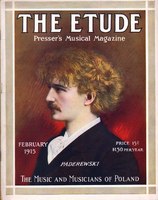

THE BEAUTY OF POLAND’S NATIONAL MUSIC.

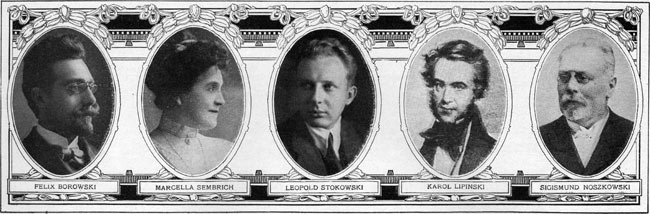

BY MME. MARCELLA SEMBRICH

The Renowned Prima Donna.

[The Etude invited Mme. Sembrich to contribute to this issue, because of all the Polish singers who have come to America none has a warmer place in the hearts of the American people than this great artist. Mme. Sembrich whose real name is Praxede Marcelline Kochanska (Sembrich was her mother’s name) was born at Wisniewczyk, Galicia (Austrian Poland). She studied violin and piano at the Lemberg Conservatory with Prof. Stengel, who later became her husband. Afterwards she studied with Epstein in Vienna. She then found that her future lay in her voice and studied with Rokitansky and Lamperti. For thirty years she has been one of the foremost singers of the world. Her charming soprano voice and her exquisite skill in using it have never been excelled by any singer. Mme. Sembrich is the president of the American Polish Relief Society. Her article is filled with the fine, high- minded spirit of her country. —Editor’s Note.]

We Poles are an old people, although modern civilization has not given us much consideration in this regard, but insists on associating us more with political trouble than with culture. What can we do—thrown about as we have been by the Great Powers of Europe, who have no consideration for the ties of Race? But we are proud of the part we have played in the civilization of the past and hopeful of our future.

Of course we do not know what the awful war, now going on, will result in for the Polish people, but every true Pole, whether he was born and raised under German, Austrian or Russian domination, keeps alive his love for his fatherland and its pride in its literary and musical glories. We are proud of what we have done in music. We have kept alive our love for our old hymns and our old folksong and perhaps even our enemies, whether arrayed on the one side or the other, just now, will forgive us some of our pride, when they think how they, like all the world, have profited by some of the things which the Poles have given them.

Just now, when everybody is dancing to the rhythms which Africans introduced into America, it might be worth while to recall how much artistic music owes to the Polish dances which have made their way into modern concert and opera music. Think of what the Mazurka, Polonaise and Krakowiak have meant to the cultured music of the last century; and their forms and spirit have come out of the songs which the simple people of my country sing now and have for hundreds of years.

Then also, because all the world is waking up to the beauty of national songs, it is to be hoped that more attention will soon be given to Polish composers.

We Poles have not had much to think about that makes us happy, except those things that our people did long ago when we were a nation; recognized as a nation or striving to maintain ourselves as a nation. When Liszt tried to tell what Polish music was like, he used the word źal, meaning pain and sorrow and such mournful things. If Polish songs, whether they be true folksongs or songs written in the manner of the folksongs, reflect those feelings, it is because of Poland’s political history, for by nature, the Poles are a proud and chivalrous people.

We tell you that, in the rhythms of our dances, which rhythms also color all of our folksongs, not all is sorrowful. When our dancers leap into the air and click their heels together, they are not thinking of their troubles, nor trying to forget them altogether, like their Russian kinsmen, but showing the old joy of the Slavic people when they were great in the eyes of the world, as they still are in their own.

From this you will realize that I am hoping that soon the world will awaken to the realization of our Polish composers, Sowinski, Wielkowski, Zarzycki, Moniuszko and the rest. I need not tell about Chopin, for all the world knows about him, though, perhaps, only a Pole can feel all that his music has to say. I might add a word in the same spirit about my friend Paderewski, who is an eloquent Polish musical poet, as everybody knows who has studied or heard his songs and instrumental pieces.

CHOPIN - POLAND’S NATIONAL POET

BY LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI

Conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

[Mr. Leopold Stokowski’s grandfather was forced to leave Poland because of his part in the fight to gain freedom for Poland. Mr. Stokowski’s father married an Irish lady and the conductor himself was born in London somewhat over thirty years ago. After graduation from Oxford University he spent many years on the continent making his home in Germany. As a musician he was decidedly precocious, playing the piano, violin, organ, viola and tuba. At the Royal College of Organists in London he took highest honors and was shortly thereafter appointed organist of St. James in Piccadilly. His studies in composition were conducted under Parry and Stanford. Ten years ago he came to America as organist of St. Bartholomew’s Church, one of the finest positions of its kind in America. After leaving St. Bartholomew’s he toured Europe as a guest conductor and was then selected as the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, serving for over one year. His next appointment was as conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in which position he has been immensely successful. The orchestra is now ranked as one of the finest in the world. In 1911 Mr. Stokowski married the well-known pianist Olga Samaroff. When invited to participate in this issue he selected Chopin as his subject claiming that the average musician and even the average Chopin enthusiast was not unlikely to fail in giving Chopin his rightful place because the great Polish composer confined himself largely to one instrument. Chopin’s position in musical art is not to be measured by the medium he chose for expression. The close student will find in Chopin a creative genius in whose works new wonders occur on almost every page.

Nations, like men, contrast vividly with each other through their opposing characteristics. Although politically grouped under the same government, how different is the national life and art products of Bohemia and Hungary, or of Prussia and Bavaria, or of England and Ireland.—Editor’s Note.]

Probably no country in all history has been more torn and crushed in the political grinding together of powerful and warring neighbors than Poland. And yet how clear-cut and sharp-edged is her national character. Formerly, in Poland’s flowering time, the more powerful aristocrats, each surrounded by a group of lesser nobles, who formed at once their army and their court, lived a life of martial activity, but were at the same time lovers and patrons of literature and the arts. Their life formed the soil out of which the national character grew—impulsive, generous, noble, careless, imaginative.

Later the pressure of the great political forces surrounding Poland became too great. Although politically subjugated, her spirit remained defiant and yearned always for freedom, as the unexampled series of revolutions in Poland testify. No sacrifice of self was too great for freedom and the Patria, and the fires of political hatred, war, self-sacrifice, failure, burnt their deep brand into the national character adding new qualities of intensity of emotion, melancholy, brooding.

How are national ideals and characteristics nourished and kept alive from generation to generation in a community? And how are they best portrayed to other nations and periods? Mainly through the national literature. Poland has an unusually rich literature, which had reached maturity when the Russian and German literatures were still in their infancy. Unfortunately, with the exception of a few unsatisfactory translations, this immense literature is lost to all the outside nations. The spirit, beauty, and fiery chivalry of Poland’s poetry would be forever non-existent to millions were it not that one of Poland’s greatest lyric poets wrote in a universal language—music.

Chopin has expressed the pure essence of the Polish national character. The combining in one person or art-work of the violently contrasting hauteur and chivalry of the aristocrat with the careless impulsiveness of the artist is essentially Polish. Another national trait is the sudden transition from the most naive and joyous gaiety to a brooding melancholy, which is almost painful in its intense and emotional longing for an ideal which seems unattainable. Again, who ever expressed with such overwhelmingly power the frenzy of protest which leads to revolution as Chopin has done in the Prelude in D moll, Opus 28? Sometimes in playing or listening to a Mazurka or Valse of Chopin one seems to see through a mist directly into a Polish salon of the old times. One feels the warmth and spontaneous gaiety, one sees the bright lights and the aristocratic bearing of the dancers—so strong is the imaginative impression made by this unrivaled poet.