By the Great Russian Pianist-Teacher

ALEXANDER SILOTI

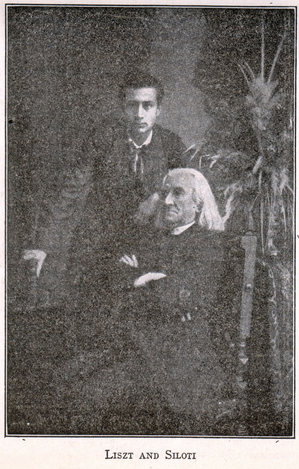

[Editor’s Note.—The tragic end of Siloti, who recently, according to report, dropped dead from starvation in the streets of Moscow, ends the career of one of the greatest of present-day Russian pianists. This very gifted man was a cousin of Rachmaninoff and a member of a Russian noble family. He toured America a number of years ago, and astonished everyone by the phenomenal facility of his technic. Very tall and very spare, the notes seemed to rain out of his long fingers almost without visible effort. Siloti was born at Charkov, Russia, in 1863. He was a pupil of the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Tschaikowsky and both of the Rubinsteins. Later he spent three years with Liszt. Then he became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory, and had many distinguished pupils. Siloti was one of the most devoted of the Liszt pupils, and Liszt was equally devoted to him. This article has been extracted from the complete authorized English translation of “Siloti’s Memories,” by Methven Simpson, which is published in book form..]

How Rubinstein Taught and Played

IT was finally settled that until I went abroad (my journey being planned for the spring of 1893) I should take advantage of Anton Rubinstein’s offer to give me lessons each time he came over to conduct the symphony concerts at Moscow—a task he had undertaken as a tribute to his brother’s memory. I heard that Rubinstein wished me to prepare the following works for my first lesson, which was to be in six weeks’ time:—Schumann’s Kreisleriana, Beethoven’s Concerto in E flat and the Sonata op. 101 in A, as well as Chopin’s Sonata in B minor. As he knew that I had played none of these things before, it was, to say the least of it, innocent on his part as a pedagogue to set so formidable an array of pieces to be learnt in six week. However, by dint of slaving seven or eight hours a day I did actually master them as far as the notes were concerned.

How well I remember that first lesson! Rubinstein had told me to bring Kreisleriana. Armed with this I arrived, expecting to be alone with him, but I found myself confronting about fifteen elegantly dressed ladies. I was greatly surprised, and felt nervous at having to take my lesson under such unsuitable conditions, particularly as I had only prepared the music mechanically. I must have behaved as if I were on the verge of a precipice, or as if I had received the death sentence. I certainly sat down feeling like a condemned criminal. “Play,” said Anton Rubinstein curtly, and I began, expecting him to stop me after the first number, and make some remarks. Not so, however. He said nothing, but fidgeted in his chair, turning from one side to the other, and running his fingers through his mane. Instinctively I felt that my fate was sealed. I went on playing with despair in my soul, convinced that I was lost, whatever I might do. I finished—silence! Suddenly Rubinstein asked, in a voice that was both stern and angry, “What is it you have been playing?” I sat still, and wondered why he had asked me. Did he not know the piece? As I made no reply he repeated the question, raising his voice. I then told him the name of the piece in a subdued tone.

“I know that, but what else?” he said. Then I remembered about the violinist, Kreisler, and said, “Schumann wrote this in honor of his friend Kreisler.”

“And why did Schumann not write a ‘Rubinsteiniana’ or a ‘Silotiana’? ”

At this I was absolutely nonplussed. Smoothing his hair again with a pretty gesture, he proceeded: “Because Kreisler was a wonderful man who possessed great poetical feeling, combined with a tremendous amount of ‘temperament.’ What you have to do is to play so that everybody realizes this.” Then, coming to the piano, he played as perhaps he had rarely played in his life before. Not that one could learn anything from it—I, as a pianist, did not exist for him, or, if I did, no more than if I had been a pile of rubbish in a corner of the room. The effect, I remember, was to make me feel: “Let me alone; I shall never study music any more.” All the same, insignificant as I was made to feel, I was offended. I recalled the method of Nicolas Rubinstein, which was to play to his pupils in such a way that they could realize the ideal he set before them. He always took into consideration the amount of talent each one possessed, and played so that the pupil never lost hope of being able some day to play as well as he did. The better the pupil, the better Nicolas Rubinstein’s playing.

I had other lessons of the same order from Anton Rubinstein, and as I look back they seem like a nightmare even now. I felt that he was absolutely indifferent to what I played or how I played. There was naturally no question of enjoyment, either for him or for me. He did not actually teach me anything. He only gave a super-inspired rendering of the music, and if the desire to learn was not killed in me it was due to my happy disposition which allowed me to regard these lessons as a temporary evil. Zvérieff, I remember, felt the same about them; after each lesson he talked to me in a peculiar way, as if he were making excuses for having made me study under such a master.

Liszt’s Wonderful Hospitality

Liszt’s Wonderful Hospitality

I packed up my belongings—not for my new quarters, but for Russia—and, taking with me Chopin’s Ballade in A flat, I went to Liszt for my lesson. As I approached the house the same sinking sensation which I had experienced at table came over me again, and I went in to my lesson as to a final ordeal before I started back to Russia. Liszt said good-morning to me very kindly. There were about twenty-five pupils present. Somebody played something—I do not remember what it was—then came my turn. I sat down and began the Ballade, but I had only played two bars when Liszt stopped me, saying:

“No, don’t take a sitz-bath on the first note.” He then showed me what an accent I made on the E flat. I was quite taken by surprise.

“Si, signore, si, signore,” said Liszt in Italian, smiling a trifle maliciously. I continued playing, but he stopped me several times and played over certain passages to me. When I got up from the piano I felt bewitched. I looked at Liszt, and was conscious of a gradual change in myself. My whole being became suffused by a glow of warmth and goodness, and by the end of my lesson I could not believe that, only two hours before, I had packed my things and wanted to run away. I left Liszt’s house a different being, and was convinced that I should, after all, stay and study with him. All my trouble—the feeling of loneliness and helplessness, arising from my ignorance of the language—flew away as if at the touch of a magic hand. I had become all at once a man who knew his own mind; I realized that there was a sun to whose rays I could turn for warmth and comfort.

List’s (sic) Manner of Giving Lessons

To describe Liszt’s lessons in such a way as to give an idea of his personality would be impossible. It is necessary to see certain things and certain people if one would have a clear impression of them. There were thirty or forty of us young fellows, and I remember that, gay and irresponsible as we were, we looked small and feeble beside this old man, shrunken with age. He was literally like a sun in our midst; when we were with him we felt the rest of the world to be in shadow, and when we left his presence our hearts were so filled with gladness that our faces were, all unconsciously, wreathed in rapturous smiles.

The lessons took place three times a week—on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays—from four to six o’clock. Anybody who wished could come and have a lesson without paying a farthing. Liszt remembered his own desire, when quite a boy, to enter the Paris Conservatorie, and the refusal to admit him on the part of the director (Cherubini) because he was a foreigner. This refusal, he said, made such an impression on him that he vowed to himself that if ever he became a great musician he would give lessons without taking any payment. It was practically a condition that men should come to the lessons, not in frock coats, but wearing lounge jackets, and that ladies should be simply dressed—the idea being that the poorer pupils should not feel uncomfortable beside the richer ones.

Liszt’s lessons were of a totally different order from the common run. As a rule he sat beside, or stood opposite to, the pupil who was playing, and indicated by the expression of his face the nuances he wished to have brought out in the music. It was only for the first two months that he taught me in front of all the other pupils; after that I went to him in the morning when I was working at any specially big thing, and he taught me by myself. I always knew so thoroughly what I wanted to express in each piece of music that I was able to look at Liszt’s face all the time I was playing.

No one else in the world could show musical phrasing as he did, merely by the expression of his face. If a pupil understood these fine shades, so much the better for him; if not, so much the worse! Liszt told me that he could explain nothing to pupils who did not understand him from the first. He never told us what to work at; each pupil could prepare what he liked. All we had to do when we came to the lesson was to lay our music on the piano; Liszt then picked out the things he wished to hear.

There were only two things we were not allowed to bring: Liszt’s 2nd Rhapsody (because it was too often played) and Beethoven’s Sonata quasi una fantasia which Liszt in his time had played incomparably, as was afterwards proved to me. Neither did he like anyone to prepare Chopin’s Scherzo in B flat minor, which he nicknamed the “Governess” Scherzo, saying that it ought to be reserved for those people who were qualifying for the post of governess. Everything else of Chopin’s, particularly his Preludes, he delighted in hearing. He insisted on a poetical interpretation, not a “salon” performance, and it irritated him when the groups of small notes were played too quickly, “conservatorium-fashion” as he called it.

A Second Section of this Very Interesting Article will Appear in THE ETUDE for August