Personal Reminiscences of the Great Russian Master

By AUBERTINE WOODWARD MOORE

[November is Rubinstein month. The great composer was born on November 28th, eighty-two years ago. Nearly forty years have passed since he visited America. Another generation of young musicians has arisen,—a generation which can form little conception of the sensation which Rubinstein’s great tour caused in America. The following article gives some most interesting ideas of what this important event in our national musical history meant.—Editor of The Etude.]

Toward the middle of the nineteenth century European vocal and instrumental virtuosi began to regard America as a fertile field for the display of their achievements. One of the first celebrated foreign pianists to visit us was Henri Herz, who, fresh from triumphs in Paris, toured the United States, Mexico and South America from 1845 to 1852, dazzling his not over-discriminating audiences rather by the presentation of his own compositions on eight pianos, with sixteen performers, than by his brilliant but frivolous solo work.

Toward the middle of the nineteenth century European vocal and instrumental virtuosi began to regard America as a fertile field for the display of their achievements. One of the first celebrated foreign pianists to visit us was Henri Herz, who, fresh from triumphs in Paris, toured the United States, Mexico and South America from 1845 to 1852, dazzling his not over-discriminating audiences rather by the presentation of his own compositions on eight pianos, with sixteen performers, than by his brilliant but frivolous solo work.

In 1845, too, came Leopold Von Meyer to exercise his blandishments in our principal cities after the most charlatan-like fashion, smiting his keys, when ten fingers were inadequate, with fists, elbows, even nose, and producing music-box, and bell-ringing effects. He performed his antics with lightness and grace, and vastly amused the public, which he, more extravagant than ever, found cold when he returned in 1868.

Signs of improvement in popular taste were already manifest, in 1852, when a Polish gentleman, Wolowski by name, vainly sought to mend his broken fortunes by giving public performances on two pianos at one and the same time. The added announcement that he could execute 400 notes in one measure made scarcely a ripple of excitement, because people were quite sure that no one could count the notes. American concert-goers placed more confidence at that time in Alfred Jaell, who was attracting attention because of his “full, sweet crisp” pianoforte tones. The first American pianist to gain European renown, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, gave his earliest concert in his native land, in New York, during the year 1853. A man of glowing temperament, said by critics to combine the best qualities of Jaell, Herz and Von Meyer, he was, nevertheless, compelled to prostitute his genius to gain the popularity he needed.

THALBERG’S TOUR.

Thalberg, an aristocrat in looks and manner, (he was the natural son of a prince) cold, statuesque, faultless in mechanism, crossed the ocean in 1855, and after touring South America, visited the United States the following year. During the winter of 1856-7 he played in Philadelphia, and “apostle of brilliant emptiness” though he might be, he made a profound impression upon his hearers, especially those who were engaged in attempts at piano-playing. However little he may have advanced the progress of musical art, he at least showed how to gain control of one’s self and one’s instrument, how to sing a melody on the piano, and how to produce smooth, correct and finished passage work. I well remember the long-enduring desire he awakened in my own youthful breast to produce similar pearly scales, rippling arpeggios, and singing melodies.

A multitude of Liszt imitators now flooded the country, cruelly abusing the innocent pianoforte in their vain efforts to show how the master, in whose name they offended, produced orchestral effects on the instrument. They always had a tuner on hand to repair damages, and felt they had done badly if they failed to snap two or three wires of an evening. Sometimes we who heard them were lost in wonder at their bewildering feats; more frequently our finer sensibilities were jarred.

In spite of all disturbing influences, the numbers of those who craved music of high order everywhere increased. In my home city, Philadelphia, chamber music, refined and noble, was enjoyed by ever enlarging numbers. Gifted and thoroughly educated foreign musicians had settled among us as teachers, and were doing noble service in stimulating and cultivating musical taste, and building up a class of earnest music lovers and music students.

THE COMING OF RUBINSTEIN.

At this juncture came Rubinstein—Anton Gregorowitch, the mighty—and revealed to us the hitherto unsuspected resources of the pianoforte. It was in Philadelphia during the season of 1872-3 that I had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of this great Russian tone-colorist, and hear his Titanic interpretations, with their infinitely varied nuances through the medium of the musical instrument usually regarded as cold in comparison with the voice and the violin.

There was nothing cold in Rubinstein’s playing. Its inimitable charm lay in its warmth and beauty of tone, not in its virtuosity, which lacked absolute perfection. Not infrequently, in the white heat of a labyrinth of sounds, he hit some wrong note, but it was quickly forgotten because of the round tonal loveliness surrounding it. The majestic volume of tone he produced won for him the title of the thunderer, yet no one ever displayed more lightness, grace and delicacy than he. A masterly and original control of the damper pedal aided him greatly in controlling the musical rainbow from its most gorgeous coloring to its most delicate tints. In fact, this wonderful matter of the keyboard taught us the force of magnificent touch, tone and technique, illumined by the fire of genius.

AN ENTHUSIASTIC AUDIENCE.

Never to be forgotten by those who were present is a memorable scene at the Philadelphia Academy of Music, when the great Russian presented in superb fashion the Beethoven Sonata in F minor, Op. 57, known most appropriately as the Appasionata, a work written with the heart’s blood of its creator. In response to Rubinstein’s touch, all the fierce conflicts of the soul this noble composition depicts rose clearly before us. We heard the inexorable knocking of Fate, and the wailings of the spectral shadows rising from the depths of the nethermost abyss, relieved by lightning flashes of humor, heard the fervent supplication that lifted the soul into the blue, boundless ether, and the finale that seems to say: “I have fought the good fight—the victory is won.” As the last chord of the concluding presto rang through the building, the usually staid Quaker City audience rose, every man and woman, as by common consent, and gave audible expression to that battle shout of rejoicing freedom, in cries of Bravo! Bravissimo!

Rubinstein’s rendition of the Liszt-Schubert Erl-King was as realistic as that of the sonata. The listener was made to hear the tramp of the horse galloping wildly through the night, like the swift flight of time, or of fancy; the shrill tones of the excited boy ringing through the tempest-laden air; the deep voice of the father, striving to calm his child; the seductive whispers of the elfin beings and the shuddering awe of the dénouement.

One evening, after creating an immense furore with this composition, the great Russian responded to deafening applause with his own transcription of the Turkish March from Beethoven’s Ruins of Athens, then rose from the instrument with an air of resolution. Whirlwinds of enthusiasm brought him out again and again to bow his acknowledgments, but the audience was insistent, demanding more music. His manager, under whose control he chafed, forced him to comply. This I learned later. What was seen at the time was the proud master projected on the stage like a body shot from a cannon’s mouth. Each particular hair of his leonine mane seemed alive, as he seated himself at the piano and struck into the opening measure of Chopin’s Berceuse. But how changed the composition became! For a moment I who was then studying it failed to recognize it, instead of rocking the cradle, the left hand beat the time of a wild barbaric dance, while the right followed with unerring strokes. Only those familiar with this Slavic lullaby can realize what a Herculean task Rubinstein performed in playing it at the speed he took. His manager had worked him up to a pitch of frenzy, and like a giant in chains he gave vent to his fury.

Upon another occasion I heard him direct his Ocean Symphony. At his command was a well-trained orchestra but I had never heard its members play as they played under him. Electricity flowed from his finger-tips, his baton, his presence, forging golden links between himself and the men he held, as it were, in the hollow of his hand. Had I been stone deaf I should have found joy simply in watching Rubinstein conduct.

At the period of the great Russian’s visit to Philadelphia I was struggling heroically through the labyrinths of the Well-Tempered Clavichord of Johann Sebastian Bach. My guide was Carl Gaertner, teacher, violinist, composer and conductor (now deceased), whose life was consecrated to the interests of his art, and whose achievements in the field of musical education have never been fully estimated. He had a keen comprehension of Bach, fully realized the poetry of the works of this master of masters, and had little patience with those who performed them after a stiff, unyielding, pedantic fashion. I was often reminded by him of the statement that a Bach fugue was like a company of polite persons conversing together. Each one knew when to speak, when to be silent, when to differ harmoniously, and when to come together in perfect accord. Moreover, I was compelled by him to commit preludes and fugues to memory, transpose them into various keys, both at the instrument and in writing, and to preserve the freedom, fluency and grace that belong to them.

A VISIT TO RUBINSTEIN.

Mr. Gaertner passed much time with Rubinstein, talked Bach with him, heard him play Bach, became enthusiastic about the Russian’s conception of Bach which fully accorded with his own, and finally mentioned a pupil of his who could show how he taught Bach. The result was an appointment for an interview.

Without preparing me for more than the enjoyment of a personal meeting with the necromancer of the piano who was exercising so inspiring an influence over me, my good teacher ushered me into the presence of the distinguished Russian music-master. We found him in a drawing-room whose main features were a concert grand piano and a quantity of books.

“When I am on a tour I employ my leisure moments in reading great literature,” he said, after welcoming us with the genial cordiality which was one of his marked characteristics. “It is surprising how much that is calculated to broaden the mind may be gained in moments that might otherwise be wasted.”

Here I ventured something in regard to the profit and pleasure I had derived from his concerts.

RUBINSTEIN’S FALSE NOTES.

“May the Lord forgive me for the false notes I dropped!” was his reply, and although he spoke in a half quizzical way, it was evident he took himself seriously to task for any blemishes in his work.

Some question was asked him by my teacher about his touch and tone. Holding up before us his vigorous- looking hands he replied in words akin to those often quoted:

“Look! I have phenomenal fingers, and I have cultivated phenomenal strength and lightness. That is one secret of my touch; the other is assiduous study from youth up. I have sat for hours trying to imitate, in my playing, the timbre of Rubini’s voice, and it is only with labor and tears bitter as death that the true artist is developed. Few realize this. Consequently there are few artists.” Rubini was the famous Italian tenor who first visited St. Petersburg, in 1843.

The conversation turned on the American tour in which Rubinstein was engaged for 215 appearances, and was sometimes obliged to give two programs a day in as many cities. He pronounced it slavery of the worst sort.

THE SLAVERY OF THE CONCERT TOUR.

“One becomes an automaton,” he said, “simply performing mechanical work. No dignity is left the artist —he is lost.”

When asked if it were true that he had rejected an offer of $125,000 to make a second American tour of 50 concerts, more than three times the sum he had received for the present tour of 215, he replied in the affirmative. Nothing could induce him to sell himself again, he said. At the same time, he spoke pleasantly of the musical talent and appreciation he had found in the United States, but persisted that a million dollars would not compensate him for again enduring the managerial bondage, and the fatiguing journeys.

Turning abruptly to me he bade me play for him a Prelude and Fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavichord.

“I play for you, Mr. Rubinstein?” I cried aghast. “No! I could not be so presumptuous.”

“But your teacher has promised me you would play. It interests me to know how he teaches Bach. I expect you to play.”

Controlled by his commanding will I seated myself at the waiting instrument and undertook the G major Prelude and Fugue, in three voices, No. 15, Book I, of the Well-Tempered Clavichord. It was no easy matter to play the composition without notes, under the circumstances. The Prelude is supposed to recall a group of happy children at play, and the Fugue, a joyous dance. I fear the children I evoked gamboled like elephants, and the dance was in wooden clogs. Certainly my recollection is that my fingers seemed weighted with lead, and that I did my very worst rather than my best. Nevertheless the great tone-colorist was gracious and considerate, as he ever was to striving students, and cut short my apologies.

“No—no!” he said, “you have not done so badly. You have shown at least that you have had instilled into you the right idea of Bach. Now I will play that beautiful G major for you.”

RUBINSTEIN’S PLAYING.

With his fond, caressing handling he indeed made the children frolic and sport, and the dancers dance with joyous abandon. Every conceivable nuance of the exquisite melodies was brought out by him with astonishing lightness and elasticity. In the Fugue he assigned to each voice its proper place, giving due prominence to each, in turn, without permitting any to be too assertive.

The helpful hints he gave me by precept and example have always remained with me. He expressed his astonishment that so few pianists have realized the romantic side of Bach, and that especially so many Germans made such dry-as-dust work of the master’s compositions. Reference was made to the art of transposing music at sight and Rubinstein immediately gave us a transcription of the great organ Fugue in B minor which he transposed, with ease, into E flat minor, not missing a note, or omitting an emphasis. More than ever his performance filled me with wonder and admiration. When we parted, I felt that I had gained an influence, in my musical life, that would never cease to endure.

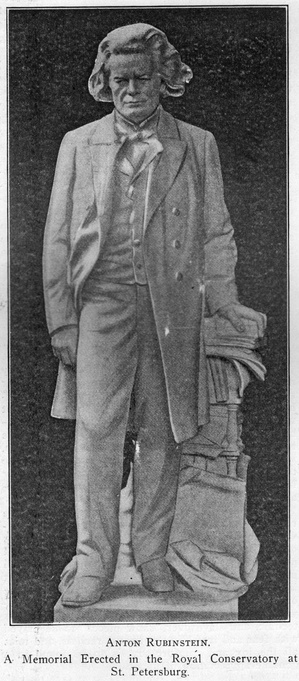

Shortly after Rubinstein’s death, November 20, 1894, I read an account, by a Berlin critic of a visit to the workshop, in the tower of the Peterhof villa, a couple of days after its owner had closed his eyes forever. Here the Russian man of genius had been busy the last day of his life, and his glowing personality still pervaded the room.

RUBINSTEIN’S WORK.

On his writing-table were portraits of those dear to him—his mother, to whom he owed his first musical training; his wife, his children and his brother Nicholas, the sharer of his early musical studies. There was the inkstand he had forgotten to close, the pen he had carelessly thrown down and a pile of manuscript. The grand piano—the medium through which it had been his wont to invest with tone and rhythm his flights of fancy—was open, and on its top was strewn the music he had been looking through during his last working day on earth.

The critic also noted the charming prospect that had been presented to the master from the windows of his work-shop. Owing to the heights on which the villa is situated the view is an extended one. Looking directly over the garden may be seen the River Neva, grandly flowing toward the ocean. To the left lies the mighty fortress of Kronstadt, erected by Peter the Great as a guard to his capital, and to the right is seen the golden dome of St. Isaak’s Cathedral, the oldest and most venerable church in the Czar’s dominion. Grand surroundings for a grand man. As I read, my imagination was kindled, my memories became keenly alive.

So they are whenever I think of Rubinstein, the man and the artist. He is no longer in his workshop—he no longer goes abroad in person to inspire eager piano students, but the influence of his genius and his personality continues to live and bear fruit.