If this could be proven; if, as many of the most sensitive and critical musical observers believe, each separate major key has its own peculiar mood or atmosphere, then we might point to still another, and probably the best and most convincing answer to the question: Why is music written in so many keys? But an “opinion” cannot be admitted as proof, not even when it emanates from sensitive and critical observers; much less a mere prejudice, based possibly upon indefensible personal impressions or easily misinterpreted outward signs.

The question may be reduced, I think, to the following tangible form: Are the keys separate personal entities, like the individual members of a social or family group; or are they merely exactly identical numerical quantities, like successive telegraph poles, or the impassive columns on the front of a temple? Still more pointedly: Is a key a person or an object? The latter condition would seem to be borne out by an impartial scrutiny of the technical foundation of a key; and, by the way, it is the major form to which the discussion must be confined; it is “key,” not “mode,” that we are considering.

A key, as it is called (or tone-family, as it perhaps should be called), consists in an accurately definable complex of related tones, selected from the realm of tone by a certain rational (scientifically demonstrable) and never-varying method. It has its keynote; its dominant, a perfect fifth above, and its subdominant a perfect fifth below, the keynote; it has its second, sixth, third, and seventh scale-steps, defined in successive higher perfect fifths above its dominant; in a word, it is composed of contiguous perfect fifths.

The perfect fifth is an absolutely fixed quantity, never differing by a shade of vibration in the old true scale, nor differing from its artificially modified ratio in the modern “equalized temperament.” Therefore, whether equalized or not, the physical consistency of each and every major key must be absolutely identical. In changing our key-basis we simply shift this complex of conditions to another place in the tone-realm, just as a car may be shoved back or forth to different points of its road without undergoing any alteration in size, shape, or material.

The first conclusion that thrusts itself upon us is that there cannot possibly be any difference between one major key and any other; and, of course, there cannot be, as far as the technical form, the internal economy of the key, is concerned; and the distinction between, say C major and G major, is one of location.

But a change, even in location only, is a change; and this may be sufficient to distinguish the keys externally from each other, and give rise to a semblance of individuality. The self-same car, shifted to different points of its track, will appear larger or smaller to the stationary observer, according to its location with reference to his point of view. The change of location, among keys, is not definable by the same system of mensuration involved in the movements of the car, but by a no less accurate system of numerical comparison.

A key is the amplification of a single tone (its keynote); and the physical property of a tone is the type of that of its whole key. A tone is the result of a certain steady vibratory action; being steady, its velocity is exactly definable by a number; hence, the physical property of tone is denoted by a number,—the numerical index of its vibratory velocity. The “middle A” of the pianoforte keyboard is labeled 440,1 that being the number of vibrations per second which create the sensation of that particular tone within the chamber of the hearing ear. The E below it is labeled 330. And so on, every conceivable tone having its number, and, consequently, every key its particular degree of vibratory activity.

Some music-lovers can distinguish these varying rates of velocity so accurately that they know which tone is sounding, without reference to the keyboard or comparison with other, previously defined tones. Not all persons, however,—in fact, not many,—possess this ability of defining the absolute pitch of tones; and it might therefore be concluded that any individuality of key that is based upon this distinction would be recognizable only by the very small minority of music-lovers who are thus able to define the pitch of a tone. But that proves nothing; the distinction does surely exist, whether few or many are immediately conscious of it and able to define it.

This, it must be remembered, is the only actual distinction between one key and another, in that of varying acuteness of pitch, arising from different grades of vibratory velocity. And while it must be admitted that it does constitute a real difference, it also proves that whatever “individuality” or “mood” may result from this distinction is not a matter of guesswork, but wholly a matter of comparison, and definable with mathematic accuracy. It is a definite, fixed, incontestable qualification, not to be confunded for an instant with the fanciful definitions of “key-mood” given from time to time by musical writers, varying with characteristic indecision, but agreeing in precisely those details which prove the assertion I have made.

The mathematic definition of the distinction in question is demonstrated as follows:—

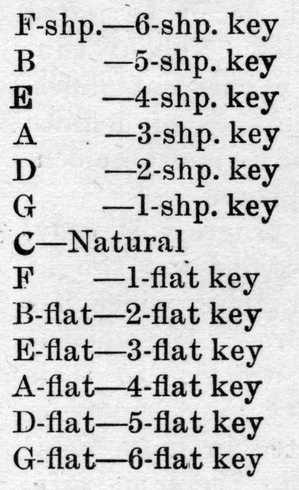

The related keys, as every music student knows, lie a perfect fifth apart, precisely as do the single tones (which become their keynotes) in the great chain of tone-affinities,—illustrated in its correct vertical form in the table. Calling the perfect fifth a “degree,” we say that the whole system of keys represents successive degrees of tone-affinity, stretching upward from the key of C (the natural scale), from one sharp-key on to the next, and downward from C through the flat-keys; or, rather, reaching upward and downward through the whole column of keys, without regard to C, or any other tone, as special starting point. And, as the degrees are thus numbered by key-signature (like the floors of a building), the distance and direction from a given key to any other may be quickly discovered by simply comparing their signatures. From F (one flat, or one degree below zero) to A-flat (four flats) is a distance of three degrees downward; from D (two sharps, or two degrees above zero) to F-sharp (six sharps) there is a rise of four degrees.

The related keys, as every music student knows, lie a perfect fifth apart, precisely as do the single tones (which become their keynotes) in the great chain of tone-affinities,—illustrated in its correct vertical form in the table. Calling the perfect fifth a “degree,” we say that the whole system of keys represents successive degrees of tone-affinity, stretching upward from the key of C (the natural scale), from one sharp-key on to the next, and downward from C through the flat-keys; or, rather, reaching upward and downward through the whole column of keys, without regard to C, or any other tone, as special starting point. And, as the degrees are thus numbered by key-signature (like the floors of a building), the distance and direction from a given key to any other may be quickly discovered by simply comparing their signatures. From F (one flat, or one degree below zero) to A-flat (four flats) is a distance of three degrees downward; from D (two sharps, or two degrees above zero) to F-sharp (six sharps) there is a rise of four degrees.

Now, what is called the rising or falling of tone is respectively an increase or decrease of vibratory velocity. A “higher” tone results from a higher rate of vibratory speed; the effect of ascent is that of greater tension; of descent, greater relaxation. In rising from C to G we increase the tension; and in returning from G to C the tension is removed.

Here, then, we discern a perfectly definite, palpable, physical distinction that assuredly differentiates the keys; and it does so through a sensuous quality that is grasped and measured by our nervous system, which quickly responds to every variation of tension or relaxation. For this very reason the distinction may perhaps justly be interpreted as the “mood,” or “individuality,” of the key. G major (one sharp) possesses a condition of vibratory tension that is one degree (let us continue to use the term) greater, or higher, than that of C major; and one degree less, or lower, than that of D (two sharps). In passing from C to G—an ascending degree—our pulses quicken a little; we have a sensation of increasing tension, brightness, exhilaration; in passing on upward from G into D, the sensation is repeated and doubled. In passing from G to C—a descending degree—we experience corresponding relaxation, a sensation of dullness, somberness.

But is this physical property of each key sufficiently definite, in and by itself, to induce the composer to reduce his choice to one certain key? Is it not rather a relative than a specific quality—a matter of comparison? Observe that G major when in company with C aroused a sense of increased tension; but in company with D the same key brought a feeling of relaxation.

One deduction is certain; and it is the one general distinction in which all fanciful interpretations of “mood” concur; namely, that the sharp-keys are brighter, more tense,—and the flat-keys duller, more subdued, in affect. And these opposite effects, increasing or decreasing in exactly equal proportion as we ascend or descend the great chain of signatures, are most pronounced in the keys with the largest number of sharps or flats; six sharps is the brightest of the keys commonly employed, and six flats the dullest. Upon the piano or organ, because of their equalized temperament (whereby the actual difference between F-sharp and G-flat is removed), this extreme distinction of brightest and dullest key is naturally lost; and that suggests the conclusion that possibly all other supposed distinctions may be lost with it. In my opinion it does modify, but cannot wholly destroy, the sensations of increased or decreased tension, because their physical existence is absolutely indisputable. In the orchestra, and in unaccompanied vocal pieces, the distinction is apt to be more accurate, and therefore more emphatic.

Another point that must not be overlooked is the fact that a similar alteration of vibratory velocity takes place within the same key when it is shifted one or more octaves to a higher or lower register. Consequently there is greater tension in G major when played on the upper part of the keyboard than when played lower. But the change in velocity from one register to the octave above is a precise duplication of speed, and that is so simple a ratio that it does not affect the quality of the sensuous impression, but its quantity only. Hence, G major will represent the same quality of increased tension or brightness, as compared with C major; it will simply be more—or less—distinct.

* * *

So much for the physical properties actually inherent in the keys themselves. The final question is: Whether these are sufficient, in themselves, to create individual “mood,” or whether the “moods” associated with various keys are not (1) largely imaginary, (2) based upon comparison, (3) based upon personal association of impressions, or (4) due to wholly external and arbitrary circumstances, is nowise tenable as inherent in the key itself?

A large array of indications and even facts seems to argue in favor of the latter assumption.

In the first place, unless it can be proven that a certain key (say, C major) possesses exactly the same individual character in the judgment of every critical musical observer,—if opinion differs in the least, or if the supposed character is not instantly replaced by another “mood” when the instrument (without the player’s knowledge) chances to be tuned a quarter tone or so higher or lower than the expected common pitch,—then we must conclude that the impression is an imaginary one. The same conclusion is forced upon us if the observer does not associate the assumed “mood” with a certain key in every piece (whatever its character or style may be) that is written in that key; for if the style of the piece influences the mood, then it is the quality of the piece, and not the inherent individuality of the key, which creates the impression.

Second, the force of comparative impressions has already been touched upon. Unquestionably, C major will sound brilliant if it appears abruptly after some distant flat-key (say, A-flat); but will sound somber if taken in the same manner after a distant sharp-key (say, E). This, I know, does not disprove the independent vibratory degree peculiar to C, but it implies how great a portion of the supposititious “mood” of a key may be due to comparison with other keys.

Third, it is quite probable that, after hearing a certain composition several times in its particular key, the least observant of us would notice the effect of its transposition into a different key; and quite probable, too, that the change, in effect, would be attributed to the “moods” of the keys, whereas it is actually the character or mood of the piece disturbed by change of association. If it be a vocal composition, the text (with its vastly greater distinctness of mood) will infuse its atmosphere into the music, imparting to it a character easily mistaken for its own. Our impression of a key may, I believe, be influenced by other, purely personal, associations.

Fourth, the influence of external conditions upon the character of certain keys is a very real and unmistakable factor. On the stringed instruments of the orchestra (and in violin music generally) the keys of G, D, and A sound more sonorous than the others, because of the frequency of the open strings, with their rich, free tone, upon the dominating scale- steps. And, similarly, the flat-keys are richer in the brass instruments because of the greater prevalence of open tones. Keys which require almost constant “fingering” are certain to convey a more cramped, constrained impression, than those for which the accidental mechanical formation of the instrument is better adapted. The same conclusion is reached from a purely technical standpoint; some keys are much more convenient to finger than others, and the bright, inspiriting freedom of expression which naturally attends ease of execution is proportionately furthered or hampered. In the same sense, a judicious choice and use of compass and register—be it of instrument or of voice—must conduce to freedom of utterance and brightness of mood; hence, it is possible that the composer, in his choice of key, could be governed by no more rational impulse than that of careful adjustment of the means to the end.

Summing up the testimony, it appears hard to believe that a major key has any peculiar individual essence which distinguishes it inherently from its major fellows; and altogether probable that the so-called “mood” of a key is (to a great extent, at least) either an imaginary or an arbitrary attribute for which the fancy of the person, or some external condition quite apart from the key, is responsible.

* * *

About minor little need be said. The minor mode is a bent form of the major scale, as those familiar with its demonstration in my harmony books will probably concede. And this artificial deflection from the major form infuses a stronger dissonant flavor into the mode, giving it a very decided character of its own, wholly distinct from major. So great is the distinction, that the choice between major and minor is instantly determined by the composer, solely, I am sure, upon the basis of mood or atmosphere. But it is here, again, very probable that, like the majors inter se, the minors are all alike,—excepting in quality of vibratory tension.

1The so-called “International Pitch,” very much used, gives A 435 vibrations per second.