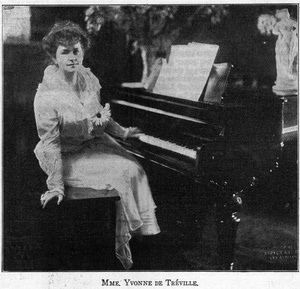

By YVONNE de TREVILLE

Though born in Texas, Mme. Yvonne de Treville may be regarded as an international singer, since she is as well known in Europe as here. She enjoyed very excellent training as a coloratura soprano, and has appeared in opera at the Opera Comique, Paris; Opéra Imperial, Petrograd; Théatre de la Monnaie, Brussels, and at the Imperial Opera in Vienna. She has an extended operatic repertoire, but has latterly been devoting herself more especially to concert work. Her costume recitals have been a very successful feature of this work, especially that in which she appears as “Jenny Lind”, singing some of the songs that the famous prima-donna sang when she so wonderfully charmed the generation before us.

Coloratura singing is that in which trills, roulades, staccato and other embellishments are the principal feature. With the possible exception of the case of Adelina Patti, the acquiring of the necessary flexibility for correct coloratura singing has always entailed long, hard and continuous work. The question, therefore, of when one should begin to train a soprano voice of that sort is one of great importance, and there is grave danger in beginning too young. Under a careful, watchful teacher vocal studies can be started at thirteen or fourteen years, and there are instances of celebrated prima-donna making their professional debuts as early as that.

Coloratura singing is that in which trills, roulades, staccato and other embellishments are the principal feature. With the possible exception of the case of Adelina Patti, the acquiring of the necessary flexibility for correct coloratura singing has always entailed long, hard and continuous work. The question, therefore, of when one should begin to train a soprano voice of that sort is one of great importance, and there is grave danger in beginning too young. Under a careful, watchful teacher vocal studies can be started at thirteen or fourteen years, and there are instances of celebrated prima-donna making their professional debuts as early as that.

Great care should be taken not to strain or tire the vocal organs, and much depends on the general health. If such training is postponed till seventeen or eighteen, preliminary studies of the violin and piano should be begun as early as possible, and, the study of foreign languages mastered early in life will prove invaluable the student later on.

In practicing scales, trills, staccato, etc., it is not sufficient merely to sing the notes mechanically. The student should form a mental picture of beauty of tone and pitch before emitting a sound. It is for this reason that the violin is an admirable instrument for future vocalists to study in early childhood. Christine Nilsson, Marcella Sembrich and the writer of this article are among many coloratura prima-donnas who have played the violin first. Madame Sembrich has said in regard to her wonderful cantilena, “My violin playing helped me to acquire it. The bow is the breath of the violin.” In coloratura singing, as in dramatic or declamatory singing, the foundation of tone-production is breath-control, and it is impossible to impress this point too strongly upon the student.

We will see in the article on Jenny Lind how the great singing teacher, Manuel Garcia, who died in 1906 at the age of one hundred and two years, after having invented the Laryngoscope, who trained not only Jenny Lind, but Antoinette Sterling, Charles Santley, Mathilde Marchesi, Julius Stockhausen and others, famous as teachers of Eames, Melba, Calvé, Henschel, Van Rooy, etc., insisted most strongly on deep controlled breathing. He considered exercises of scales, trills, arpeggios, chromatics and similar technical work indispensable to good singing. These exercises are all the more indispensable to good coloratura singing.

One hour a day of such exercises, divided into periods of from ten to fifteen minutes each, combined with mental work and concentration of thought during that hour, will bring sure and satisfactory results, if the breath is deep and controlled. Breath-control goes hand-in-hand with the acquisition of vocal pace and agility, but breath-control can also be practiced apart. I would advise any singer to begin the day by going through a series of from five to ten exercises in deep breathing before getting up in the morning. Repeat the same exercises on retiring at night, and the results will be very beneficial.

The scales, simple and chromatic, as well as the trill, should be practiced very slowly at first. The trill should be practiced in three different tempi to make it even and distinct.

The day when a pupil was willing to study eight years before singing a song is over, but at least two years are necessary to acquire agility and technical control for coloratura singing. The third year should be devoted to acquiring the repertoire.

It is difficult for us to realize that the old dramatic coloratura soprano sang the airs of Mozart’s Seraglio, Rossini’s Semiramide and even Weber’s Euryanthe with full voice, and only moderately fast. Also that contraltos, baritones and tenors were trained for coloratura singing. Rubini, the “golden voiced tenor,” born in 1795, became famous for his trill.

Such arias as those of Handel’s and Mozart’s operas are admirable for the student of coloratura style, and they should be studied mentally before a sound comes from the throat of the singer. In this way the florid music will take on the emotional color so precious in its interpretation.

After the singer has mastered these arias, those of Rossini, Bellini, Douizetti (sic), etc., will come comparatively easy, and the technical difficulties offered by Una voce poco fa, Ah, non giunge, Perche non ha, or even Meyerbeer’s Mad Scene from the Camp of Silesia written, as it was, to test the superlative skill of Jenny Lind, will be reduced to the class of “vocalizzi,” but to which this method of mental, preliminary study will give unusual dramatic value.

The student should bear in mind that the mere overcoming of technical difficulties is not sufficient. When a singer is announced as a coloratura-soprano the public has a right to demand that her singing shall be “colored” as the name implies, and colored by the emotional meaning of the words of the aria or song. Even a trill can be made to express many different feelings. My observations of bird song, in California this summer, have proved to me how varied it can be even when considered from the technical standpoint. Fluent execution and flawless technique are indispensable to a coloratura soprano, but these are only means to an end, the end being artistic interpretation in coloratura style.

Richard Wagner, whose music is commonly supposed to demand just the opposite of agility, was a strong advocate of the mastery of coloratura, and he strongly advised the singers to perfect themselves in this style. The Brünhilde who attempts the “Hojotoho,” or the Forest Bird who tries to sing the measures allotted her in Siegfried, without a preliminary training in bel canto, of which agility is an essential part, will feel its lack, for bel canto is the foundation of the singing of to-day as well as of all times.