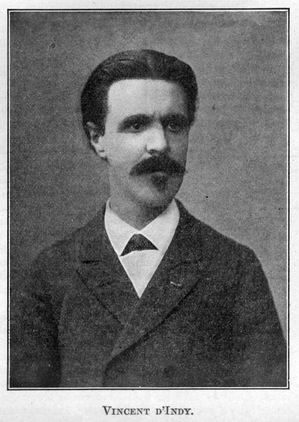

In spite of the amazing versatility of Saint-Saëns, and the graceful fertility of Massenet, it is toward the so-called “younger school” of French composers that the eyes of the musical world are turned today. Among a group of such diverse types as Alfred Bruneau, Gustave Charpentier, Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas and Gabriel Fauré, besides the more unfamiliar names of A. de Castillion, P. de Breville, Henri Duparc, Charles Bordes and others, Vincent d’Indy stands out clearly as the leader, not only by sheer force of personality, but by the artistic quality of his varied achievements.

In spite of the amazing versatility of Saint-Saëns, and the graceful fertility of Massenet, it is toward the so-called “younger school” of French composers that the eyes of the musical world are turned today. Among a group of such diverse types as Alfred Bruneau, Gustave Charpentier, Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas and Gabriel Fauré, besides the more unfamiliar names of A. de Castillion, P. de Breville, Henri Duparc, Charles Bordes and others, Vincent d’Indy stands out clearly as the leader, not only by sheer force of personality, but by the artistic quality of his varied achievements.Vincent d’Indy was born at Paris, March 27, 1852. His family is aristocratic and wealthy; his father was an amateur violinist and was fond of music. D’Indy was brought up by his grandmother, Madame Theodore d’Indy, and it is due to her cultivated influence that his musical tastes were formed on serious lines. At the age of ten, he began piano lessons with Dièmer and harmony with Lavignac, both professors at the Paris Conservatory. These lessons lasted until 1865. At fifteen, d’Indy became acquainted with Berlioz’s instrumentation, and two years later he came to know Wagner’s scores under the guidance of Henri Duparc, a pupil of César Franck. Then came the Franco-Prussian war, in which d’Indy served as a volunteer in the 105th regiment of infantry. For several years he had been studying law in a desultory fashion, out of deference to his family, but after the war he renounced the law for a musical career.

In 1872, he became a pupil of Cesar Franck, both at the Paris Conservatory and as a private pupil, and thus laid the solid foundations of his unusual grasp of the technic of composition. In 1873, he made musical pilgrimages to Brahms and Liszt, and was even a pupil of the latter for a time. During several years following, d’Indy served in various practical capacities as second drummer and chorus leader of the Colonne concerts, and as chorus leader of the Lamoureux concerts. In 1885, d’Indy won the prize offered by the city of Paris with “The Song of the Bell,” after Schiller, the text by d’Indy himself, for solos, chorus and orchestra. D’Indy was one of the founders of the National Society of Music, and after Franck’s death in 1890, he became its president. In 1895, he was offered a professorship at the Paris Conservatory, which he refused. In 1896, he founded, with Charles Bordes, the conductor of the famous choir “The Singers of St. Gervais,” and Alexander Guilmant, the celebrated organist, a school of music on new lines, the Schola Cantorum not, as some have believed, for a capella singing, but providing a thorough education in all branches of music. Its standards are broad and helpful, it wishes to produce true artists and not mere acrobats who juggle with technic. The Schola has been exceedingly successful; it is responsible for a considerable development in the direction of modern music at Paris. Moreover, it gives remarkable concerts, chiefly programs of little-known music, including operas by Monteverde, Rameau and Gluck, church cantatas and oratorios by Bach, etc. D’Indy has published the first volume of a treatise on composition, with a new and striking plan; his treatment of the subject and the novel exposition of ideas show at once the extent of his erudition and his unusual capacity as a teacher. He has also contributed not a little to a fuller comprehension of César Franck’s artistic purposes and work as a teacher, by various sympathetic articles.

At present, d’Indy divides his activity between composition and the Schola Cantorum. He has occasionally acted as conductor, and it is in this capacity that he is visiting the United States to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra in programs of music by Franck, Chausson, Fauré, Dukas, Debussy and himself, although he will perform in some of his chamber-music.

D’Indy has attempted all forms of composition, but it is as a dramatic composer that he reaches the highest level. Hence, his greatest works are his operas “Fervaal” (1889-95) and “The Stranger” (1898-1902), and portions of his early work “The Song of the Bell” (1883-85). “Fervaal,” although obviously modelled on Wagnerian lines, is, nevertheless, strongly individual, most characteristically French, and marvelous in its poignant emotion and intense dramatic expression. “The Stranger” is a more compact work, more concise in style and economical in resource. It shows virtually no Wagnerian influence, and while there are some extraordinarily dramatic scenes, it is not so remarkable a contribution to French opera. Close in rank to the dramatic music are his two symphonies, Op. 25, No. 1, “On a Mountain Air” (with the piano as an orchestral instrument) and No. 2, in B-flat, Op. 57 (d’Indy has renounced an early symphony, Op. 5, entitled, “Jean Hunyade”), a set of symphonic variations, “Istar,” which are all skilful in construction, striking in thematic treatment and brilliant in orchestration, besides displaying individual poetic and artistic qualities. Other orchestral works by d’Indy worthy of especial mention are his early ” Wallenstein” Trilogy, Op. 12, after Schiller; “Songe Fleurie,” Op. 21, a “legend,” a Fantasie, Op. 31, for oboe and orchestra, “on popular themes”; a suite, Op. 47, arranged from incidental music to Catulle Mendes’ drama “Medeée,” and a Varied Choral for saxophone and orchestra, Op. 55. A still earlier work, “The Enchanted Forest,” after Uhland, is not so individual, resembling similar works by César Franck. D’Indy’s latest work for orchestra is entitled, “Summer Hours on the Mountain,” in three parts: “Sunrise,” “Afternoon” and “Evening.” In consummate mastery of the orchestra, d’Indy is second only to Richard Strauss.

Next in importance is his chamber-music. Including an early piano quartet, he has written two string quartets, Op. 35 and 45, a trio for piano, clarinet and ‘cello, Op. 29, “Songs and Dances” for wind instruments, Op. 50, and a suite in the old style for trumpet, two flutes and strings. These are all original in form, well-written for the instruments, and containing notable beauties. His piano music is not voluminous, the best-known are “Poem of the Mountains,” Op. 15, and “Tableaux de Voyage,” Op. 33. There are also three Romances, Op. 1, a Sonatina, Op. 9, four pieces, Op. 16, three waltzes, Op. 17, a Nocturne, Op. 26, and a Promenade, Op. 27. On the whole, d’Indy’s piano music is less individual than his contributions in other departments. He has also written seven or eight songs, of which his “Lied Maritime” is the most striking. Other compositions worthy of mention are the ballade “La Chevauchée du Cid,” Op. 11, for baritone, chorus and orchestra, a “Lied” for ‘cello and orchestra, Op. 19, a beautiful chorus for women’s voices and piano accompaniment, for which d’Indy wrote the text. There are also motets, canticles, a church cantata, etc.

D’Indy’s principles as an artist are developed from the teachings of César Franck, of whom he was the ardent disciple, not only as a teacher of composition, but as an artist and as a man. D’Indy’s attitude is that of a self-denying apostle. His chief object is to serve music in the deepest sense. To his high aims as a composer he unites an extreme obligation to give aid in every way to those who desire to learn. Rich himself, he devotes himself unselfishly and unsparingly to spreading the gospel of music as taught him by Franck. It is too soon even to predict d’Indy’s ultimate rank as a composer. In mastery of technic, in vividness of expression, he stands very high; his originality and power are incontestable, while his reverent devotion to the memory of Cesar Franck by word and deed is without parellel (sic) in this self-seeking age.