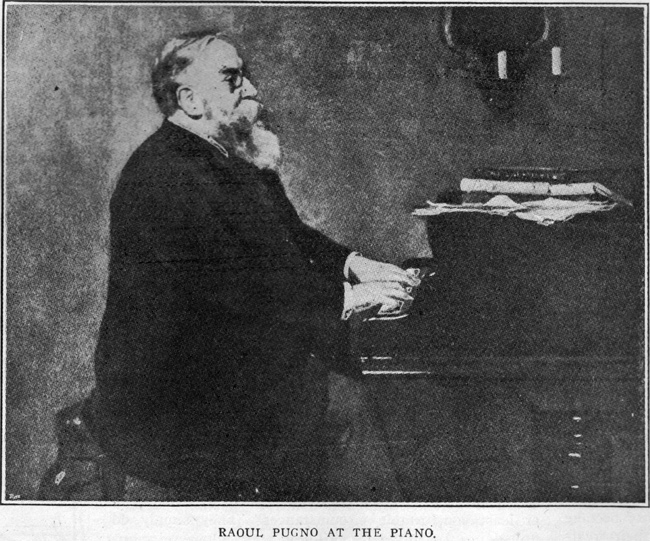

By the Most Renowned of French Piano Virtuosos

RAOUL PUGNO

(Translated Expressly for THE ETUDE by V. J Hill)

(The following article, which first appeared in Europe in Le Courrier Musical, is one of the most sympathetic and illuminating appreciations of the genius of Chopin we have ever seen. Coming as it does from a master of the keyboard who has devoted a large part of his life to the study of the works of the French-Polish composer, it has a special significance for Etude readers.—Editor’s Note.)

There is a period of production in every artist’s life which is in no way governed by his actual age. Corneille did not produce brilliantly until thirty years of age; Mozart was famous at ten, and d’Annunzio at fifteen. Frèdéric Chopin was one of those ardent souls whom a precocity of genius exhausts before their time, and who only seem to hasten to produce because they are mysteriously warned of the shortness of their career. With Chopin, however, this precocity was not accompanied by the kind of feverish excitement so often found in persons of his temperament. On the contrary, his humor was exuberant, lively, jocular, and childlike in its simplicity. He was never observed to be melancholy, but had rather an unusual ardor for loving as well as appreciating the everyday things.

There is a period of production in every artist’s life which is in no way governed by his actual age. Corneille did not produce brilliantly until thirty years of age; Mozart was famous at ten, and d’Annunzio at fifteen. Frèdéric Chopin was one of those ardent souls whom a precocity of genius exhausts before their time, and who only seem to hasten to produce because they are mysteriously warned of the shortness of their career. With Chopin, however, this precocity was not accompanied by the kind of feverish excitement so often found in persons of his temperament. On the contrary, his humor was exuberant, lively, jocular, and childlike in its simplicity. He was never observed to be melancholy, but had rather an unusual ardor for loving as well as appreciating the everyday things.

His love of the country was as profound as filial piety. The nobility of his nature shone forth on every occasion; in the unequalled tenderness—almost a worship—that he bore his mother; in the way in which he loved his friends; in his exalted patriotism; in the sublime ideal he held before him as a musician; in the delicacy and self-respect which always governed his sentimental fervor; and even in the never-failing elegance which so well gave expression to his deep-rooted moral impeccability.

Born amid romanticism, he had little taste for any revolutionary artistic tendencies which savored of bombast and vulgarity. In the sadder moments of his passionate life, in hours when sickness made of him an extremely sensitive being, he never lost a certain chivalric courtesy and aristocratic gentleness. His work never expressed his bitterness, which was intense, except in transforming it, with due reverence for art, into his own language. When alone in his lodgings he improvised freely amid a solitude which enveloped him either as a storm, or as a tender friendship, free to sing, to extol, or to bewail with his awakened voice, his happiness or distress in life. But when he wrote his art was sustained by a firm reticence of style which sternly expressed any inappropriate utterance. Whatever the transports of his lyricism, even the frenzy of certain pages of his bursts of inspiration, he always remains—I do not say master of himself, for he often gives the contrary impression of being carried away by a wind which sweeps him along—but faithful to the superior limitations of the conscience of a great artist.

THE INTIMACY OF CHOPIN’S MUSIC.

For Chopin was a great artist! and if we do not find in him the robustness of Bach, the commanding breadth of Beethoven, or the uniform fertility of invention of Mozart, he seems, at least, to have had the privilege of expressing himself by means of his art with incomparable emotion and sincerity. His charm is of the most striking kind because it is that of grief—of his grief and ours. There is nothing of the aloofness and architectural spirit of the great symphonists; but on the other hand he is much more “intimate.” His music is a melancholy yet sweet collection of love letters, of secret memories, of short poems and confidences, as well able to charm us as to help us look into our own hearts. In listening to Chopin we feel intimately understood, interpreted or judged by the clear-sightedness of an observer accustomed to the landscapes of the heart. When we consider this, we cannot help but feel grateful for this innovator, bold in his simplicity, who was able to reach the noble attainment of opening a new era in music. For we cannot deny that he has opened wide before us the age of subjective and significant music in which to-day we find ourselves.

We must remember that before him the only classic forms known were the sonata, the concerto, variations, and, of course, those light compositions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, joyous or restrained, noble or alluring, tender or sprightly, whose appellations, such as Chacone, Musette, Tambourin, Passepied, Rigaudon, Courante, Gavotte, Minuet, etc., explain that they constituted nothing but elegant pretexts for dancing. Chopin deliberately broke asunder from the last- named charming but superficial forms of production. He was too independent to submit to fixed forms, and if in his Sonata in B flat minor the first part is of decidedly classic form, immediately afterward he relaxes his hold and gives free sway to his genius, providing us in the finale with four sublime pages of poetic fervor wherein he liberates the whirl-wind of the great lyricism by which Chopin at this period lifted himself to Beethovenian heights.

CHOPIN THE INNOVATOR.

Nevertheless, whenever he attempted to use the classic forms he succeeded fairly well. His sonata for piano and violoncello and the trio (for strings and piano) are, however, much less representative of his temperament than the rest of his work. He was more at home in compositions of a nature less distinctly limited, such as Etudes, Preludes, etc.

Until his time, Etudes were but irksome means of acquiring technic. Chopin preserved their incontestable technical utility, but communicated to them such a musical quality that they have become magnificent tone poems of enormous variety, traversing the entire scale of human passions, from the peace ineffable expressed in the Etude in E major to the heroic enthusiasm of that in C minor. As to the Preludes, before his time there were only those of Bach. The Well Tempered Clavichord is a casket which encloses perhaps the only jewels of musical literature capable of containing and summing up in themselves all the divine art of music. They are therefore worthy ancestors of Chopin’s Preludes. And what worthy descendants are his.

What tender charm emanates from the Prelude in D flat major! With what sombre, dramatic mystery the G sharp persists throughout a part of the Prelude! And in that in G minor, how shall we describe the delicious morbidezza of that phrase in the left hand which unfolds itself in such a seductive way. The admirable prelude in E minor is not inferior in lamentation and hidden sorrow to that of Bach in B flat minor. It was while listening to the melancholy theme of the Prelude in A flat, so the story goes, that a great artist, suffering from illness, wished to die, as if that phrase alone would have been, in his failing eyes, worthy of accompanying his last breath. As to the Prelude in C minor it echoes like a sepulchral crypt! But need we cite more? All that music can give of grace, passion, lyricism, dramatic force, beauty, freshness, is found in these pages, which at the same time demand extremely facile, flexible, pianistic technic.

Chopin seemed destined to enlarge the boundaries of the secondary forms of music. Attracted by the charm of certain discoveries, in the realm of folk-song, mazurkas, polonaise, etc. Chopin takes them, animates them, and pours his soul into them; and from these more or less simple dance themes, by remoulding them in the melting-pot of his idealism, he has made veritable masterpieces of grace, style, and exquisite elusiveness.

THE NOCTURNES AND BALLADES.

But it is elsewhere that Chopin proves himself more of an innovator, and still more original. This time he not only renews, he creates. He created the Nocturne and the Ballade. These two forms belong solely to him and may be regarded as the immortal products of his mind. It is in the nocturnes, in fact, that Chopin has most exquisitely expressed the delicacy of his nature, enamored of mystery, sentiment, night, and all-fragrant of that Polish zal which is neither vapid ennui, sulky ill-humor, nor undisguised melancholy, but which retains in its dreamy sentiment a certain quality of hope. Moreover, nearly all the nocturnes are born of the inspiration of love, and of a noble spirit of intimate comradeship. Some, as in the nocturne in F sharp minor, seem to be the outcome of a tender dream, wherein the deep silence is disturbed by a thrill, as of the pressure of a hand, others, such as the 17th, in B major, bring before us soft love-vows breathed in the sweetness of moonlight walks; or yet again, the suave but heartrending meditation of the nocturne in A minor is interrupted by the austere memory of a liturgic chant, heard in some wayside chapel; and in the splendid, majestic nocturne in C minor he seems to find expression for the limit of poignant human suffering. He is therefore the creator of that form of art which has been so frequently imitated since his time, but in which he who had no precursor has had no rival.

No one has since surpassed or even equalled him in the Ballade, of which he was also the creator, and to which he instantly gave his definitive style. The four ballades certainly comprise one of the most important groups of Chopin’s works. Each, in its own different way, portrays a distinct episode; the exalted, overwhelming passion of the first Ballade in G minor is admirably sustained by the insistence of the first five notes, which are reiterated in all their aspect of pride, mystery and resignation; the rich fantasy of the one in F has the fragrance of a springtime flower; the velvet quality of the third, in A flat, is admirably adapted to suit the chosen theme of all devouring tenderness; while the last, in its epic grandeur, is the most touching, the most beautiful, and by far the most personal in its appeal.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF CHOPIN’S MUSIC.

Chopin has also given us an entire series of charming or dramatic compositions, such as the Scherzos, the Impromptus, the Concertos, and his adorable Barcarolle. Important as are his contributions to piano literature, however, his output in the field of orchestral music, vocal music, etc., was somewhat restricted. But it would be difficult to discriminate against him on this account. We need fear in him no mediocrity. Chopin never wrote except when under the influence of an imperative need to give expression to his inspiration, and he has given us only the best of his thoughts. He is an artist who never sought to dazzle by the display of a facile talent; he rather forced his ability to serve his knowledge—somewhat limited as regards the science of music—to externalise his mental state. But whatever be the setting of his compositions, the title by which he designates them, or the character of which they bear the imprint, his music always possesses a uniformity of inspiration which renders it recognisable among any. We feel that all this radiance comes from one same center, the warmth from the same hearth, which is his soul—the soul of a lover, patriot and poet.

Although his music is sometimes subtle, even a little morbid, it nevertheless remains admirable music, whether it is enriched by characteristic harmonies or allowed to die away in elusive cadences; whether it allures us with its charm, saddens us with its profound sorrow, or stirs us with the spirit of a most ravishing csardas; whether we are swept on by the strong rhythms of its wildest caprices, or are uplifted by its dignity and exhortation. Nevertheless, that which is uppermost is the individual, the personal element, which always conveys the intention of uttering, of revealing something, and confiding it to us as to a friend. The consequence, of this intimacy has been a vital development of the art of composing piano music. Before Chopin the piano seemed to have attained the height of its power and means of expression. That prodigious artist and colossal performer, Liszt, had established a fulgurant technic, the immense scope of which had, in a way, compelled the piano to lay aside its usual idiom, and lend itself to a luxuriance of new tone combinations, and to passages of dizzy velocity. Chopin, like Schumann, went further; he profited by this new idiom, but adapted it to the needs of his inspiration. By it he made the piano a multi-colored instrument, the resources of which, it now appeared, had not by any means been exhausted. It was a revelation of new and unsuspected powers.

We cannot truly claim that Chopin’s music contains variety of orchestral timbre. Quite the reverse; his music is always, and solely, piano music, inspired by the piano, and written for the piano. But how much more varied in style! How much richer the colors from his palette than anything offered hitherto (if we except the sonatas of Beethoven)!

THE TECHNICAL DEMANDS OF CHOPIN’S MUSIC.

When playing Chopin, differences of sonority become essential; the tonal effects must be weighed, their treatment studied and modulated like the inflections of the voice. We are led to require of the piano a great many effects not heretofore contemplated; that never before would we have thought of demanding, and which respond to the exigencies of this new musical matter. The originality of his passage-work, the grace, and somewhat odd preciosity of his groups of small notes and appogiaturas, call for a different touch. In a word, it is an entirely new piano school that was initiated by Chopin, which by its sweetness, adaptability, variety, rhythmic combinations, and the independence necessary to the fingers, clearly distinguishes it from Liszt’s school, more encumbered with superfluous notes and often obscured by useless polyphony.

For a long time Chopin was the victim of an unjustifiable reputation as a decadent, effeminate composer, and in the eyes of many generations he passed only as a singer of sickly imaginings and morbid romanticism. He was monopolized by a certain public of cult-faddists from which it is fitting that he should be rescued. Chopin was neither neurotic nor sickly; he was tender, but not weak; refined, but not affected; complex, but not involved; eloquent, but not rhetorical; and his most mournful pages have a distinction which preserves them from decadence. In the background of his music there is always a more or less clear trace of his early high spirits, which is really much more in evidence than melancholy; there is more rhythm than abandonment.

Certain interpretations have mutilated, disfigured and almost eliminated the clearness of his works. That Chopin had an emotional, flexible style of playing is certain, and he preferred to play to women. But this was because he disliked notoriety, and the frequent clamor of men irritated him. Nevertheless, his playing was sane, fervent and passionate. Berlioz reproached him for his too great rhythmic independence. This does not necessarily imply that he was effeminate; and it is rather in response to an exalted sense of accent and phrasing that he varied rhythm, which in consequence became more sensitive, less metronomic, more profoundly musical. We must therefore guard against considering Chopin as an artist imbued with mannerisms and affectation, but rather admire in him the musician of a proud race, who interpreted with rare nobility, delicacy and robust vigor the sweetest sentiments and the most profound passions of the human soul.