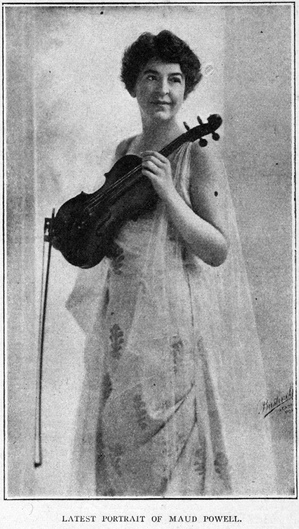

An Interview with the Most Famous of American Violinists

MAUD POWELL

Secured expressly for THE ETUDE by Charles P. Poore

[Editor’s Note.—Miss Maud Powell, the greatest violinist of her sex, in a native of Peru, Ind. Wm. Lewes, of Chicago, was her early teacher; afterward she studied with Schradieck in Leipsic, Dancla in Paris and, Joachim in Berlin. She has made extensive concert tours in most parts of the civilized world, and was the first player to introduce the violin concertos of Arensky, Dvoràk, Saint-Saëns (C min.) and Lalo (G maj.) to America. She has made some very effective transcriptions of various songs and piano pieces for the violin, and has been a contributor to The Etude from time to time. In 1904 she married, and is known in private life as Mrs. H. Godfrey Turner. Her success as a violinist has been a very great source of inspiration among girls who have taken up the study of the violin; indeed, her influence in this particular way has been so wide-reaching that one could scarcely overestimate it.]

[Editor’s Note.—Miss Maud Powell, the greatest violinist of her sex, in a native of Peru, Ind. Wm. Lewes, of Chicago, was her early teacher; afterward she studied with Schradieck in Leipsic, Dancla in Paris and, Joachim in Berlin. She has made extensive concert tours in most parts of the civilized world, and was the first player to introduce the violin concertos of Arensky, Dvoràk, Saint-Saëns (C min.) and Lalo (G maj.) to America. She has made some very effective transcriptions of various songs and piano pieces for the violin, and has been a contributor to The Etude from time to time. In 1904 she married, and is known in private life as Mrs. H. Godfrey Turner. Her success as a violinist has been a very great source of inspiration among girls who have taken up the study of the violin; indeed, her influence in this particular way has been so wide-reaching that one could scarcely overestimate it.]

Violin players to-day, generally speaking, group themselves in two classes, or schools. The psychology of these two schools lies deeper than the principles of the Belgian School of violin, placing or the French School, which have for so long held sway over the violin world. The two classes I have in mind are concerned with questions fundamentally more important than mere methods of holding the bow or the development of the left hand. They have to do with mental attitudes. One of these two schools is based on the theory that the performer of the music is of greater importance than the music itself—that the music is merely the medium through which the performer may play upon the emotions of his hearers and win plaudits as a virtuoso. It is a theory of self-exploitation.

The principles of the other class are founded in the belief that the power of the best music infinitely transcends the boldest flights of the virtuoso—that the function of the artist is purely interpretative: that the best he can do is to mirror faithfully the spiritual content of the music he plays.

One school develops and stresses the spectacular, the other endeavors to interpret the music in accordance with the spirit of the times in which it was written and the composer’s intent. One depends for effect upon personal display, the other upon musicianship plus vision. In the latter category are the world’s greatest violinists, among whom, if I may judge by a single hearing, we shall include to-day Jascha Heifetz. All that Heifetz does apparently shows that he is more concerned with the music than with his own self-exploitation. His tremendous vogue is due to sincerity of spirit joined to extraordinary ability.

In what I have said, I do not want to be understood as implying that violinists willfully choose the wrong, less noble course. Self-advertising is quite characteristic of our American life, and influences our art as well as our business. I have laid stress upon these differences in mental attitude solely through a desire to do something helpfully constructive by way of definite suggestion.

The Significance of the Accompaniment

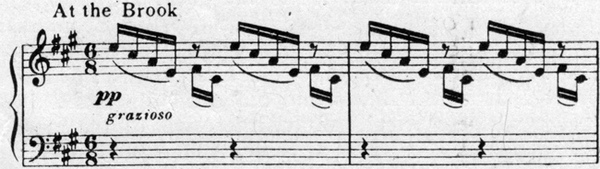

Speaking of violin literature: it is always very helpful to young students, and, I may add also to audiences, to consider the pieces played as duets for piano and violin rather than as violin solos. Occasionally a composer writes a pure melody so complete in itself as to need no accompaniment. Such is perhaps Schumann’s Traumeri, although even its beauty is enhanced by the lovely accompaniment. But more often the melody tells only half the story, as in characteristic pieces or so-called program music. A pretty characteristic piece that I often play is At the Brook, by Boisdeffre.

Often when I am playing informally I describe the music in a few words. Of this composition I say something like this—“The piece I am to play now is really a duet, so you will have to listen very carefully to both parts. If you want to know where the brook is I think you will find it in the piano; I am just a little skiff floating on the surface, or perhaps a gleam of sunshine playing with the ripples.” In other words, the piano part (I was going to say accompaniment, but the word is misleading) is so descriptive that the melody would be meaningless without it.

Often when I am playing informally I describe the music in a few words. Of this composition I say something like this—“The piece I am to play now is really a duet, so you will have to listen very carefully to both parts. If you want to know where the brook is I think you will find it in the piano; I am just a little skiff floating on the surface, or perhaps a gleam of sunshine playing with the ripples.” In other words, the piano part (I was going to say accompaniment, but the word is misleading) is so descriptive that the melody would be meaningless without it.

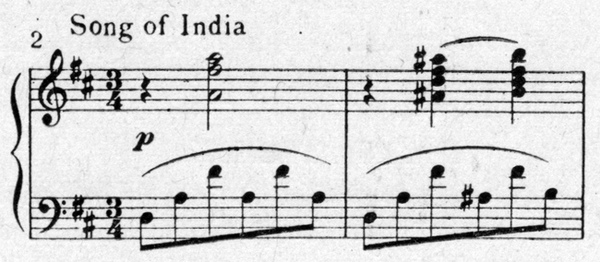

In Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Song of India (Chanson d’Indoue), a piece that carries one straight to Eastern climes, the composer establishes a languorous mood through the mesmerizing influence of the monotonous piano part, with its insistent repetition of the same bass note throughout, followed always by the rocking figure in eighth notes.

In Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Song of India (Chanson d’Indoue), a piece that carries one straight to Eastern climes, the composer establishes a languorous mood through the mesmerizing influence of the monotonous piano part, with its insistent repetition of the same bass note throughout, followed always by the rocking figure in eighth notes.

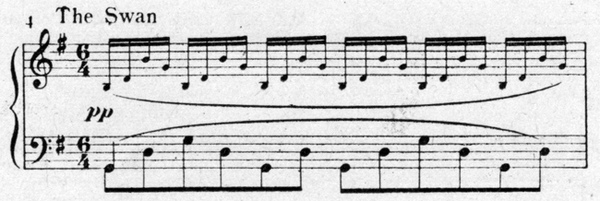

In Souvenir, by Drdla, the figure, reiterated in the violin, and echoed by the piano, suggests the mind’s workings—memory recalling one thought with little variation, in endless reiteration. In Saint-Saëns’. The Swan the effect of graceful line and pride of motion (in fact, the mental picture of a floating swan) is achieved largely through the clever treatment of the piano part, which suggests the mirror-like yet plastic surface of water, thus throwing into relief the gentle melody of the violin which in imagination portrays the swan’s graceful movements.

In Souvenir, by Drdla, the figure, reiterated in the violin, and echoed by the piano, suggests the mind’s workings—memory recalling one thought with little variation, in endless reiteration. In Saint-Saëns’. The Swan the effect of graceful line and pride of motion (in fact, the mental picture of a floating swan) is achieved largely through the clever treatment of the piano part, which suggests the mirror-like yet plastic surface of water, thus throwing into relief the gentle melody of the violin which in imagination portrays the swan’s graceful movements.

A fine example of a violin solo which should be treated as a duet is Handel’s Largo. The melody alone could never create that definite impression of exaltation which a good performance of this piece invariably produces. But atmosphere is created by the simple chords of the piano—these establishing a mood at once. They are like the mighty law of gravitation holding the universe together, even each little star moving in its prescribed place. Or, they move like Fate, itself, ever onward, inevitably, inexorably, to a definite goal, carrying a triumphant soul (the melody) with them.

A fine example of a violin solo which should be treated as a duet is Handel’s Largo. The melody alone could never create that definite impression of exaltation which a good performance of this piece invariably produces. But atmosphere is created by the simple chords of the piano—these establishing a mood at once. They are like the mighty law of gravitation holding the universe together, even each little star moving in its prescribed place. Or, they move like Fate, itself, ever onward, inevitably, inexorably, to a definite goal, carrying a triumphant soul (the melody) with them.

It is especially necessary in these days for violinists to develop a faculty of listening to the whole harmonic structure of compositions in order to cultivate a sense of ensemble; for contemporary composers of music for violin and piano, more and more, rely upon the rich colorful complex harmonizations that have been developed within the past few years, for creating atmosphere; and unless one has learned to listen intelligently and can analyze the function that harmony plays, an adequate, effective interpretation is impossible, for the violinist will fail certainly to attain the balance of parts. Modern impressionistic music demands of the performer that he shall have power of visualization and a well-developed color sense. He must have in his own mind a clear concept of the picture the composer limns. Modern composers paint, as on canvas, with a broad brush and with bold color; and the artist must have the breadth of vision to see the work in its total effect. A good example of this type of music is Sibelius’ Concerto (First Movement). This is a work to tax the technical resources of the artist and his imagination.

As a homely comparison, modern music for even violin and piano may well be likened to a complicated salad, in which the ingredients are so cleverly blended as to be undistinguishable except to an epicure. They defy analysis; they bear not the least resemblance to the simple salads of former days. To intelligently enjoy (analyze) these highly seasoned concoctions really demands an educated taste. To carry out the comparison—the simple salads are like the older classics, direct and simple in construction, with a simple well-defined interrelation of parts; modern music is highly seasoned and complex (full of bizarre chord combinations and weird harmonizations), and the enjoyment of it demands power of analysis, with a highly developed color sense. I have said nothing about violin technic. To discuss technic in detail would require the space of another article; but this much is apropos of what I have been saying—that without a technic more than adequate for the music being studied, a rapid development of interpretative power is difficult. I like to compare the violinist, in the development of his technic, with the base ball player or the golf player. To both, “good form” is a sine qua non. Without technic every exciting moment of the game finds the contestant undone. But in ball playing technic is the end of all—the final test. In the life of the artist technic is necessary, but not for itself; he needs technical accomplishment to enable him not alone to meet the excitement of a public performance with equanimity, he needs it also so that while his spirit may soar to the clouds, and like Prometheus bring down fire from heaven to mortals, his fingers and bow may remain on the terra firma of his instrument to faithfully interpret the inspired message.