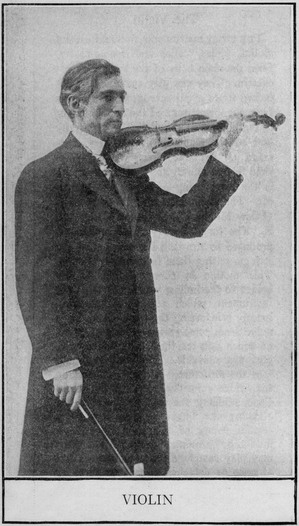

The string instruments, first and second violins, violas, 'cellos and double-basses, form the main body of the symphony orchestra. They can play sustained or detached tones at all speeds; their compass from the lowest tone of the double-basses to the highest of the violins is practically that of the piano keyboard; they command all dynamic effects from pianissimo to fortissimo; and their tone-quality is the least tiring of all to the human ear. The violin has four strings, tuned G (below Middle C), D (above C), A and E. The tone of all viol instruments is produced by drawing the bow across the strings, setting them in vibratory motion. This motion is communicated by the bridge to the hollow wooden body of the instrument, which acts as a resonator, greatly reinforcing the tone. A violin is made from some seventy pieces of wood, of which only ten, the bridge, fingerboard, etc., are movable. The rest are built into the structure. A "mute" placed on the bridge somewhat deadens the vibrations, muffling the tone if desired. By allowing the finger to rest lightly on certain points of the vibrating strings, flute-like "harmonics" are produced. One may play sustained tones on two strings at once or detached chords on three or four strings, this process being known as "double-stopping."

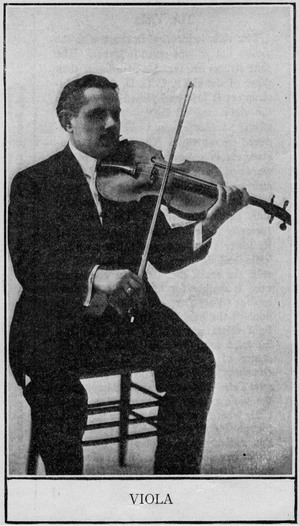

The viola is identical in shape with the violin, but is one-seventh larger. The four strings are tuned a fifth lower than those of the violin, C, G, D, A. The instrument is held and played the same as the violin, and all the bowing and other effects possible on the violin can be produced on the viola. The tone of the instrument is somewhat mournful; in the words of Berlioz, "The sound of its low strings is peculiarly telling, its upper tones are distinguished by their mournfully passionate accent." The viola was formerly the Cinderella of the orchestra; its lower tones overlapped those of the 'cello, and the upper those of the violins, with the result that the older composers used it mainly for "filling in" the harmonies. Very frequently the viola simply doubled the bass part, and where a very light effect was desired was (and still is) used as a bass instrument. An instance of this occurs in the Miniature Overture of Tchaikovsky's Casse Noisette Suite. Modern composers have given the viola a more prominent place, especially where a mournful quality is needed, though Méhul's attempt to replace violins entirely with violas in his opera Uthal was not a success. Elgar gives the viola a lovely solo in his Italian Overture, and others have done the same with excellent effect.

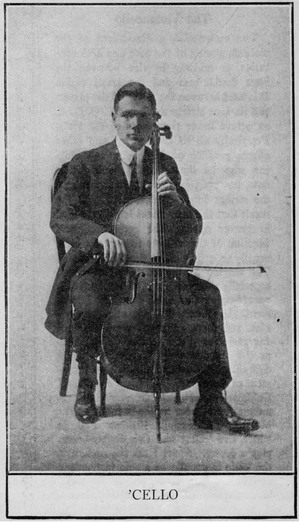

The violoncello, a descendant of the viola da gamba of the 16th and 17th centuries, is midway in size between the huge double-bass and the small violin. It is held between the knees of the player, and its four strings are tuned C, G, D, A, an octave lower than those of the viola. Practically all of the bowing and other effects possible on the violin and viola can also be done on the 'cello. The bow, however, is somewhat heavier and the strings longer and thicker, with the result that the instrument is better suited in graver music. The main orchestral function of the 'cello is to play the bass, usually an octave above the double-basses. The singing quality of its upper tones, especially those on the A string, makes it exceedingly valuable as a melody instrument. Frequently it sings above the violas, and there are many works famous for melodies given to the 'cellos, such as the andante from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, the second theme, first movement of Schubert's Unfinished Symphony, Goldmark's Sakuntala Overture, etc. A unique passage for 'cellos is found in the overture to Rossini's William Tell, in which five 'cellos and two double-basses play a septet. Apart from the orchestra, the 'cello is popular as a solo instrument, and indeed is second only to the violin among string instruments in this respect.

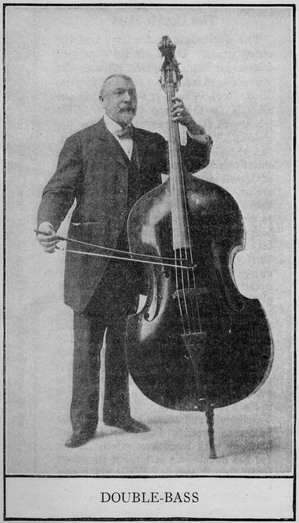

The double-bass is the largest of the string group. The older three-stringed instrument has now given place to the four-stringed instrument tuned in fourths, E, A, D, G. The E is the lowest E obtainable on the piano keyboard. This instrument is the foundation of the orchestra. To it is confided the bass part, and though in very loud passages it is sometimes reinforced by the tuba or the contra-bassoon, its deep, booming tones are usually adequate, and indeed must be used with discretion to avoid heaviness. In waltzes and two-steps, etc., the double-bass often plays pizzicato on the accented beat of the measure only. It is a somewhat tiring instrument to play, as the strings are long and thick, and the bow necessarily heavy, but it is capable of playing rapid passages. Gluck took advantage of its low rumble to imitate the howling of Cerberus, the hound-like guardian of Hades. Beethoven frequently gave the double-bass rapid passages as in the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony, and in the Pastoral Symphony. A famous Beethoven passage is the recitative in the Ninth Symphony. Berlioz, Dvorak, Tchaikovsky and others have divided the basses to produce three- or four-part harmony with lugubrious effect. Music for the double-bass is written an octave lower than it sounds. While not a solo instrument, concertos have been written for it by Dragonetti and Bottesini.

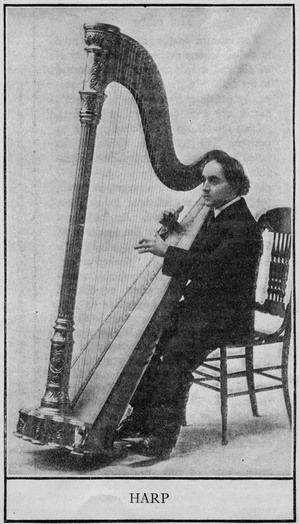

The modern double-action harp as used in the symphony orchestra has a compass of six and a half octaves, and is tuned to the scale of C flat major. Seven transposing pedals corresponding to the scale names are used to neutralize the flats, raising the strings a half-tone or tone as desired. The harp can, therefore, be tuned to all keys. The complicated mechanism renders the harp ill-adapted for rapid chromatic scale passages, and even for chromatic modulations unless these are carefully contrived. An additional "forte pedal" increases the loudness of the instrument. The tone quality of the harp is the purest of all "plucked string" instruments, and is very valuable whenever ethereal or poetic effects are desired. In a passage almost impossible to play, Wagner has used the harp for the flicker of the flames in his Magic Fire music; Gounod used it very effectively in the Garden Scene in Faust and again in that work for the heavenly ascension of Marguerite at the end. The word "arpeggio" suggests the kind of music best suited to the harp, but it can also produce solid chords, play an effective "glissando" and even sustain a legato melody piano-fashion. While the harp is one of the oldest instruments of the orchestra it has changed less in general structure than any other.

The glockenspiel, meaning in English "chime-bells," was originally a toy imitation of the Flemish carillons. It consisted of tiny little bells giving a fairylike effect. Handel used an instrument of this kind in his oratorioSaul, probably for the first time in a serious work. Mozart also employed one in hisMagic Flute, with charming appropriateness. The modern glockenspiel consists of a number of small steel bars arranged ladder-like on a horizontal frame, and struck by means of little hammers. The one most usually employed has a compass of two octaves sounding sometimes one, sometimes two octaves higher than written. Three octave instruments are in existence but are less frequently played. A small keyboard is sometimes employed similar to the piano keyboard. The principal function of this little instrument in the symphony orchestra is, according to Forsyth, to "brighten the edges" of a figure or melody heard in the upper register. It is frequently combined with a piccolo or an E flat clarinet for this purpose, and in such cases is audible above the din of an orchestra playing forte. The glockenspiel has been used by Wagner inWalküre, Siegfried and Die Meistersinger. Meyerbeer, Delibes, Massenet and many other moderns have used it also.