, Ted Lewis, Guy Lombardo, Jimmy Lunceford, Phil Spitalny, Rudy Vallee, Fred Waring, Chick Webb and Paul Whiteman.

The natural law of competition in a lucrative field set them to securing finer and finer musicians and arrangements. The radio sponsors, knowing the interest of the public, paid the hill, until some of the “streamline” name bands presented notably beautiful performances, such as those of Kostelanetz, Vallee and Wilson. They have become the classic organizations of their type. Their directors and players commenced to earn unheard of salaries, clarinet and saxophone performers earning many times as much as most bank presidents.

We do not attribute all this advance to Paul Whiteman, but we do desire to give him credit for sublimating jazz, for directing it to higher levels, and for thus making available new tonal possibilities. This he has done at great personal expense of time, money and effort. His ten “Experiments in Modern American Music” have been really nothing more nor less than ambitious concerts, demanding a much larger group of players and a huge auditorium such as Carnegie Hall. This year Carnegie Hall was sold out for the Whiteman Christmas Concerts at three dollar “tops”; and yet the cost of the “experiment” was such that Mr. Whiteman’s expenses exceeded his receipts by six thousand dollars. His first experiment, in 1924, brought out the George Gershwin-Ferde Grofé Rhapsody in Blue. Victor Herbert (not quite in the idiom) wrote three of his finest numbers for the Whiteman group, for that concert. Subsequent experiments made way for the now famous suites of Ferde Grofé—“The Grand Canyon Suite” and the “Mississippi Suite.” This year’s concert was made notable by brilliant new works from Nathan Van Cleave, Roy Bargy, Morton Gould, Ferde Grofé (a thrilling vision of New York’s World’s Fair called Pylon and Perisphere), and a notable posthumous Cuban Overture by George Gershwin.