The Romance of the Chopin Preludes

By MRS. BURTON CHANCE

With Fanciful Illustrations by the Noted German Impressionist, Robert Spies

There are probably no more popular pieces of piano-music in the world than Frederic Chopin’s Préludes. One cannot be too great to play them, neither can one be too small, for some are simple enough to be given even to the stumbling fingers of a little child. But really to play them one should first know how they were composed. The whole thing is a fairy tale— almost unbelievable, and yet here are the Préludes, a quite substantial outcome of a story seemingly as gold and blue and insubstantial as a dream.

There are probably no more popular pieces of piano-music in the world than Frederic Chopin’s Préludes. One cannot be too great to play them, neither can one be too small, for some are simple enough to be given even to the stumbling fingers of a little child. But really to play them one should first know how they were composed. The whole thing is a fairy tale— almost unbelievable, and yet here are the Préludes, a quite substantial outcome of a story seemingly as gold and blue and insubstantial as a dream.

About 1830 the young Chopin fled from Warsaw to Paris to escape from melancholy and Marie Wodzinska. Marie Wodzinska had refused his love. Her answer had been, “I will never oppose the will of my parents,” and Chopin, only a strolling pianoforte player had been summarily dismissed. But in Paris it is easy to forget. “Me voilá lancé,” he writes, and one can easily imagine the rest.

On the way to the salon of a popular Parisian Countess, one evening, Chopin imagined, as he mounted the marble staircase, that he was being followed by a strange magnetic influence, a shadow that exhaled the odor of violets! He felt almost like turning back to investigate, but the crowd pushed him forward and he soon found himself within the salon doors, still vaguely puzzled, among a large gathering of the most brilliant and talented people in Paris. Toward the end of the evening when only a few of the Countess’ friends were left, Chopin was asked to play. He sat down at the piano and soon lost himself in one of his famous improvisations. Suddenly he looked up and began to blush furiously, for, sitting on the end of the piano, leaning breathlessly toward him was a wonderful creature exhaling the well-remembered odor of violets, whose dark passionate eyes were bent upon him with such intimate scrutiny that he faltered in his playing and soon made some excuse to stop. One version of the story is that George Sand (for it was she) kissed the young Chopin then and there on the lips, and so sealed to herself forever the beautiful soul she envied, and from that moment so ardently loved.

George Sand, already famous as a writer and the heroine of several love affairs, was, when she met Chopin, one of the most brilliant, magnetic and stirring personalities in all Europe. Her influence could not have been other than absolute over a tender, sensitive, only half-fulfilled soul such as that of Frederic Chopin. How soon must the pale image of frightened Marie Wodzinska have fled from his mind, and how utterly, even how eagerly, must he not have poured himself out into the seductive mould held for him in the beautiful hands of Aurora Dudevant! He became what she desired, he did unquestionably what she deemed best—a strange picture is it not?—a lawless, passionate, creative woman leading almost as a child is led, the delicate youth whose genius and physical weakness made so powerful an appeal to all that was best within herself.

George Sand in later years said to Dumas that her love for Chopin was all maternal and protective. Be this as it may, George Sand at 34 was at the very pinnacle of her development both as a writer and as a woman; it would have been strange, indeed, had not Chopin, though but 28, found her fascinations quite overwhelming. One of Chopin’s earliest biographers relates that though George Sand’s face was stern, masculine and even repellant, her love for Chopin so changed and softened her features that he forgot what was unfeminine in her and returned her affection with the greatest ardor and devotion.

The Préludes were the outcome of this love. Chopin was threatened with very serious lung trouble, and in order that he might spend the winter in a better climate, George Sand carried him off to the Balaric Isles, for “he needed love, and he also needed rest and sunshine, to be waited upon and worshiped while he basked in one of the back-waters of life.”

The Préludes were the outcome of this love. Chopin was threatened with very serious lung trouble, and in order that he might spend the winter in a better climate, George Sand carried him off to the Balaric Isles, for “he needed love, and he also needed rest and sunshine, to be waited upon and worshiped while he basked in one of the back-waters of life.”

Why the Balaric Isles, one cannot help asking, with Europe full then as now of interesting and luxurious winter cities? Surely it could not have been a regard for the conventions, one would hardly look for this from George Sand! Yet it probably was in order to evade observation that the lovers chose Majorca, for we find the sensitive Chopin begging his friends to keep his secret, seemingly oblivious to the fact that George Sand in her voluminous and brilliant letters to people all over the world was revealing it right and left!

Of his first impressions of Palma, Chopin writes: “Here I am in the midst of palms and cedar and cactuses and olives and oranges and lemons and aloes and figs and pomegranates. The sky is a turquoise blue, the sea is azure, the mountains are emerald green; the air is pure like the air of Paradise. All day long the sun shines and it is warm, and everybody walks about in summer clothes. At night one hears Guitars and Serenades. Vines are festooned on immense balconies; Moorish walls rise all around us; the town like everything else speaks of Africa. In a word it is an enchanted life that we are living——-“

This enchanted life might have gone on indefinitely, but that the winter rains came down and Chopin began to cough. Word was soon passed around the town that he was a consumptive, and the frightened landlord ordered his tenants out as speedily as possible. This was a great shock to George Sand, on whom fell the whole burden of deciding what to do next, but Chopin, still happy and beloved, gives only an amusing account of his illness.

“All the three doctors in the island came to my bedside to consult. One of them said that I should die eventually, another that I was then dying, and the third that I was already dead; and yet in spite of them all I continued to live just as I lived before they were called in.” Nevertheless, his condition was serious, for the Balaric Islands were only just emerging from barbarism, and it was hard to get even the necessities for ordinary decent living, much less those needed for the comfort of an ill and suffering man.

But to the indomitable spirit of George Sand there was no such thing as defeat. She intended that Chopin should have the full benefit of the Southern climate, and so, when forced to leave their little house in Palma, she found for him, far up in the mountains and surrounded by a grove of orange trees and a deserted Carthusian monastery, rejoicing in the romantic name of Waldemosa, which she rented, together with sufficient furniture, for about two hundred dollars from a political refugee, who was glad of the unforeseen opportunity to get rid of his effects. Chopin’s piano was painfully dragged up the mountain side through the pine forests. This piano and the stove which accompanied it caused the authorities of Palma great excitement, for they regarded them as diabolical machines intended to blow up the island! Not only the piano and the stove, but everything else necessary to support life had to be dragged toilfully and expensively up the mountain to Waldemosa!

But love and genius alone together on a hill-top with only each other and Nature’s most wonderful pageant to contemplate are not likely to be discouraged by practical difficulties. They are also likely to be entirely satisfied with their workshop. In the Carthusian monastery of Waldemosa genius burned and love held the candle. Chopin composed and George Sand began her novel Spirideon. They are like children, these two, enthusiastic and full of happiness. “In the month of December,” writes George Sand poetically, “and in spite of the recent rains, the torrent was only a charming brook babbling among the grass and flowers. The mountain smiled on us and the valley opened at our feet like a valley in spring.” And again, in a letter to a distant friend, she says, “When Chopin was in a desponding mood the piercing cry of the hungry eagle among the crags of Majorca, the mournful wailing of the storm and the stern immoveability of the snow-clad heights would awaken gloomy fancies in his soul. Then, again, the perfume of the orange blossoms, the vine bending to the earth beneath its rich burden, the peasant singing his Moorish songs in the field would fill him with delight.”

But love and genius alone together on a hill-top with only each other and Nature’s most wonderful pageant to contemplate are not likely to be discouraged by practical difficulties. They are also likely to be entirely satisfied with their workshop. In the Carthusian monastery of Waldemosa genius burned and love held the candle. Chopin composed and George Sand began her novel Spirideon. They are like children, these two, enthusiastic and full of happiness. “In the month of December,” writes George Sand poetically, “and in spite of the recent rains, the torrent was only a charming brook babbling among the grass and flowers. The mountain smiled on us and the valley opened at our feet like a valley in spring.” And again, in a letter to a distant friend, she says, “When Chopin was in a desponding mood the piercing cry of the hungry eagle among the crags of Majorca, the mournful wailing of the storm and the stern immoveability of the snow-clad heights would awaken gloomy fancies in his soul. Then, again, the perfume of the orange blossoms, the vine bending to the earth beneath its rich burden, the peasant singing his Moorish songs in the field would fill him with delight.”

We find Chopin himself no less enthusiastic and happy. In one of his earliest letters to Paris, he writes, “Lost between the rocks and the sea in an immense deserted convent of the Carthusians, confined in a cell the one door of which is rather larger than the gates of Paris, you may picture your Frederic, with his hair all out of curl, deprived of his white gloves, and as pale as ever. My cell is about as large as a coffin, a vault thick with dust serving as a lid. The windows are small and underneath these windows grow orange trees, palms and cypresses. Opposite to them, underneath a rose window in the Arabian style is my bed. Close to the bed is a small table, and on this table, a great luxury, stands a metal candlestick holding a miserable candle, the works of Bach, and my own compositions in manuscript, that is the full history of my belongings. And what a silence! One may shout at the top of one’s voice and no one will hear. Truly Nature is beautiful!—”

It was here, then, amid such surroundings as these, that the famous Préludes were written. These noble themes so often blindly played by unwilling pupils in stuffy provincial parlors, came into being under the blue sky of the Mediterranean to the tune of the wild eagle’s scream, and the scent of the warm orange blossom upon the silent, budding earth. They are the captured notes of the wild bird, Love, singing to its mate, and they were conceived and uttered in an atmosphere seldom indeed vouchsafed to those who struggle with creative work.

HOW THE PRÉLUDES WERE WRITTEN.

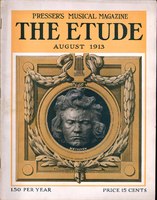

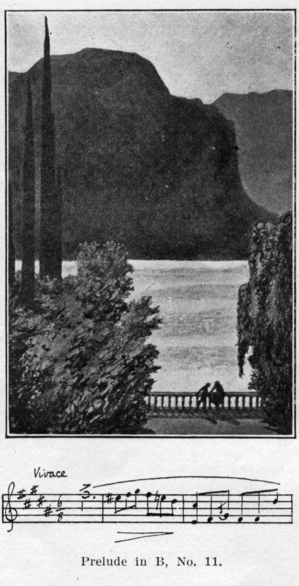

George Sand speaks of the Préludes in the Histoire de Ma Vie. She writes, “While staying here, Chopin composed some short but very beautiful pieces which he modestly entitled Préludes. They were real masterpieces. Some of them create such vivid impressions that the shades of the dead monks seem to rise and pass before the hearer in solemn and gloomy funereal pump (the middle movement, for example, No. 15 in D flat major). Others are full of charm and melancholy glowing with the sparkling fire of enthusiasm, breathing with the hope of restored health. The laughter of children at play, the distant strains of the guitar, the twitter of the birds, in the damp branches, or the sight of the little pale roses in our cloister garden, pushing their heads up through the snow, would call forth from his soul melodies of indescribable sweetness and grace. But many also are so full of gloom and sadness that, in spite of the pleasure they afford, the listener is filled with pain. I apply this particularly to a Prélude (No. 6, B minor) he wrote one evening which thrills one almost to despair.”

George Sand goes on in her letter to describe at length how she went down to Palma to make some necessary purchases one day and was caught in a heavy storm not reaching the monastery until midnight, having really been exposed to great danger from the swelling torrents and an unruly driver, who finally deserted her, leaving her to climb the mountain alone in the storm. She found Chopin, his anxiety so great “that it had been, as it were, transformed into a kind of tranquil despair; he was playing his noble and beautiful Prelude, weeping as he played. He rose, uttering a loud cry and said in a strange, hollow voice, ‘Ah, I thought you were dead’—he had sunk into a kind of stupor (he afterwards explained) and fancied while he was playing that he had been removed from earth and was no longer in the land of the living. He imagined that he was drowned, and as he lay at the bottom of the sea could feel the cold drops keeping time as they dropped upon his breast—the Prélude he wrote that evening recalls indeed the raindrops falling on the roof of the cloister, but according to his conception these drops are tears falling from Heaven on his heart.”

As the day passed by and the idyll spun itself out, Chopin relaxed more and more contentedly in the atmosphere of sympathy and comfort with which George Sand so lovingly enveloped him.

He did not ask questions but accepted as a matter of course the efforts made by his heroic companion to render his path smooth. She was anxious, worried, overworked but never weary of standing between him and the world, and of making everything pleasant that he might do his immortal work untroubled. Often when servants rebelled or ran away from the loneliness of their cloistered retreat, she had to sweep and cook, and her difficulties in obtaining food, even food necessary to life, made every day a supreme test of ingenuity and generalship. Chopin never knew this. Nor is it likely that he ever began to realize all that George Sand did for him that honeymoon winter in Majorca. Often indeed she had to get up in the middle of the night, and sit at their one little table, her feet perishing with the cold from the rough stone pavement of the “cell” making “copy” for Buloz by the light of one poor draught-ridden candle. “Copy” for Buloz meant money, money meant comfort for Chopin, and so the busy pen flew onward hour after hour. Needless to say, she got her reward. It must have been no little joy to sit by of a moonlit evening and look over the pines to the Mediterranean while Chopin composed—all for one’s own benefit, and oneself beloved! The reward was great. Oh! but the price was great, too.

He did not ask questions but accepted as a matter of course the efforts made by his heroic companion to render his path smooth. She was anxious, worried, overworked but never weary of standing between him and the world, and of making everything pleasant that he might do his immortal work untroubled. Often when servants rebelled or ran away from the loneliness of their cloistered retreat, she had to sweep and cook, and her difficulties in obtaining food, even food necessary to life, made every day a supreme test of ingenuity and generalship. Chopin never knew this. Nor is it likely that he ever began to realize all that George Sand did for him that honeymoon winter in Majorca. Often indeed she had to get up in the middle of the night, and sit at their one little table, her feet perishing with the cold from the rough stone pavement of the “cell” making “copy” for Buloz by the light of one poor draught-ridden candle. “Copy” for Buloz meant money, money meant comfort for Chopin, and so the busy pen flew onward hour after hour. Needless to say, she got her reward. It must have been no little joy to sit by of a moonlit evening and look over the pines to the Mediterranean while Chopin composed—all for one’s own benefit, and oneself beloved! The reward was great. Oh! but the price was great, too.

So this is the story of how the famous Chopin Préludes came into being. When next we hear or play them do not let us forget to say a little prayer for the valiant soul of Aurora Dudevant.

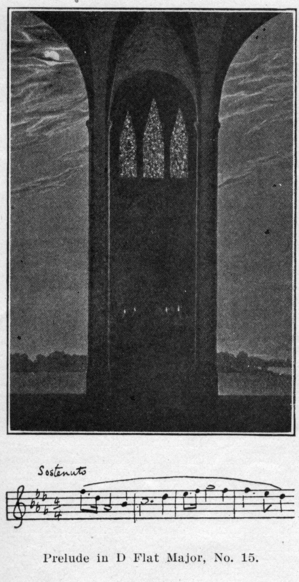

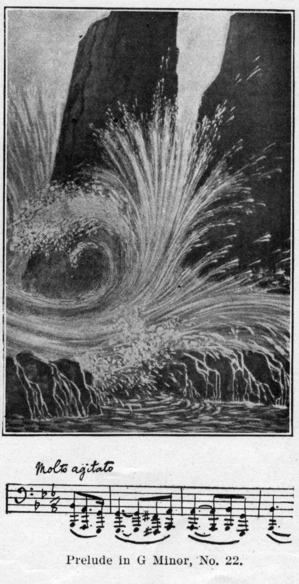

[Editor’s Note.— It is the fate of music that survives in popular favor to receive fanciful names and mysterious legendary biographies. We all know the apocryphal nature of the Beethoven Moonlight Sonata legend, yet it seems a trifling task to rob so beautiful a piece of so appropriate a story. Just who is responsible for the christening of the vast number of picturesque titles never imagined by the composers is hard to tell. In the present case, we find that Mr. James Huneker in his Chopin, The Man and His Music brings forward quite abundant proof to show that Chopin wrote most of the preludes before he went to the Balaric Islands and that his task there was one of refining and completing his sketches. The sketches which head this article are from drawings by Robert Spies, which have been attracting wide attention in Germany. They are pictorial representations of some of the legends which have attached themselves to the Chopin Preludes. Of the Prelude number four, Niecks, a distinguished writer upon Chopin, says, “a little poem, the exquisitely sweet, languid pensiveness of which defies description. The composer seems to be absorbed in the narrow sphere of his ego, from which the wide noisy world is for the time shut out.” The eleventh prelude in B minor is so short that it is ignored by some. Just how the artist would have this apply to his picture is hard to tell. The Prelude number fifteen in D flat is possibly the best known of all of the preludes. Of this Kleczynski, Chopin’s biographer has said, “The foundation of the picture is the drops of rain falling at regular intervals.” George Sand, it will be remembered, mentioned these in connection with the Chopin Prelude in B minor (No. 6) “Chopin saw himself drowned in a lake; heavy ice cold drops of water fell at regular intervals upon his breast; and when I called his attention to these drops of water, which were actually falling upon the roof, he denied having heard them.” This prelude has come to be known as the Rain Drop Prelude. Mr. Huneker says of the Fifteenth Prelude, “The work needs no program. Its serene beginning, lugubrious interlude, with the dominant pedal never ceasing, a basso ostinato, gives color to Klecyzynski’s contention that the prelude in B minor is a mere sketch of the idea elaborated in Number fifteen. The Prelude number twenty-two is one of the most vigorous of all the preludes. Its rapid rumbling octaves in the left hand are surmounted chords in the right hand which were considered extremely iconoclastic in their day. The prelude is rushing, impetuous and highly dramatic. That the artist has chosen a torrent to represent this Prelude seems most appropriate.”]