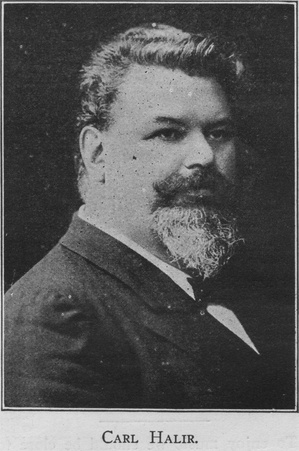

The world of violin playing has sustained the loss of another great violin artist by the death of Carl Halir, the German violinist, whose demise occurred recently at Berlin. Halir occupied a place in the very first rank of German violinists. He was so long associated with Joachim, as a pupil, as a member of the Joachim Quartet, and as a violin teacher in the Hochschule in Berlin, that he possessed all the traditions and ideas of his illustrious master. After Joachim’s death it was considered that his mantle fell upon Halir in the performance of great classical violin works, such as the Beethoven concerto, and the classic string quartets.

Halir was a comparatively young man, only fifty years of age, at the time of his death. He had been ill for some months, and his death, while expected, nevertheless came as a shock to the world of music of Germany. Halir was born at Hohenlebe, in Bohemia, in 1859. His first studies were with Bennewitz, at the Prague Conservatory, after which he completed his studies under Joachim at the Berlin Hochschule. His great talent for violin playing was at once recognized, and he successively held some of the most important positions in Europe as solo violinist and concert master.

His first position as concert master was that with the Bilse Orchestra in Berlin, a position which was also filled at different times by the great violinists, Thomson and Ysaye. At another time he spent two seasons in Italy as solo violinist of the private orchestra of a Russian nobleman.

His first position as concert master was that with the Bilse Orchestra in Berlin, a position which was also filled at different times by the great violinists, Thomson and Ysaye. At another time he spent two seasons in Italy as solo violinist of the private orchestra of a Russian nobleman.

Franz Liszt, the pianist, was a great admirer of the genius of Halir, and through his influence the latter was appointed concert master of the Grand Ducal Court Orchestra at Weimar, where Liszt lived. Halir filled this position with a constantly growing reputation for ten years. He left Weimar in 1894, to become concert master of the Royal Orchestra and teacher in the Hochschule in Berlin, a position he filled until his death.

He played second violin in the Joachim Quartet, and after that master’s death founded his own quartet, which at once took rank as the leading quartet of the German capital. He was also at the head of the foremost Berlin trio, being associated with George Schumann, pianist, and Hugo Dechert, the violoncellist.

HALIR, THE ARTIST.

Halir had a large, splendid tone, unlimited technic, and his readings of the great violin works were noble and authoritative. He was, above all else, a legitimate violinist, and would have cut off his right hand sooner than descend to trickery or charlatanism in his playing. Through his long association with Joachim he imbibed, to a remarkable extent, the ideas and traditions of that master. Halir was a large man, of imposing appearance, over six feet in height, and the violin looked like a toy in his hands.

He had great popularity as a teacher, and trained many pupils who are now eminent, among them being many Americans. Frequent concert tours kept him “on the wing” a great portion of the time. He visited America some years ago, appearing in concert in most of the large cities, and everywhere being hailed as a violinist of great attainments. He had a singularly charming and winning personality, and this power to charm always appeared in his playing. He was remarkably modest and free from conceit. The writer remembers being present during an interview which a young American violin student sought with Halir, during his American tour, for advice as to his future studies. The young man took his violin from the case, and the first thing Halir asked for was a minor scale, then he asked him to play a Kreutzer etude from memory, and finally a few bars of a violin solo. The result being satisfactory, the student expressed a hope that he might one day become a pupil of Halir in Berlin. “I hope you can come to Berlin,” said Halir, “but you do not necessarily have to study with me. You will find twenty-five excellent teachers of the Joachim school of violin playing in Berlin, any one of whom would make an excellent master for you.” Such modesty is in striking contrast with the conceit displayed by so many violinists.

Halir’s compositions were not important, but he wrote some excellent studies for the violin, and his “Scale Studies” should be in the possession of every violinist.