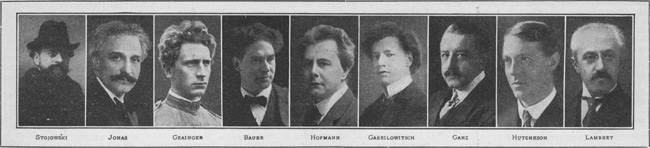

A Historic Conference Conducted Through the Co-operation of a Group of the Foremost Pianists of the Day in the Interests of ETUDE Readers

HAROLD BAUER OSSIP GABRILOWITSCH RUDOLPH GANZ

PERCY GRAINGER JOSEF HOFMANN ERNEST HUTCHESON

ALBERTO JONÁS ALEXANDER LAMBERT SIGISMUND STOJOWSKI

ALBERTO JONÁS ALEXANDER LAMBERT SIGISMUND STOJOWSKI

In march (sic), 1918, The Etude invited a group of very distinguished pianists (several of whom, during the past few years, have given a part of their time at least, to the practical problems of teaching the art of piano playing), to a private dinner held at Claridge’s Hotel, in New York City. One or two were good enough, though prevented by absence from the city from accepting the invitation, to send in their opinions upon the above subject after the dinner.

The artists participating represent many of the most brilliant, experienced and active minds in the field of sincere pianistic study. The Etude is especially proud of the outcome of the conference for it is not overstating the facts to say that it is of historical significance. An expert stenographer was present and took copious notes, from which the following was prepared.

It is impossible to present all the views given in this one issue, and the discussion will be continued in other issues—other artists not included in this issue being included in later issues.

The Etude desires to call the attention of its readers to the wide experience represented in this discussion. The artists have been trained in different schools by teachers of many different inclinations. All the best traditions from all of the different art centers of this country and Europe are represented. The discussion followed the plan of considering the piano and its art: (a) from the standpoint of the instrument itself; (b) from the standpoint of the interpreter; (c) from the standpoint of the composer for piano.

The evening opened with a slight digression from the subject, dealing with the very fortunate opportunity that music and musicians have had, to serve in the great war. Many of the artists had taken an active part in playing at concerts given in the camps and for war benefits.

EDITOR OF THE ETUDE

The present seems a very fortunate time in which to conduct such a conference as this, since never before in the history of the world has the need for music been more apparent to thinking men. The Etude has secured a series of articles and statements from illustrious men and women, including General Pershing, General Hugh Scott, Lyman Abbott, Henry C. Van Dyke, Samuel Gompers, John Philip Sousa, Ida M. Tarbell, Dr. Anna Shaw, Thomas Edison and others, emphasizing the special need for music in war time. It is most important that the interest in our art be actively maintained by its leading workers at this time.

MR. ALEXANDER LAMBERT

There was a letter in the New York Times yesterday that was very interesting. It outlined the pressing need for music of the right kind during the war. It is very inspiring to see the manner in which our leading musicians have been only too anxious here and in Europe to give their services. The fighters need the relaxation of music, and those at home likewise. On the whole, the art will receive an altogether unexpected impetus, due to war conditions, since the public has been presented with an opportunity to realize the serious need for music in times of great crisis. Those who, heretofore, may have thought music inconsequential, or unnecessary, will have their eyes opened.

MR. ERNEST HUTCHESON

As far as I have read, the military and naval, authorities have done everything in their power to encourage the employment of music wherever groups of soldiers are gathered together. The soldiers here and abroad appear only too eager to grasp everything in the way of musical inspiration and encouragement. Here in New York, at the Columbia University Hospital for Wounded Soldiers, they have been trying, among other things, the use of music as a therapeutic agency—particularly in cases of shell shock. Musicians should take time by the forelock and consider conservatively the possibilities of their art in helping such cases. One loses one’s sense of proportion in the midst of such vast war preparations. I am comforted when I think that any war, however disastrous, is but an incident in the history of the world, and that art, including the beautiful art to which we are devoting our lives, is something ultimately of far greater importance and permanence. Think of the wars that have come and gone while the masterpieces of Purcell, Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, and other composers live in triumph. Music, the most ethereal of the arts, is also one of the most enduring. Wars carry away cathedrals, libraries, great paintings, but music always survives.

RUDOLPR (sic) GANZ

While this is not yet the main subject of our discussion, I am very much impressed with our interesting overture. The war has, indeed, brought out new phases in music. A few weeks ago, at one of the soldiers’ camps where I played, the audience was remarkable in every way. They wanted “encores,” and demanded only the best there is in piano literature. Compare the new American Army with the army of other days. Here are men of all walks in life. Some with as highly cultivated taste as one would encounter in a Carnegie Hall audience. It seemed a little surprising when, at another camp, I asked for requests, to have some of the men call for the Symphonic Etudes of Schumann. To me, the musical achievements in many of the camps is nothing short of amazing. I am sure that the life in most camps has been made infinitely better for the men owing to the musical and other entertainments and opportunities to sing.

SIGISMUND STOJOWSKI

The interest of all manner of artists in America and Europe in supporting humanity’s great battle in every possible way will not be forgotten. As a Pole, I am proud to point to the tireless labors of my great fellow-citizen, Ignace Jan Paderewski, whose personal sacrifices at this time are already historic, That musicians have been able to play such a significant role in the greatest hour in the history of the world, is significant of the world’s progress. While music has been promoted from a mere object of amusement or luxury to a factor in education, character, civilization— the musical artist himself, the “servant” of Ioccenes of yore, the “amuser” of crowds in later days, is at last understood to be a full-fledged “man” with a wide range of interests and knowledge, a heart vibrant with human sympathy and generosity—a “man” truly qualified to “lead” because of his high intellectual achievements and purposes.

EDITOR OF THE ETUDE

The discussion of the subject of our conference has commenced a little in advance. Here is a letter from Mr. Percy Grainger, who expected to be here to-night, but is unable to do so, owing to his service in the army. Before reading his letter it may be interesting to consider some of the possibilities of our subject, “Has the Art of the Piano reached its zenith or is it capable of further development?” The development of the piano as an instrument has been amazingly slow in many ways. Yet it has been a development. It is an instrument which, in comparison with the violin, is comparatively new. The famous Brescia violin maker, Gasparo da Salo (Bertalotti) died in 1609; the Maggini’s, respectively, in 1640 and 1680; the Cremona family, of Amati, passed on, respectively, in 1611, 1638 and 1684; the three Stradivari in 1737, 1743, 1742, and the Guarneri family, respectively, in 1695, 1730, 1745. The work of the great Italian violin makers is more sought in this day than ever. None of the violins of present-day makers are conceded to be their superior and the zenith of the manufacture of the instruments was evidently reached nearly two hundred years ago. This fact is so well established that there is no gainsaying it. On the other hand, what of the piano? Hundreds of years passed from the time of the invention of the monochord before the first keyed string instruments were in use, and then more hundreds of years before the advent of the first piano of Bartolomeo Cristofori, which probably appeared first about 1709 or a little earlier. The two instruments of Cristofori, which have been preserved (one of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in this city) are so radically different in many ways from the modern grand pianoforte that it is difficult to think of the bridge between them.

Since the invention and the improvement of an instrument often marks a change in the progress of the art of the instrument it is perhaps wise for us to consider the possibilities of the instrument at the start. We all know, for instance, how the invention of the saxaphone and other instruments of Adolphe Saxe have affected some phases of modern instrumentation. Is it not within the scope of this discussion to ask whether the piano may not advance in future years along different lines which will affect the art of the instrument, or has the instrument attained a form which is not likely to be changed to its advantage in years to come. Mr. Grainger, as I have said, has already sent in a few lines. He seems to have devoted a great deal of thought to radical changes in the instrument in the future, and for that reason it may be best to read his communication here. We are all familiar with the many new sound effects which he has introduced in his orchestral works.

PERCY GRAINGER

“Has the art of the piano reached its zenith or is it capable of further development?” Whether the piano in its present form has reached its zenith as a solo instrument I cannot tell; I have no feeling one way or the other as regards that aspect, but I should like to point out that it is only at the beginning of its possibilities as an instrument in the symphony orchestra and military band and as a unit in large chamber music combinations and only at the outset of its truly marvelous possibilities as a mechanically played instrument. But I do not consider the present form of the piano as FINAL. I have in my mind a sketch for a piano equipped with several manuals, each “manual operating hammers of different weights and degrees of softness and harshness. Such an instrument, if further provided with octave coupler stops like an organ and with electrically operating tremolo action like a piano similarly equipped that I heard in London some years ago would be a marvelous solo instrument (combining all the variety of the forerunners of the pianoforte, harpsichords, etc., with the glorious richness and volume of a modern grand pianoforte of the highest type) as well as a gold mine for symphony orchestra, small orchestra, military band and chamber music work.

The mechanically played possibilities of such an added-to piano would be just immense.

Then, there is another aspect of the piano and its keyboard. Percussion instruments, bells, marimbas, tubes, etc., will play an ever increasing goal in modern scores, I feel sure. But the full possibilities of these instruments will never be tapped until they are equipped with piano keyboard action, like the celesta. The piano keyboard will then be the “volapuk” or universal medium for some six to ten different percussion instruments which, together, will form a section in the orchestra just as important as are, to-day, the strings or the brass. There is, furthermore, no reason why all these various percussion instruments, each provided with innumerable octave-coupler and manual-coupler stops and the electric tremolo outfit above mentioned, should not be united together in one huge percussion-piano or percussion-organ, and in this leviathan piano, which would be a “complete orchestra in itself,” as well as an un-do-withoutable addition to the modern orchestra. Viewed from several standpoints, therefore, I consider the art of the piano as being very far from its zenith.

ALEXANDER LAMBERT

One feels like drawing a long breath after hearing of such an instrument as that. Whatever it might be it would not be a piano, but a kind of keyboard operated instrument of a different type. We already have instruments operated from a keyboard, like some of those to be heard in motion picture theaters, as well as electrically vibrated instruments of the choral-celo type, marvelous mechanical intruments (sic) to be sure, but in no sense pianos, they are instruments in a class by themselves, and they fill a special need for which they were built. It is not inconceivable that such an instrument will be combined with a large orchestra as, indeed, they are in some motion picture theaters where there are very large orchestras continually employed, and often with beautiful effect. But this only emphasizes the point that the piano is still the piano, and not anything but the piano. In my opinion the piano has long since found itself, that is, it has a well defined entity by itself, and that any radical change in the instrument will injure the art that has developed around it. While the modern pianos are different in some tonal effects from those of less tonal quantity from those of the days of Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin the character of the instrument is the same. True, the piano, because of its mechanical nature, does not have the endurance of the Cremona violin, but I insist that the best modern grand pianofortes are in spirit the same as the first instruments of Cristofori, that is, they are pianos and nothing but pianos. Since the time of Liszt, when the possibilities of the grand piano, as we know it to-day, were practically the same, I cannot see that there has been any advance except in certain refinements.

ALBERTO JONÁS

To me it seems idle to speculate on what the future may bring in the matter of further improvements of our modern pianos. In a series of three articles which I wrote for The Etude several years ago I pointed out that all improvements in musical instruments have originated, not with the manufacturers, but with the composers or with the players of instruments. It is desire which brings about a result. Therefore, it seems to me, that instead of speculating in which manner the piano may be improved we should simply find out what it is that we still wish the piano to possess. Evidently, and foremost, among these desired improvements, is the ability to sustain for any length of time and to increase at will the tone of the piano. Time will show whether this can be accomplished without losing that which forms one of the principal charms of the piano: the purity and the comparative brevity of the tone. Inasmuch as the trend of human progress seems to be more in the direction of science than,—alas! if this should turn out to be true— of art, it is possible that the piano of the future will in truth be a whole orchestra manipulated by one single player.

SIGISMUND STOJOWSKI

I find myself in complete agreement with Mr. Lambert. Some fifteen years ago I met a clergyman in Berlin who was going about boasting of a musical invention that he claimed would revolutionize the musical world. It was nothing more or less than a piano to which three trombones had been added. I hardly think that would be an improvement in the piano. To me it seems most important that all those who are in any way connected with the study of the piano should revere their art as an art. First, the piano as an instrument; second, the interpretation of the instrument, and third, the compositions that have been evolved from the instrument and for the instrumen (sic) (like the idiomatic works of Chopin and Debussy) all represent a wonderful and distinct art achievement. Is it possible to expect the art of the piano to go beyond its real sphere already clearly outlined by its significant past?

This conference will be continued in the next issue of The etude with some remarkable facts. All the pianists mentioned at the head of this article will participate in the conference before its conclusion.