The Germany of to-day is a strong federation of German states under the imperial dominion of the Kaiser. One hundred years ago Germany was no more or less than that section of Europe tenanted by people of the German race, divided into small kingdoms and principalities, of which Austria was always considered a part. It had suffered from the terrific blows that Napoleon delivered to his enemies and was staggering along under the influence of the reactionary Austrian minister Metternich, who was so suspicious that he even prevented musical festivals with the fear that they might be revolutionary gatherings. The political renaissance of Germany really began with the entrance of that master of diplomacy, Otto von Bismarck. When Brahms was born Bismarck was at the beginning of his iron career. Under the great Chancellor, Prussia became the force which resulted in the German Empire in 1871. All these things occurred during the life of Brahms, and it is not difficult to believe that much of the great power which marks his works came from the dynamic political atmosphere of his time, an atmosphere also capable of influencing a totally different type of composer such as Brahms’ great contemporary, Richard Wagner.

BRAHMS’ ANCESTRY.

Brahms’ family name appears in some forms as Brahmst. At least it may be so found upon the program of a concert given in 1849. The master’s father was an able but little known musician, Johann Brahms. He played the viola, violin, ‘cello, flute, horn and contra-bass. Here and there he managed to pick up an odd job in addition to his regular work as a performer on the double bass at the theatre and in the Philharmonic concerts, and as a member of the town military band. Despite his versatility and ability, Brahms’ father was so poor that he was not above “passing the hat” when he played in summer gardens. Brahms’ mother was delicate, ordinary, and it is said walked with a conspicuous limp. She was seventeen years older than her husband. History records little of her other than that she was affectionate, blue-eyed, pious and entitled to that greatest German distinction of feminine virtue, tuchtige hausefrau (tidy housewife).

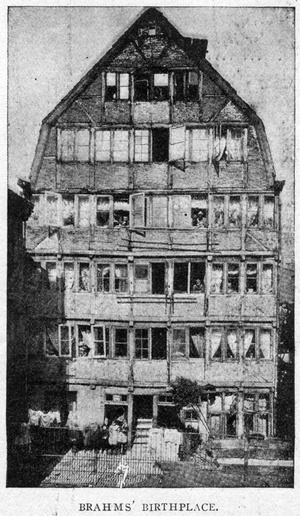

BRAHMS’ BIRTHPLACE.

As you look upon the ramshackle building in which Brahms was born, it should be remembered that, like so many other German edifices of the kind, it was a Wohnung or a tenement. The Brahms family occupied only a few rooms, and their home was very close indeed to abject poverty. This “home” was located on a dismal little lane in the city of Hamburg. Brahms was born there Tuesday, May 7th, 1883. His mother was then forty-four years old. His father twenty-seven.

Brahms’ first teacher was a pianist named Cossel, who gave the boy his first lessons when he was seven years old. At ten he was so advanced that he played a study by Herz at a Charity concert. During the same year his self-sacrificing teacher, realizing what splendid talent the boy had, took him to the nearby city of Altona to Marxsen, who had been Cossel’s own teacher in the past. Brahms played for the old master and was assured that he had better continue under Cossel. However, his father’s friends were not satisfied and a concert was given in the Bier Halle “Zum Alt en Rabe,” the proceeds of which were to be applied to the education of the young musician. With the requisite funds in hand Marxsen was approached again and consented to accept the boy as a pupil for one lesson a week, but stipulating that he should also take two lessons a week from Marxsen’s former pupil Cossel. Finally Marxsen took the boy under his care, teaching him without compensation. The world owes a great debt to Cossel since it was only through his magnificent self-sacrifice that this was brought about, and through his persistence that the parents of the boy were prevented from sending him upon a tour as a prodigy, which might have proved ruinous.

Marxsen was a thorough musician who had had an excellent training in Vienna. He took an unusual interest in the boy and saw to it that his general education in the regular school work was not neglected. He obliged him to transpose long pieces of music at sight.

At the age of fourteen Brahms gave his first concert, playing the following program :

Adagio and Rondo - Rosenhain

Fantasie on William Tell - Dohler

Serenade for left hand - Marxsen

Etude - Herz

Fugue - J. S. Bach

Variations on a Volkslied - Johannes Brahms

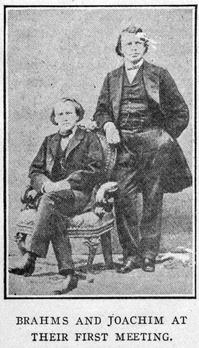

In 1853 Brahms went upon a tour with the Hungarian violinist, Eduard Remenyi, a great relief from his previous years of musical hackdom, teaching at the rate of twenty-five cents a lesson and playing in lokals (cafes). Remenyi introduced Brahms to Joachim, who recognized his great talent. Joachim in turn introduced the young composer to Liszt and to Schumann. Schumann was immensely impressed with his works and wrote an article lauding Brahms in the “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik,” entitled Neue Bahnen (New Roads). During the four years, 1854-1858, Brahms was Court Music Director for the Prince Lippe-Detmold. In 1862 Brahms went to Vienna to be near his friend, Theodor Kirchner. In the Austrian musical capital he was honored with the post of Director of the Sing Akademie, and later with that conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. From 1864 to 1869 he spent part of his time in Hamburg, Zurich, Baden-Baden and other cities, but Vienna became his ultimate home. He made numerous tours as a pianist, but his playing was for the most part too serious in character to win him the great enthusiasm that the virtuoso expects from the public. His life was marked by his natural distaste for notoriety and the turmoil of the world. He ignored the degree of Doctor of Music when it was offered to him by Cambridge University (1877), but accepted that of Ph.D from Breslau University (1881.) In 1886 he was Knighted by Prussia (Order of Merit). He was the polar antithesis of Richard Wagner, to whom tranquility was a welcome but an unattainable attribute. The difference between Brahms and Wagner was the difference between the silent majesty of peace and the glorious clamor of war. Yet Wagner unquestionably placed himself and his music in more definite contact with the human needs of his time than did the ascetic Brahms, working in art principles often far to (sic) complicated for those of more frail intellects to comprehend.

In 1853 Brahms went upon a tour with the Hungarian violinist, Eduard Remenyi, a great relief from his previous years of musical hackdom, teaching at the rate of twenty-five cents a lesson and playing in lokals (cafes). Remenyi introduced Brahms to Joachim, who recognized his great talent. Joachim in turn introduced the young composer to Liszt and to Schumann. Schumann was immensely impressed with his works and wrote an article lauding Brahms in the “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik,” entitled Neue Bahnen (New Roads). During the four years, 1854-1858, Brahms was Court Music Director for the Prince Lippe-Detmold. In 1862 Brahms went to Vienna to be near his friend, Theodor Kirchner. In the Austrian musical capital he was honored with the post of Director of the Sing Akademie, and later with that conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. From 1864 to 1869 he spent part of his time in Hamburg, Zurich, Baden-Baden and other cities, but Vienna became his ultimate home. He made numerous tours as a pianist, but his playing was for the most part too serious in character to win him the great enthusiasm that the virtuoso expects from the public. His life was marked by his natural distaste for notoriety and the turmoil of the world. He ignored the degree of Doctor of Music when it was offered to him by Cambridge University (1877), but accepted that of Ph.D from Breslau University (1881.) In 1886 he was Knighted by Prussia (Order of Merit). He was the polar antithesis of Richard Wagner, to whom tranquility was a welcome but an unattainable attribute. The difference between Brahms and Wagner was the difference between the silent majesty of peace and the glorious clamor of war. Yet Wagner unquestionably placed himself and his music in more definite contact with the human needs of his time than did the ascetic Brahms, working in art principles often far to (sic) complicated for those of more frail intellects to comprehend.

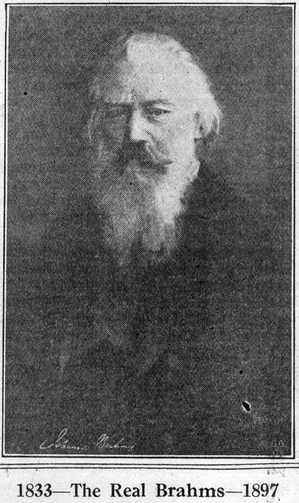

BRAHMS’ PERSONALITY AND APPEARANCE.

Brahms’ appearance was impressive despite the fact that his head was abnormally large and his body small and stocky. His complexion was ruddy, his eyes blue and penetrating, and his hair slightly gray in his advanced years. The fact that his name appeared on several church registers and that similar names of other branches of the same family have been found in records of different churches apparently contradicts the assertion that he was of Jewish ancestry.

Brahms was inordinately fond of walking, particularly walking in the country, after the manner of Beethoven. He rarely missed a day without a stroll of some length. Mountain climbing was another of his favorite pastimes. As he grow more fleshy in his later years he found climbing difficult and would often stop his friend to see some remarkable view when he was really “out of breath” and unable to go further. He was so fond of the open air that he always made it a point to dine in the garden when the weather permitted.

Brahms was somewhat careless in his dress, and for this reason avoided any form of society where he might be obliged to abandon his free attire, often accented by a picturesque loose flannel shirt without a tie of any kind and a broad brimmed soft hat, which he wore in his hand rather than upon his head. Indeed, he is said to have avoided a trip to England to accept the proffered degree of Doctor of Music from Cambridge University, because he feared he would be obliged to wear a dress suit. Indeed, he was one of the most striking figures of the Vienna of his day. He would often appear with a somewhat dingy, brownish-gray shawl thrown over his shoulders and clasped in front with an ordinary pin. Brahms was naturally retiring and was fond of quoting Goethe’s line, “Blessed is he who without hate, shuts himself from the world.”

Although Brahms avoided notoriety he had many friends and enjoyed a controversy above all things. In his youth he had a tendency to be brusque and sarcastic, but with later years this irrascability was softened by good humor. Brahms was a man of wide interests. He was keenly alive to the great innovations of the nineteenth century, the telephone, the telegraph and the phonograph. Brahms was kindly to his servants and such a lover of children that he often permitted them to impose upon him. Once he was seen on all fours playing horse for a small boy who, whip in hand, sat astride the master’s back. Yet, like Beethoven, he never married. He disliked ceremony of any kind and escaped it whenever possible.

BRAHMS AS A PIANIST.

A casual examination of Brahms’ pianoforte compositions reveals at once that he employed chords that ofttimes seem so remote from the conventional chord masses utilized by the average composer that the piano student finds new and often very complicated arrangement of the keys, demanding significant extensions of his technic. It was known that Brahms detested the conventional, and even in his simplest compositions sought a characteristic and distinctly different atmosphere. This, perhaps, gives us a better insight to his methods of playing than do the varying accounts of his performances. In any event Brahms could never be called a virtuoso in the sense that we apply the term to Liszt, Rubinstein, Paderewski, or even Chopin. Joachim said of his playing when Brahms was a very young man, “His piano playing was so tender, so full of fancy, so free, so firey, that it held me enthralled.” Clara Schumann, whom Brahms worshipped almost as a foster-mother, was not so deeply impressed. Yet once, when Brahms was playing alone at the Schumann’s, Clara, who was in another room, exclaimed, “Who are those people in there playing duets!”

BRAHMS’ AS A TEACHER OF THE PIANOFORTE.

BRAHMS’ AS A TEACHER OF THE PIANOFORTE.

One of Brahms’ pupils, Florence May, has written the most, comprehensive life of the master. In it she describes his teaching in a manner that no teacher may read without profit.

“Brahms united in himself each and every quality that might be supposed to exist in an ideal teacher of the pianoforte, without having a single modifying drawback. He was strict and absolute; he was gentle and patient and encouraging; he was not only clear, he was light itself; he knew exhaustively, and could teach and did teach, by the shortest possible methods, every detail of technical study; he was unwearied in his efforts to make his pupil grasp the full musical meaning of whatever work might be in hand; he was even punctual.”

”Remembering what Frau Schumann had said of his ability to assist me with my technic, I told him before beginning with my lessons, of my mechanical difficulties, and asked him to help me. He answered, ‘Yes, that must come first,’ and after hearing me play through a study from Clementi’s Gradus ad Parnassum, he immediately set to work to loosen and equalize my fingers. Beginning that very day he gradually put me through an entire course in technical training, showing me how I should best work for the attainment of my end at scales, arpeggi, trills, double notes, and octaves. At first he made me practice during a good part of my lessons, while he sat watching my fingers, telling me what was wrong in my way of moving them, indicating by his own hand a better position for mine, absorbing himself entirely for the time being in the object of helping me.”

“His method of loosening the wrist was, I should say, original. I have at all events, never seen or heard of it excepting from him, but it loosened my wrist in a fortnight and with comparatively little labor on my part. How he laughed one day when I triumphantly showed him that one of my knuckles, which were then rather stiff, had quite gone in, and said to him: ‘You have done that.’”

“He had a great habit of turning a difficult passage round and making me practice it, not as written, but with other accents and in various figures, with the result that when I again tried it as it stood the difficulties had always considerably diminished and often entirely disappeared.”

“He was never irritable, never indifferent, but always helped, stimulated and encouraged. One day. when I lamented to him the deficiencies of my formal mechanical training and my present resultant finger difficulty, ‘It will come out all right,’ he said, ‘it does not come in a week, nor in four weeks.’”

“He was extremely particular about my fingering, making me rely on all my fingers as equally as possible. One day whilst watching my hands as I played him a study from the Gradus, he objected to some of my fingering and asked me to change it. I immediately did so, but said that I had used the one marked by Clementi. He at once said that I must not change it and would not allow me to adopt his own. A good part of each lesson was generally devoted to Bach, to the Well Tempered Clavier or the English Suites; and as my mechanism improved Brahms gradually increased the amount and scope of my work, and gave more and more time to the spirit of the music I studied. His phrasing as he taught it to me, was, it need hardly be said, of the broadest, while he was rigorous in exacting attention to the smallest details. These he sometimes treated as delicate embroidery that filled up and decorated the broad outline of the phrase, with a large sweep of which nothing was ever allowed to interfere. Light and shade were also so managed as to help to bring out its continuity. Be it, however, most emphatically declared that he never theorized on these points; he merely tried his utmost to make me understand and play my pieces as he himself understood and felt them. He would make me repeat over and over again, ten or twelve times if necessary, part of a movement of Bach, till he had satisfied himself that I was beginning to realize his wish for particular effects of tone, or phrasing or feeling. When I could not immediately do what he wanted he would say, ‘But it is so difficult,’ or ‘It will come,’ tell me to do it again until he found his effect was on its way into being and then leave me to complete it.”

“Brahms, recognized no such thing as what is sometimes called ‘neat playing’ of the compositions of Bach, Scarlatti and Mozart. Neatness and equality of finger were imperatively demanded by him and in their utmost nicety and perfection, but as a preparation not as an end. Varying and sensitive expression was to him as the breath of life, necessary to the true interpretation of any work of genius, and he did not hesitate to avail himself of such resources of the modern pianoforte as he felt helped to impart it; no matter in what particular century his composer may have lived, or what may have been the peculiar excellencies or limitations of the instruments of his day.”

“Brahms, recognized no such thing as what is sometimes called ‘neat playing’ of the compositions of Bach, Scarlatti and Mozart. Neatness and equality of finger were imperatively demanded by him and in their utmost nicety and perfection, but as a preparation not as an end. Varying and sensitive expression was to him as the breath of life, necessary to the true interpretation of any work of genius, and he did not hesitate to avail himself of such resources of the modern pianoforte as he felt helped to impart it; no matter in what particular century his composer may have lived, or what may have been the peculiar excellencies or limitations of the instruments of his day.”

“He particularly disliked chords to be spread unless marked so by the composer for the sake of a special effect. ‘No arpeggios,’ he used invariably to say if I unconsciously gave way to the habit, or yielded to the temptation of softening a chord by its means. He made very much of the well-known effect of two notes slurred together, whether in a loud or a soft tone, and I know from his insistence to me on this point that the mark had a special significance in his music.”

BRAHMS’ FRIENDS.

Despite Brahms’ natural modesty and constant endeavors to escape the “lime-light” he had many friends. The best known of these were Remenyi, Joachim, Liszt and Clara Schumann, all of whom are well known. Theodor Bilroth, one of Brahms’ most intimate companions, was an enthusiastic musician and writer who accompanied Brahms on many of his walks and who was favored with an extensive correspondence. J. V. Widmann was another whose friendship Brahms cultivated. Brahms’ great journalistic champion was the renowned Viennese critic, Dr. Eduard Hanslick, whose defence of his friend was as strong as his attacks upon Wagner were bitter. Brahms had a high admiration for Ernest von Wildenbruch, the Austrian playwright, whose works were especially stimulating to him.

THE BRAHMS-WAGNER CONTROVERSY.

It was natural that those who found Wagner’s modern ideas incompatible with their own should seek a champion whom they might put forward as an opponent of Wagner. As a matter of fact, the entire controversy was fought out upon journalistic lines and was never based upon personal animosity. Brahms was a great admirer of Wagner and rarely missed a first performance of his works when given in Vienna. Wagner, however, often acid and impetuous, was not wont to regard any competitor in a class with himself.

BRAHMS’ COMPOSITIONS.

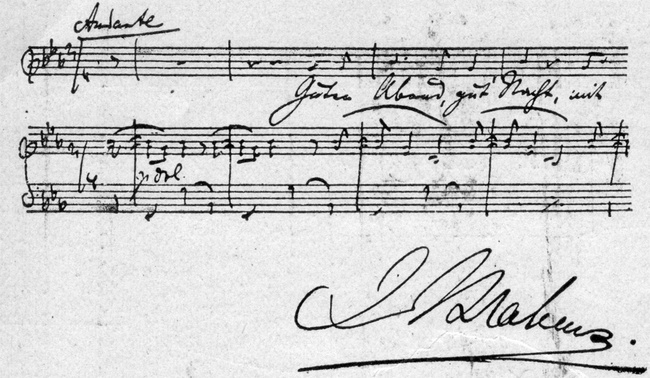

An English writer (Edwin Evans, Sr.) has recently published the first of a series of three large volumes, giving a detailed description of the works of Johannes Brahms. Only by studying a work of this kind can one form a conception of the great number of the collected works of this master. His works have been given opus numbers up to 122. There are some twenty-three works without opus numbers. Many of these opus numbers represent several different compositions in a set. He had a peculiar habit of producing works of a kind in pairs, as two symphonies, two sets of songs, two sets of pianoforte pieces. When his first symphony was produced it made such an impression that it was immediately called “The Tenth Symphony,” implying that it was a worthy successor to the nine Beethoven Symphonies. Brahms wrote four symphonies and four concertos, representing his powerful, reserved, unostentatious style—a style majestic and substantial, but often so lofty that critics of superficial training have described some of Brahms’ compositions as “muddy.” Brahms’ chamber music deserves a chapter in itself since it revives the classical forms in a manner worthy of his greatest predecessors. Ho never wrote any operatic work, but it is believed that he would have done so had he been able to procure a worthy libretto. His Deutsches Requiem places him at once among the great composers of choral works. His songs are particularly beautiful and individual. Among the best are Sapphic Ode, Wie bist du Meine Königen, Magelone-Leider, Botschaft Vier Ernste Gesange, Feldeinsamkeit, In Waldeinsamkeit, Die Mainacht, Von Ewige Liebe, Wiegenlied. Without doubt Brahms’ best known compositions are his Hungarian Dances. These appeared in 1867 as piano duets, and were later arranged for orchestra by the composer. The melodies were for the most part not original with Brahms, and the original edition frankly states that they were “arranged by Brahms,” thus making the frequent accusations of plagiarism unnecessary.

The grandeur which characterizes Brahms’ orchestral works is not absent from his piano pieces. There is, however a peculiar quality about his compositions for the most popular instrument, that have kept them apart from the novice. Many music-lovers seemingly have to develop a taste for them, as one does for rare tropical fruits and scents. In some pieces one has the feeling that Brahms has taken up the art of Schumann as expressed in that master’s Kreisleriana and Fantasia in C and carried it to very lofty altitudes of complexity. Again, as in the second trio of the Scherzo, Opus 4 (Molto Expressivo), one cannot fail to be impressed with the fact that he has imbibed the true spirit of Beethoven as the older master revealed himself in his virile yet emotional slow movements. There is very little of the piano literature of Brahms that is available to the average teacher, precisely as there is little of Browning, Keats or Swinburne that may be employed for pedagogical purposes in the elementary classroom. Brahms’ Intermezzi, Caprices, Ballades, etc., all exhibit his hatred for banality, and for the most part contain special technical difficulties of such a nature that Josef Weiss, a celebrated Brahms’ interpreter, worked for years to arrange a preparatory method for the study of Brahms.

A BRAHMS’ PROGRAM.

Duet, Hungarian Dance, No. 2 - Grade 4

Song, Sapphic Ode - Grade 4

Piano Solo, Valses, Opus 39 (No. 2 and 4) - Grade 4

Song, Wie bist du meine Königin - Grade 5

Chorus, The Little Dustman (Female Voices) - Grade 3

Piano Duet, First Movement C Minor Symphony, No. 1 - Grade 8

Piano Solo, Hungarian Dance, No. 7 (Arranged by Philipp.) - Grade 5

Piano Solo, Andante from the First Sonata (Arranged by Mathews.) - Grade 6

Song, In Waldeinsamkeit - Grade 5

Piano Solo, Cappriccio (Opus 76, No. 2) - Grade 7

Piano Solo, Ballade, Opus 10, No. 1 - Grade 6

Piano Duet, Opus 39 (No. 13 and No. 10) - Grade 4

BOOKS UPON BRAHMS.

Life of Johannes Brahms, by Florence May, two volumes, many illustrations. Brahms by J. Lawrence Erb. Brahms, by Herbert Antcliffe. Johannes Brahms, by Dr. Hermann Dieters. Johannes Brahms, by J. A. Fuller-Maitland. The Works of Johannes Brahms, by Edwin Evans, Sr. (three volumes.)