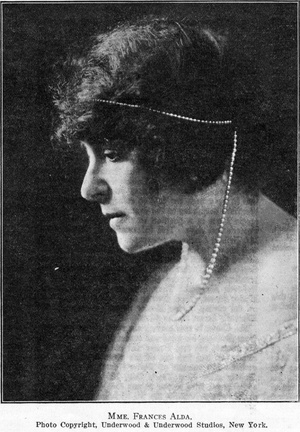

From an interview secured expressly for The Etude, with the noted prima donna soprano

of the Metropolitan Opera Company

(Editor's Note.—Mme. Frances Alda, like Mme. Melba, was born in Australia. Her studies in music started at an early age and culminated in a course with the late Mme. Marchesi in Paris. Her début was made at the Opéra Comique in Paris, in 1906, in the opera of Manon. Thereafter she sang in leading European Opera Houses until her début in America, in 1909, in the rôle of Gilda in Rigoletto. Her success at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York has been brilliant and persistent. Later she became the wife of Mr. Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the most successful of all impresari in the history of American opera. Her close association with operatic affairs in Europe and in America make this interview of special value.)

"To the girl who aspires to have an operatic career who has the requisite vocal gifts, physical health, stage presence and—most important of all—a high degree of intelligence, the great essential is regular daily work. This implies regular lessons, regular practice, regular exercise, regular sleep, regular meals—in fact, a life of regularity. The daily lesson in most cases seems an imperative necessity. Lessons strung over a series of years merely because it seems more economical to take one lesson a week instead of seven rarely produce the expected results. Marchesi, with her famous wisdom on vocal matters, advised twenty minutes a day and then not more than ten minutes at a time.

"For nine months I studied with the great Parisian maestra and in my tenth month I made my début. Of course, I had sung a great deal before that time and also could play both the piano and the violin. A thorough musical knowledge is always valuable. The early years of the girl who is destined for an operatic career may be much more safely spent with Czerny exercises for the piano or Kreutzer studies for the violin than with Concone Solfeggios for the voice. Most girls over-exercise their voices during the years when it is delicate. It always pays to wait and spend the time in developing the purely musical side of study.

"More voices collapse from over-practice and more careers collapse from under-work than from anything else. The girl who hopes to become a prima donna will dream of her work morning, noon and night. Nothing can take it out of her mind. She will seek to study every imaginable thing that could in any way contribute to her equipment. There is so much to learn that she must work hard to learn all. Even, now, I study pretty regularly two hours a day, but I rarely sing more than a few minutes. I hum over my new rôles with my accompanist, Frank La Forge, and study them in that way. It was to such methods as this that Marchesi attributed the wonderful longevity of the voices of her best-known pupils. When they followed the advice of the dear old maestra their voices lasted a long, long time. Her vocal exercises were little more than scales sung very slowly, single, sustained tones repeated time and again until her critical ear was entirely satisfied, and then arpeggios. After that came more complicated technical drill to prepare the pupil for the floritura work demanded in the more florid operas. At the base of all, however, were the simplest kind of exercises. Through her discriminating sense of tone quality, her great persistence and her boundless enthusiasm she used these simple vocal materials with a wizardry that produced great prime donne.

"Marchesi laid great stress upon the use of the head voice. This she illustrated to all her pupils herself, at the same time not hesitating to insist that it was impossible for a male teacher to teach the head voice properly. (Marchesi herself carried out her theories by refusing to teach any male applicants.) She never let any pupil sing above F on the top line of the treble staff in anything but the head voice. They rarely ever touched their highest notes with full voice. The upper part of the voice was conserved with infinite care to avoid early breakdowns. Even when the pupils sang the top notes they did it with the feeling that there was still something in reserve. In my operatic work at present I feel this to be of greatest importance. The singer who exhausts herself upon the top notes is neither artistic nor effective.

"The American girl who fancies that she has less chances in opera than her sisters of the European countries is silly. Look at the lists of artists at the Metropolitan, for instance. The list includes twice as many artists of American nationality as of any other nation. This is in no sense the result of pandering to the patriotism of the American public. It is simply a matter of supply and demand. New Yorkers demand the best opera in the world and expect the best voices in the world. The management would accept fine artists with fine voices from China or Africa or the North Pole if they were forthcoming. A diamond is a diamond no matter where it comes from. The management virtually ransacks the musical marts of Europe every year for fine voices. Inevitably the list of American artists remains higher. On the whole, the American girls have better natural voices, more ambition and are willing to study seriously, patiently and energetically. This is due in a measure to better physical conditions in America and in Australia, another free country that has produced unusual singers. What is the result? America is now producing the best and enjoying the best. There is more fine music of all kinds now in a week than one can get in Paris in a month and more than one can get in Milan in six months. This has made New York a great operatic and musical center. It is a wonderful opportunity for Americans who desire to enter opera.

The Need for Superior Intelligence

"There was a time in the halcyon days of the old coloratura singers when the opera singer was not expected to have very much more intelligence than a parrot. Any singer who could warble away at runs and trills was a great artist. The situation has changed entirely to-day. The modern opera-goer demands great acting as well as great singing. The opera house calls for brains as well as voices. There should properly be great and sincere rivalry between fine singers. The singer must listen to other singers with minute care and patience and then try to learn how to improve herself by self-study and intelligent comparison. Just as the great actor studies everything that pertains to his rôle, so the great singer knows the history of the epoch of the opera in which he is to appear, he knows the customs, he may know something of the literature of the time. In other words, he must live and think in another atmosphere before he can walk upon the stage and make the audience feel that he is really a part of the picture. Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree gives a presentation that is convincing and beautiful, while the mediocre actor, not willing to give as much brain work to his performance, falls far short of an artistic performance.

"A modern performance of any of the great works as they are presented at the Metropolitan is rehearsed with great care and attention to historical detail. Instances of this are the performances of L'Amore di Tre Re, Carmen, Bohéme and Lohengrin, as well as such great works as Die Meistersinger and Tristan und Isolde.

Physical Strength and Singing

"Few singers seem to realize that an operatic career will be determined in its success very largely through physical strength, all other factors being present in the desired degree. That is, the singer must be strong physically in order to succeed in opera. This applies to women as well as to men. No one knows what the physical strain is, how hard the work and study are. In front of you is a sea of highly intelligent, cultured people, who for years have been trained in the best traditions of the opera. They pay the highest prices paid anywhere for entertainment. They are entitled to the best. To face such an audience and maintain the high traditions of the house through three hours of a complicated modern score is a musical, dramatic and intellectual feat that demands, first of all, a superb physical condition. Every day of my life in New York I go for a walk, mostly around the reservoir in Central Park, because it is high and the air is pure and free. As a result I seldom have a cold, even in midwinter. I have not missed a performance in eight years, and this, of course, is due to the fact that my health is my first daily consideration.