By THE RECORDER

Musicians all over the United States are certain to have their curiosity aroused for some time to come over reports of the astonishingly beautiful results of The Clavilux, as the color organ of Thomas Wilfred is known, but since it can only be exhibited in a few of the large cities in the immediate future, it will be a long time before many will have an opportunity to see it.

It is for this reason that The Recorder made it a matter of business to meet the serious, youthful Danish musician and inventor in order to learn as much as words can convey about the main facts of what seem to be an altogether extraordinary instrument, which has already aroused immense enthusiasm and drawn huge crowds wherever it has been shown.

Perhaps the Editor of The Etude may have some question as to whether this instrument falls within the historically preserved musical channels of this paper. Why? Because, in a musical sense, the Clavilux is an organ merely in name. Musically it is as silent as a butterfly. However, the very fact that it has been called an organ is bound to make musical people associate it with music.

More than this, it was invented by a musician, it will unquestionably be shown in public in the future in connection with the performance of musical compositions, and the compositions played by Mr. Wilfred himself upon the organ have a very obvious analogy to music which is of great interest to music-lovers who like to be up on things but who do not want to swallow the garbled reports of enthusiasts.

The Clavilux was exhibited privately and then publicly in New York, once at an auditorium patronized by esoteric groups always glad to revel in anything unusual from pink cats and opaque verse to cubist nightmares and musical epilepsy. The organ was again shown at a large moving picture theatre of a wholly popular appeal (The Rialto). Then it was brought to Philadelphia where it was displayed in the Wanamaker auditorium—“Egyptian Hall,” and later at the Stanley, Philadelphia “Movie” Palace. At all times it drew ever increasing crowds, and at Wanamaker’s hundreds were turned away. This is cited merely to indicate that it has a widespread fascination—a human appeal. In Philadelphia the possibility of its use with a presentation of the Scriabine color-poem Prometheus, with the Philadelphia Orchestra is discussed.

The Clavilux was exhibited privately and then publicly in New York, once at an auditorium patronized by esoteric groups always glad to revel in anything unusual from pink cats and opaque verse to cubist nightmares and musical epilepsy. The organ was again shown at a large moving picture theatre of a wholly popular appeal (The Rialto). Then it was brought to Philadelphia where it was displayed in the Wanamaker auditorium—“Egyptian Hall,” and later at the Stanley, Philadelphia “Movie” Palace. At all times it drew ever increasing crowds, and at Wanamaker’s hundreds were turned away. This is cited merely to indicate that it has a widespread fascination—a human appeal. In Philadelphia the possibility of its use with a presentation of the Scriabine color-poem Prometheus, with the Philadelphia Orchestra is discussed.Before attempting to put into words a description of the instrument and its effects let us review the work of the man and note some other work in a similar field.

The idea of combining color with music is as old as the stage itself. In modern times Mary Halleck Greenwald, an American pianist, has worked at this problem with similar aims, and in London, in 1913, Wallace Remington, an English portrait painter, exhibited a form of color organ and, according to Mr. Wilfred, developed a very interesting notation for color-organ compositions. Right here we see a close analogy to music, for color-organ compositions must have a score.

Thomas Wilfred, the inventor of the Clavilux, was born at Nåsted, Denmark, in 1889. His earliest professional work was that of a journalist, but in his youth he had studied piano and later, discovering the possession of a fine voice, he decided to make a speciality of singing folk songs. He then studied voice with Monceau in Paris, San Carolo in London, and Valdimir Talvi in Copenhagen, thereafter making many tours in Europe and in America as a singer. He also studied the old twelve-stringed lute in order to accompany himself. There are very few performers upon this instrument.

During much of this time he was dreaming of the possibilities of the color-organ. His present instrument, he intimated to The Recorder, was the result of some seventeen years of experiment.

Wilfred has all the serious mien of his race, the alertness of the blond Norseman, and his blue eyes have the sincerity and candor of the real artist forgetting himself in the quest of an ideal.

In discussing his invention he makes clear that he realizes that it is as yet only in its infancy and he hesitates to attempt to complete his system of notation until his instruments become more fixed in type, as far as the manuals and pedals are concerned. However, despite large financial offers, he is in no hurry and sees the wisdom of keeping the development of the instrument floating for some time to come.

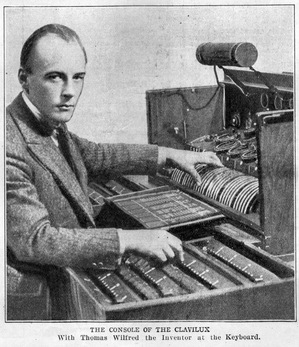

The instrument used in his public exhibitions is valued at $12,000. The average person in viewing it would see first of all a large steel box about six feet wide, five feet tall and twelve feet long. At one end of this is the console or keyboard, but in no way resembling the organ manuals. The keyboard employed by Remington, in London, resembled that of the piano somewhat, but the Wilfred keyboard is totally different. On the right and on the left in front are four grooves with knobs which serve to increase or diminish the amount of electricity employed. In front are a series of discs about the size of phonograph discs set on edge, facing the player and capable of being revolved. On the edges of these discs are numbers of from one to one hundred each indicating the amount of color intensity desired. That is, a blue may be used which can be given a crescendo from the palest tint of dawn to the deepest blue of midnight. Behind the discs are a series of circular devices like saucers lying on a table which when revolved give the mysterious forms which will hereafter be described.

The front of the steel box has a long door which when opened makes the aperture through which the colors are projected upon a screen similar to that used in moving pictures.

Up to this time the Recorder is morally certain that the reader has an idea that the colors projected upon the screen are merely a giant form of kaleidoscope. At least that is what the Recorder himself expected to see.

Can we paint verbally just what is really seen? Imagine the depths of the very heavens themselves, at midnight in the infinity of space. Place in this, moving forms altogether lacking in any of the angularity of the kaleidoscope but more like exquisitely colored smoke, dream clouds, silken veils, fairy cathedrals, birds, flowers, the arctic aurora borealis, fleeting souls, never definite, never fixed, always moving, always changing, coming and vanishing with an array of color so exquisitely beautiful that artist and layman sit in silent delight. The first astonishment, however, is the fact that the colors are given movement, form and texture. Unlike the moving picture which is flat upon the screen, the Clavilux seems to destroy this idea of flatness and everything has density and surface. The veil-like films for instance, are transparent on the screen and one can see other veils behind them.

The only sound was occasional gasps of admiration. Silent music!

The musician soon discovers that for the first time in his life he is seeing a composition. In the first composition, played by Mr. Wilfred, ghostly draperies of silk floated in from each side of the screen while from the center arose in different forms, shapes and grotesque designs of light, which floated to the top and faded in the distance. Soon one realized that a certain very slow rhythm was being preserved and that the different forms and colors were being used in a manner very similar to that in which a composer creates a symphony or a sonata or any other balanced composition by means of contrasted recurring themes.

A composition written for the color organ can thus be repeated exactly at each performance or it can be modified to suit the whim of the interpreter.

Mr. Wilfred produced his results by means of color filters, prisms, and in various other ways not yet revealed. He is anxious to devote all his time to laboratory work, giving up his concert tours and training others to play his instruments as soon as he can feel that they are a little better standardized. He has a feeling that musicians will play the instrument but that artists will become better color organists at first because of their superior knowledge of color harmony and composition.

The Recorder does not agree with him in this, because a great deal of the beauty of the work which Mr. Wilfred has shown is due to the very slow but very regular rhythm he preserves in introducing the color and form motifs and reiterating them. In this the trained senses of the musician will be found important.

In the exhibition given in Philadelphia, the Clavilux compositions played by Mr. Wilfred were made part of programs composed of music and dancing, but while the color organ was used the house was in absolute silence.

In previous presentations of musical compositions with some color plan as the performance of the Prometheus Tone Poem of Scriabine with the Russian Symphony Orchestra of New York, at Carnegie Hall, where a small screen was used, the object has been in most cases, to show a continuous color. In fact the Scriabine score, in which he has paralleled the musical score with a staff to indicate color, merely indicates a change of solid color. Of course this is wholly different from the Wilfred instrument, in which mobile ever-changing forms are introduced with continually changing colors. If Scriabine had grasped the possibility of the invention of such an instrument he would have written a different score.

In previous presentations of musical compositions with some color plan as the performance of the Prometheus Tone Poem of Scriabine with the Russian Symphony Orchestra of New York, at Carnegie Hall, where a small screen was used, the object has been in most cases, to show a continuous color. In fact the Scriabine score, in which he has paralleled the musical score with a staff to indicate color, merely indicates a change of solid color. Of course this is wholly different from the Wilfred instrument, in which mobile ever-changing forms are introduced with continually changing colors. If Scriabine had grasped the possibility of the invention of such an instrument he would have written a different score.The necessity for an adequate notation is one of the great problems of the color organ,—in some of the notations devised at present the staves, if they may be called that, run perpendicularly on the page instead of horizontally as in music.

Mr. Wilfred makes clear that he does not feel that there is any physical connection between the ratio of musical vibrations and color vibrations. Music is represented in hundreds and thousands and color in millions and billions. Sound, he insists, is limited to the planet while light is trans-terrestrial, going indefinitely through space. A cataclysm caused by the collision of two heavenly bodies might occur sixty years before the light messages could reach the earth to tell us about it. He therefore insists that the art of the eye is a higher art than that of the ear,—a discrimination which the Recorder is inclined to feel is trivial. Whether sight is or is not the more important sense cannot be determined by argument. The blind man could possibly decide that it was.

Have the color organ compositions, as yet in their infancy, any meaning? No more than has a Brahms’ symphony. They are merely an expression of the beautiful addressed to the eye rather than the ear. They have no more value than fine music and they are no more important than a lily, a rose or an orchid. But who would want to live in a world without beautiful things. When the color organ is seen with a great orchestra it will be necessary to have the orchestra and the conductor hidden completely. The composition must be played in a room entirely without light except that which proceeds from the organ itself. Of course they are visible with some lights lit but they are seen to best advantage in a room made as dark as possible. The inventor insists, however, the greatest delight will come from seeing the organ without association with music,—a queer statement coming from a musician. Notwithstanding this, the public will demand to see this instrument not only with music but with modern expressionistic stage scenery as well. There is little doubt that some of Mr. Wilfred’s light and color discoveries will be employed in the theatre to wonderful advantage.

One of the principal applications of the organ, according to Mr. Wilfred, will be in connection with therapeutics. He claims that the importance of color in treating nervous and some other disorders has been well recognized by reputable specialists. Just how the color organ may be applied he does not know, but he is certain that it will have usefulness in such cases. The best colors for the nerves, he feels, are combinations of red and yellow, also warm greens verging toward the yellow.

It is not unlikely that the inventor is right since the tremendous value of various forms of light has already been recognized by great physicians,—among them the celebrated Dane, Dr. Finsen, whose employment of the Finsen lights to cure lupus,—a chronic tuberculosis disease which eats into the skin, is now widely acclaimed.

The mechanism of the Clavilux, and certain parts, is extremely delicate, so that it cannot be transported by railroad but is taken from place to place in an upholstered, slow moving van. The organ develops severe heat because of the amount of light used but this is overcome by batteries of electric fans used for cooling.

To describe the Clavilux is like describing music. The reader may have gained some idea from this, but the actual seeing a performance may give him a very different idea. Because of the fact that the inventor insists upon developing his work and his art slowly, it may be years before some of the readers of this article will see the organ. The expense of manufacture, the fact that practically all of the instruments thus far made have been made by hand, and the difficulties surrounding performance, unfortunately make it a little distant from the average man and woman. It is hardly conceivable to the Recorder that this instrument will ever assume a form that would make it practical for home use as is the talking machine and the radio. For the years to come the performers will probably be limited in number and the organ will be seen chiefly with orchestras or in moving picture theatres.

When Schumann first discovered Chopin he coined the famous phrase “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius.” When one reviews the accomplishments and the serious ideals of Thomas Wilfred, such a remarkable future for his invention is seen that one can think of no better expression, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius.”