By THE RECORDER

That Schumann-Heink is a born mother is a fairly well established fact.

It is a question whether she would rather sing or rather extend that wonderful motherly care to some one hungry for her parental affection.

Many a time she has poured out her sympathy and protection to some young person who has wanted just that thing more than anything else.

Once the Recorder saw her with a young actress, now famous, but at that moment discouraged because her play refused to galvanize the box office. It was beautiful to see her smile new encouragement into that young soul.

The great singer has had so many boys in her own family that she knows that the boy’s heart is very close to his “tummy” and once when calling upon her with his own son he was not surprised to see the tragic Ortrud walk into the room smiling behind a cantaloupe filled with ice cream, saying:

“I heard that the little boy was here.”

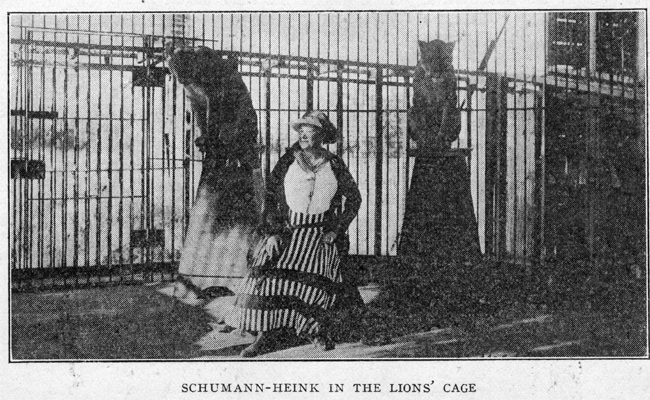

Fancy this combined with an intrepidity that is a surprise to all who know her.

A few years ago she sent the Recorder a picture of herself taken in a cage full of lions connected with a moving picture studio at Los Angeles.

When the Recorder asked if she was not afraid, she raised her plentiful shoulders and said,

“Warum? I didn’t hurt them and they didn’t hurt me.”

Houston, Texas, recently had a very successful season of opera under the direction of De Feo.

Houston, Texas, recently had a very successful season of opera under the direction of De Feo.One of the tenors was Zerola, who was scheduled to sing Verdi’s Otello to the Desdemona of Zelina de Maclot.

The management noticed that there was a great demand for admission upon the part of the colored population and did not dream of the reason until they realized that Zerola’s picture had been shown as the moor and it was believed by many that he was a negro.

In that part of the country it is the custom to confine the audiences at performances to citizens of one color.

While the educated residents of the city in great number appreciated the beauty of Shakespeare’s moor translated into opera by Verdi, the management is said to have received bitter letters condemning the performance, because it represented the swarthy Otello as the suitor of the fair Desdemona.

Everyone who knew Teresa Careno was fascinated by the simplicity and charm of the woman.

Although she was born in Venezuela, she had lived in America so long that she gave one the impression that she came from our own wholsome middle West. Indeed, she was so like a dear aunt of the Recorder that he used to call her “Aunt Emma,” greatly to the amusement of the famous pianist. Her English gave not the slightest suggestion that she was other than an American. What a wonderful teacher she must have been years ago at the time when MacDowell was a youth. She has often described to the Recorder the delight she took in teaching the famous American master. MacDowell liked Careno because she was vivacious and human, and she liked him because he was a real boy. Once in a burst of confidence she cold the Recorder that she knew that the American people were aghast at her four matrimonial ventures, but when she outined (sic) some of the reasons she had for discarding some of her husbands, the wonder was how she endured the situation as long as she did. Fortunately, before her passing, she spent many happy years with her faithful and devoted husband, Signor Tagliapietra, who was the younger brother of her gifted but fiery second husband, the baritone Giovanni Tagliapietra.

Beyreuth is waking up again after its slumber during the war. Meanwhile Frau Cosima has followed Richard to Valhalla and the work is to be taken up by other members of the Wagner family—probably led by Siegfried. But Cosima was a large part of the show at Beyreuth. Just as P. T. Barnum, long after he had disposed of a large part of his interest in “the world’s greatest educational exposition of wild beasts, freaks and feats of aerial agility,” used to be driven around the three rings of his circus in a victoria, Cosima made her state appearances in carriage from Wahnfried to the Festspielhaus and was regarded with awe, not merely as a matrimonial relic of the great Richard or as the daughter of Liszt and the countess d’Agoult, but as a very remarkable woman indeed, whose managerial ability was second only to that of her amazing husbands. Once when visiting Wahnfried the Recorder was carried away by the spell of the wonderful residence that Wagner had made for himself at this shrine. One of his step-daughters showed the writer the remarkable construction of the house. It is not unlike the plan of the Spanish-American home, a large central court surrounded by rooms. In this case the court was a room and in that room the only furniture was a piano—Wagner’s piano. There were no pictures, no clap trap furniture, nothing to mar the simple dignity of the place. There Cosima held her salons—and what memorable salons they were, with the culture of Europe always eager to attend. What the removal of Cosima may mean for the future of Beyreuth will remain to be seen.

Rupert Hughes seems to be spending most of his time very close to the centers of movie-dom in California these days. What a remarkable exhibition of manifold intelligence he presents! Starting in life as a musician, writing musical dictionaries, then branching off to literature, turning out novel and short story and play and moving picture scenario one after the other in such rapid succession that he is now one of the wealthiest writers in the world; he still has his old hankering for music. Indeed, judging by the conversations that the Recorder has had with him he would rather compose than do anything else. It is hard for his friends to fathom in his quiet, unobtrusive manner how he has managed to accomplish so much. A few years ago he sent the Recorder a copy of a twenty-eight page song on the subject of “Cain.” It was designed for a baritone and was as modernistic in treatment as if it had come from the pen of Erik Satire. Indeed, the harmonic treatment was astonishing. Certainly not more than a score of baritones would attempt to present it in concert, but doubtless many purchased it out of curiosity, just as folks buy Liszt Rhapsodies and Balikierev’s The Lark, to see how difficult they are, although they never have the slightest intention of playing them.

You would like Rupert Hughes if you knew him. He has the same ingratiating charm in his conversation that has made his books such great successes. One of his very best friends is Paderewski, and when Hughes was a Major in the army (yes, his versatility runs into that, too) he and the great pianist were much together in Washington. Probably no writer in America has ever

reached a larger audience unless it be Mark Twain or Harriet Beecher Stowe. His books, stories and plays have been translated into many languages, and his movie-successes, like The Old Nest, have been seen by millions.

Whatever may be said by pessimists there is no doubt that even in New York City prohibition is really “prohibitioning” to an altogether unexpected degree. This must be a source of relief to some managers whose “artists” found it difficult to keep their noses out of the flowing bowl. In recent years musicians seem to have lost the reputation for imbibing too freely. Even when there was nothing to prevent them American music workers were for the most part a very sober lot. Indeed, our European contemporaries often explained that that was what was the matter with American music. The American, on the other hand, has never been able to see, since our great poets and great inventors and great architects have been able to produce wonderful creations, why it should be necessary for the musician to pump his inspiration out of a beer barrel. In the old days, however, John Barleycorn certainly did play some merry pranks upon visiting performers. In one instance the Recorder actually locked a man up in a green room in New York City to prevent him from going on the stage and ruining his career. In another instance, a famous violinist, now a resident of a large Eastern city, was engaged to play in a Baptist church in Brooklyn. Unfortunately, the poor man, who, perhaps, had had a glass of wine too much for supper, mistook the entrance to the Baptismal Font for the entrance to the stage. The font was in a decorative arch immediately behind the pulpit. Loud screams helped the Recorder and some friends to locate him standing waist deep in the water of the baptismal font, holding his Strad over his head, in full view of the audience, and calling down the maledictions of hate in Walloon French. Certainly the language was very different from anything that had hitherto been heard from the pulpit. Some friends procured dry clothes and the concert proceeded with a very much injured, but very sober gentleman as the artist of the evening. He was none the worse for his aquatic experience. Even the minister of the church, who happened to be in the audience, could not help roaring at the poor man’s predicament. Let us hope that the violinist made it a rule not to imbibe when he played engagements in Baptist churches thereafter.

Scores of the ablest American musicians have been total abstainers all their lives. As far as we can see their productions are quite as beautiful and quite as inspired as others who have formed a partnership with Bacchus.

What if your name were Christopher Columbus and you had to be introduced by that cognomen upon every occasion to smiling strangers? How would you like to be William Shakespeare, the “grand old man of English song” and have the task of living up to such a great reputation as such a name implies? Fortunately nature endowed the great singing teacher with musical and social gifts which enabled him to rise to the top of his profession. However, one can only imagine the embarassment (sic) he must have at times in writing his name upon a Hotel register. Once the charming elderly gentleman when calling upon the Recorder gave his name to the telephone operator to ascertain whether The Recorder was in his apartment.

”Will you please tell him,” he said with a smile, “that William Shakespeare, of England, is calling.”

“William Shakespeare?” ejaculated the operator !

“Yes, William Shakespeare,” replied the maestro, impatiently.

“W-w-w-w-w-wu-wu-william Shakespeare ?” she asked again.

“Yes, certainly,” he answered, a little irritated, “or if you choose, you can say John the Baptist, or George Washington.”

The Recorder’s bell rang and a much scared voice whispered, “Better come down at once. There’s a crazy man here who says that he is William Shakespeare, George Washington, or John the Baptist. Please hurry.”