By the Noted Composer of Indian Works and Collector of Indian Themes

By the Noted Composer of Indian Works and Collector of Indian Themes

THURLOW LIEURANCE

(The Cuts Used in this Heading are Portraits of the Famous Indian Singer, Princess Watahwasso)

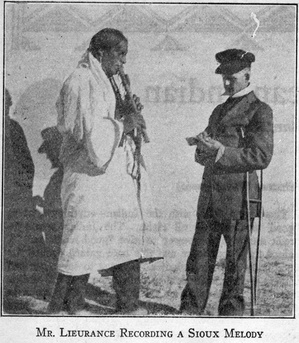

[Editor’s Note.—Thurlow Lieurance was born at Oskaloosa, Ia., March 21, 1880. His father was a physician. His early training was as a cornetist in the town band. He then studied under the finest instrumentalist, Hermann Bernstedt. At the age of 18 he enlisted in the United States Army, became a bandmaster in the 22d Kansas Regiment and served through the Spanish-American war. He saved $400 and went to the Cincinnati Conservatory where he studied composition under Frank Van der Stücken, voice under W. L. Sterling and piano under Ollie Dickenshied, score reading under Bellstedt and Van der Stücken. When all his money was spent he took a position as chorus man in Savage’s Castle Square Opera Company at a salary of $10 a week. During the 2 years he studied 50 different operas, ranging from “Pinafore” to “Tannhäuser” and from his meager salary purchased a complete score of every work he had sung. Standing in the wings he reviewed the opera at every performance. Then he became a teacher in a small Kansas village. He next organised the American Band which played on the Chautauqua circuits for several seasons. In 1895 the United States Government employed Lieurance to make Indian records at the Crow Reservation where his brother was a physician. He made many records which are now kept under seal at the National Museum at Washington. He has made innumerable records which are preserved in many great universities here and abroad. He has visited and made records from a score of different tribes making prolonged stays at different places. Upon one occasion a wagon upon which he was riding, in the Yellowstone, in midwinter, broke down throwing one companion down a ravine half a mile deep and injuring Lieurance so that, together with the consequent freezing in a temperature of over 20 degrees below zero, his legs became crippled for life.

This is one of the great sacrifices that Lieurance has made to preserve Indian music. Mr. Lieurance’s beautiful songs have had an international success and stand as a foremost achievement in American Indian music.]

To know the heart and soul of the American Red Man has been the dream of my life. This wonderful race which, in its branches, had manifested a remarkable phase of civilization long before Columbus ever dreamed of coming to America, has a fascination for the intelligent white man who realizes that in all civilization there is a scale of character from the lowest to the highest.

To know the heart and soul of the American Red Man has been the dream of my life. This wonderful race which, in its branches, had manifested a remarkable phase of civilization long before Columbus ever dreamed of coming to America, has a fascination for the intelligent white man who realizes that in all civilization there is a scale of character from the lowest to the highest.

It has been my fortune to live for long periods among the different tribes of Indians in various parts of the country. Members of my family have married into Indian families; and few musicians have ever had the intimate opportunities that we have had to investigate the music of the American Red Man. I have taken innumerable notation and phonograph records of the melodies played by my Indian friends and have had ever increasing opportunities to see the rich mine of beauty which these melodies contain.

I have said that there are scales of civilization among the American Indian, precisely as among any other races. There are good Indians, bad Indians, intelligent Indians, ignorant Indians, skilled Indians, unskilled Indians just as one might expect the same trace from the Italian, Russian, English or Chinese. Some Indian tribes are very much more musical than others as some are much more artistic than others. Some are unquestionably very savage when aroused, while others are, in some ways, as peaceable as any of the other races of the world.

Of course, there have been many efforts made to show the connection between the Asiatic races and the American Indian. It is, to my mind, a mistake to group the Indian as either Mongolian or Malay. They have been in America such an indisputably long time that they are in every sense of the word “Americans.” If they are not Americans how can we call ourselves Americans? The arts and crafts of the Incas of South America, the Aztecs of Mexico and Yucatan reaching back one or two thousand years, point to a civilization which is still a source of astonishment to the ethnologists and archaeologists.

Early Experiences

My father was a physician, a pioneer doctor. He went out on the plains of Kansas at the time when the buffalo was being driven still farther west. I was born March 21, 1880, but I still remember the wagon-trains moving along the Arkansas river laden with buffalo meat and hides. They passed our little sod house in long persistent lines. As a child I helped tan and care for the hides in order to prepare them for the wagon trains.

We lived near the Pawnee Rock where Kit Carson fought many a battle with the Indians. As a boy my playmates and I spent many hours on this famous rock “playing Indian” and even as a child I was attracted to Indian music and songs. I was able to begin to collect Indian themes and to color them with harmony. My brother after his graduation from a medical college took up practice among the Indians and married into the race. I used to visit him at different times and once went on the Crow Reservations. I met a German scientist who pointed out to me that right here in this country there was so much very new and original thematic material for the composer. It was he who made me think that some day our native Indian themes would form a part of the warp and woof of American music, as old Hungarian melodies have been woven into the texture of musical Hungary. I have melodies and records of material to furnish hundreds of composers themes. And it is my ambition to put this out in such a way that the musician who will make the sacrifices at this time to come here and harken to the real call of the wild will have material to give to posterity.

There is a term with the Indian—anything that is “good medicine” is all right. The Indian seems to credit me with the power to give “good medicine.” I gained their confidence and this once gained opened the flood gates of their melodies. Strange to say American singers were a little slow to realize the beauties of this material. When such an artist as Julia Culp came to America, she saw at once the value of the genuine Indian material when artistically arranged and placed a group of three of my songs on her program.

The very fact that Indian music is of such spontaneous, natural origin, that it is not a contraption or an artificial invention, makes it the hardest folk music. It comes right from the heart of nature and this gives it a classical feature which likewise makes it enduring in character and style. The Indian sings all his songs entirely in unison, he has no harmony except occasionally accidental harmony.

In 1913 the following singers: Standing Buffalo, Beaver, War Bonnet, Hand a Deer, Buckskin Star, Mountain Arrow and Black Bird, sang for me the following songs, in one single evening at the Pueblo near Taos, N. M.: “Sundown Song,” “Buffalo Dance Song,” “Deer Dance Song,” “Hand Game Song,” “Turtle Dance Song,” “Visitors Returning to the Estufa,” “Willow Dance Song,” and “Pueblo” Spring played on a flute.

These same singers sang songs they had heard from the following tribes:

Ute, “Squaw Dance Song”; Arapahoe, “Owl Dance Song”; Sioux, “War Song”; Navahoe, “Washing Song,” and three personal Love Songs.

Interesting Legends

This shows the variety of just one group of songs in one tribe. It also shows their liking for the songs of other tribes. From the above it has been possible for me to harmonize only five as I have not had time on account of the vast amount of material I have from other tribes. It is very easy to see how readily such themes could be swept away by the course of civilization, in comparatively few years. They all would have been gone were it not for the splendid efforts of such people as Carlos Troyer, Alice Fletcher, Alice Densmore, Natalie Curtis, La Hesche, and other fellow-investigators and collectors who have saved many of them. The Indians have legends about many of their songs. Here is an interesting one told by Buckskin Star:

“A party of Arapahoe hunters were camped in the Castillia canyon in northern New Mexico in the early days when the Indian tribes were at war with one another. Nearby were camped a band of Utes. The Arapahoes were aware of the war-like intentions of the Utes and during the night built up a wall of rocks around them for protection, working and singing at the same time. During the night a party of Utes crept up and learned their war song. The next day the fight took place, the Arapahoes being wiped out. In after years the Utes visited tthe (sic) Pueblo Indians near Taos and taught them their songs. Afterward the Arapahoes made a visit to the Pueblos and they heard their songs and were very indignant and wanted to know how they came to know them. Finally they discovered the reason and made friends with them, and to-day when tribes visit each other it is the custom for each to teach the other their songs.”

I have often noticed this among tribes. For special ceremonies there are special songs and special singers, there are certain songs which other singers are not permitted to sing. There is no singing by all members of the tribe like our congregational of community singing. The Indians who have made records for me have been selected by the leaders and these leaders have been very particular in selecting their singing groups. I have come to this conclusion—Indians either sing or they do not sing. They seem to have singing cliques. Those who do not belong to the clique do not participate. Of course, individuals have their own songs and very often an individual will have only one song, and again, I have had different flute players play into a dozen records the same song. He played only one song until he became a master of it. One Pueblo Indian I knew played a certain plaintive melody and adapted this to all conditions of his life. It seemed to be his spiritual medium and expressed his whole life in one song.

Certain of the native composers of the present time will take some of our hymns, such as “What a Friend I have in Jesus,” and adapt it to the Indian fashion. Davis, a Creek Indian, once sang this, hymn for me as sung in our churches and then sang it in Indian fashion.

In recent years it has been my privilege to have a number of Indian protegées who have decided musical gifts. I have given them opportunities to go on the Chautauqua circuits and concert platforms to give programs of their music. It is my missionary purpose to make the art and music of the Indian understood by the white people of America. I am interested in all talented Indians and, in my limited way, will do all I can to make them understood and at the same time help them to compete with other races. I have known some very fine Indian musicians, but I have never encountered one that seemed to possess the qualities to do for his race what Coleridge-Taylor did for the negro. Song is a spiritual part of the Indian. They like modern music because it seems a kind of tonic for them and something to taste and use, but not as a necessary medium of life.

Watahwasso’s Art

Watahwasso and Tsianina are remarkable Indian singers who have had splendid success in various parts of the country. Watahwasso has given so many programs of my own songs that I would feel a little delicate about speaking of her beautiful art and progress in recent years. She is a real Penobscot, with a glorious voice and understanding of Indian life. Oyapela, a Creek girl, is the foremost exponent of the myths and legends of her tribe. Te Ata is a Chececha girl. She is the Pavlova of the race, dancing the interpretative and historical events of her people. Pejawah is a Miami Indian and is the greatest violinist of the race. Willliam (sic) Reddy is an Alaskan Indian and is their foremost cellist. Paul Chilson is a Pawnee and has an exceptional tenor voice. Robert Coon is a full-blooded Sioux Indian and has played the great Sousaphone for years in the Sousa Band with fine artistic satisfaction to the conductor. Sousa, by the way, is giving a great deal of splendid attention to Indian music during this past year and has had upon a great number of his programs the Indian Rhapsody, composed by Preston Ware Orem, upon the themes which I gave him. Edna Wooley was brought up among the Indians on their reservation and has sung their songs from her infancy and now is interpreting many of my own songs in concerts. She sings in Sioux and has been coached by many Sioux singers and musicians.

The voices of Indian men are remarkably developed. They often start their songs as high as high C and end two octaves below. Most of the voices are basso and baritone in quality, the high notes are not falsetto notes. They sing with pure open vowel syllables like Hi-ya and hay-yah and Ho-ya-ho. Most Indian gongs (sic) could be divided into the following groups: War Dance Songs, Spiritual Songs, Society or Folk Songs of Clans, Pleasure Dance Songs, Game ‘and Gambling Songs, Flute Melodies, Ceremonial Songs and Love Songs.

While the Indians are divided into tribes and while these tribes are often radically different, it is not generally known they have a common means of communication—this is a sign language, by which an Indian from the plains of North Dakota could communicate with an Indian from the Everglades of Florida. The Indians also have powerful voices. I have heard a group of 18 or 20 Crows singing in unison 8 or 10 miles away. This was in a temperature of 20 degrees below zero, when sounds are readily communicated. The Indian very frequently sings his songs to syllables like vocalises or nonsense rhymes. Rarely, except in his love songs, does he use words. The song is dedicated to a certain purpose and he sings these monosyllables with quite as much enthusiasm as though they were real words. Naturally the great interest now being taken in Indian music is exceedingly gratifying to me. The many fine composers, such as MacDowell, Cadman, Arthur Nevin, Carl Busch, C. S. Skilton, Eastwood Lane, Arthur Farwell, H. W. Loomis, Homer Grün and others, who have given attention to Indian music, have accomplished splendid things; but, really, when one reviews the field, it is only to stand amazed at the extent of its possibilities.