With the organ, as in the orchestra, precision must rule; the perfect ensemble of feet and hands is absolutely necessary, whether in attacking or leaving the keyboard. All notes placed in the same perpendicular by the composer must be made to speak and to cease speaking at the same time, obedient to the baton of a single conductor. Here and there are still seen unfortunates who suffer their feet to trail along the pedals, and who forget them and leave them there, although the piece is long since finished. It reminds us of the old viola player at the opera, who regularly went to sleep during the fourth act, to be charitably wakened by his comrades at the end of the evening. It was a tradition. But one fine day the management changed hands; tradition had to change, too, and it was forbidden to awaken the sleeper. They were giving “The Prophet.” Neither the crash of the introduction, the collapse of the palace blown up with dynamite, the din of the orchestra, nor the tumult of players and audience leaving the theatre could cut short his dreams. When he finally opened his eyes in the profound darkness, he believed himself, like Orpheus, in the infernal regions, and on attempting to make his exit pitched head-foremost into the kettledrums, which collapsed. The next day his eligibility for retirement was recognized.

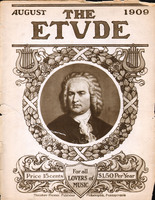

I should like to know what an orchestral conductor would say, after having given the last stroke of his baton, if his third trombone player should permit himself tranquilly to continue to prolong his note? From what savage cave can such a barbarous custom have emerged? Yet some years ago it was a generally prevailing fashion, a veritable epidemic.—From the Preface of “Johann Sebastian Bach, the Organist” by Ch. M. Widor.